Sri Lankan Domestic Migrant Workers (International Labour Organization-Maiilard J)Historically, humans have left their homes to build a different, hopefully better, existence somewhere else. People break away from their countries of origin for several reasons, including lack of economic opportunities, social inequality, poverty, political repression, persecution, warfare, and natural disasters.[1] In 2016, more than 247 million people, or 3.4 percent of the world population, lived outside their countries of birth. There are different legal terms to categorize persons who move across an international border, such as migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. This article focuses on migrant women, who leave their country of origin in search of work and better economic opportunities. Many migrant women are invisible players in the global economy and often suffer from human and labor rights violations. The proposed policy recommendations aim to improve migrant women’s living and working conditions.

The feminization of migration is a multidimensional phenomenon. First, women are on the move as never before in history.[2] In 2015, women comprised 48 percent of all international migrants worldwide. Second, there is a growing demand for migrant women’s labor in destination countries, especially in the care, domestic, and manufacturing sectors. Millions of women from the Global South are migrating to do “women’s work” that women in the Global North are no longer able or willing to do.[3] Third, women have become independent migrants and/or primary economic providers.[4] Currently, fewer women move for family reunification and more move in search for jobs as nannies, nurses, maids, or sex workers.[5] Women moved $300.6 billion dollars in 2016, equivalent to half of the world remittances. This means that women move as much money as men, but at a greater percentage of their income, since they usually earn lower wages.

Causes of the Feminization of Migration

Since the 1980s, the global economy has undergone a series of changes that have led to the feminization of migration. First, structural adjustment programs in the Global South led to major cuts in social spending and the privatization of public services, such as education and healthcare. Neoliberal policies have been materializing in the Global South in the form of higher poverty levels, social inequalities, unemployment, and informal economies. Studies show that when men have trouble as economic providers, women enter the workforce to support their families.[6] Women in the Global South often choose to migrate because economic pressures compel them to.[7]

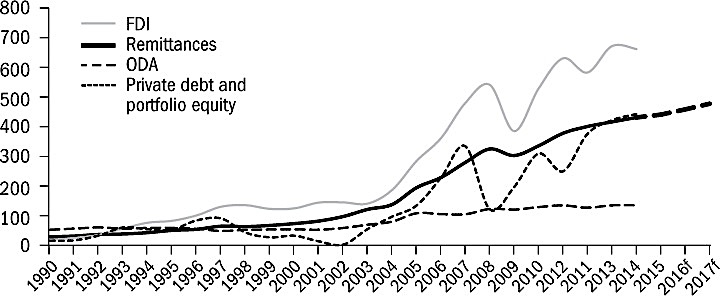

Second, global inequalities in wages are particularly conspicuous. For instance, in Mexico the daily minimum wage per day is approximately $4.00, while in New York State the hourly minimum wage is $9.70. Castles and Miller write that “migration has become a private solution to a public problem.”[8] One way to close the gap between rich and poor countries is to close it privately, by moving to a country with higher wages.[9] Migration has emerged as a solution not only for individuals and families, but also for governments: remittances[10] have great potential to contribute to the development of countries. Remittances are a source of income that goes directly to households, stimulating the local economy.[11] In 2015, worldwide remittance flows are estimated to have exceeded $601 billion. Of this amount, developing countries received about $441 billion, nearly three times the amount of official development aid, and even bigger than foreign direct investment inflows once China is excluded.[12]

Third, with the decline of the welfare state, countries in the Global North are also experiencing changes in their traditional family-based model of care. The insertion of women into the workforce, paired with the aging of the population, have caused a disruption in the provision of care for children, elderly, sick people, and people with disabilities.[13] One of the most accessible options for middle and high-income households in the Global North has been to hire a domestic worker to provide care services, who often is a migrant herself who has left her own children under the care of another woman.[14] This process, in which responsibility for the labor of care-giving passes from one woman to another, is known as the global care chain.[15] The growing “care industry” is creating an enormous demand for migrant women’s labor.[16]

Fourth, the world has been experiencing structural economic changes, including the out-shoring and out-sourcing of production to reduce costs. Manufacturing industries worldwide are based on a flexible and cheap labor force. In “Bananas, Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics,” Cynthia Enloe explains the process by which some manufacturing industries have been feminized, including garments, food processing, cigarettes, and textiles. Factory managers in these industries prefer to hire women over men, because of gender stereotypes that make women “ideal candidates” for manufacturing jobs: women are believed to be compliant, hardworking, and docile; women are assumed not to need a family wage because their incomes are supplemental for a household; women are seen as “natural” sewers; women do not organize unions; and women are a replaceable commodity.[17] As a result, there has been an upsurge in the demand for migrant women’s labor, and that labor is then directed into poorly paid economic sectors where women often face deplorable working conditions and few legal protections.[18] In origin countries, gender inequalities and discrimination are also important drivers of women’s migration. Families choose to send a female family member abroad due to the idealized conception of women as more likely to sacrifice their own well-being for that of their family. Other women migrate to escape domestic violence, unhappy marriages, or pressure to marry.[19]

Fifth, some countries, like the Philippines and Sri Lanka, have created special bureaus to actively promote the migration of women. For instance, the Sri Lanka government has pre-departure training programs to teach women how to handle domestic appliances, prepare food, and arrange a table. The Philippine government has signed more than 25 bilateral agreements on health services and human resource cooperation to export healthcare providers. The Philippines is the center of a large nursing education sector and is thus an important supplier of nurses worldwide.[20]

Consequences of the Feminization of Migration

Migrant women workers, especially undocumented ones, often suffer pervasive violations of their human and labor rights. In the United States, victims of trafficking are almost exclusively immigrants, and mostly immigrant women. Immigrant women are particularly vulnerable to human trafficking because of their lower levels of education, inability to speak the language, and lack of familiarity with employment protections.[21] Furthermore, immigrant women are frequently isolated in private households, without papers or legal protection. They work long-hours for low wages and their work can be particularly degrading. Many of them are victims of psychological, physical, and sexual abuse.[22]

Generally, migrant women cannot bring their children with them. These women give to children in the Global North the love they cannot give to their own children.[23] Arlie Hochschild, in her article “The Nanny Chain,” asks: “Is the Beverly Hills child getting “surplus” love, the way immigrant farm workers give us surplus labor? Are first world countries such as the United States importing maternal love as they have imported copper, zinc, gold, and other ores from third world countries in the past?”

Millions of children in the Global South have been left behind by their mothers. For instance, there are an estimated 9 million Philippine children with one or both parents working overseas as a labor migrant. The question is: how are these children doing? Research is not conclusive, but a study in Moldova and Ukraine showed that the absence of a parent can be detrimental to a child’s social and psychological development. Left-behind children tend to face problems related to school, health, addictions, and delinquency.[24]

The care-drain affects not only the left-behind children but also entire countries, like the Philippines, where nurses are encouraged to migrate elsewhere despite the country’s weak domestic health care system. Nurses in the Philippines are supported by their government to become global care providers instead of domestic care providers, implicating them in development more as sources of remittances than as potential contributors to the national health care system.[25]

Policy Recommendations at the International Level

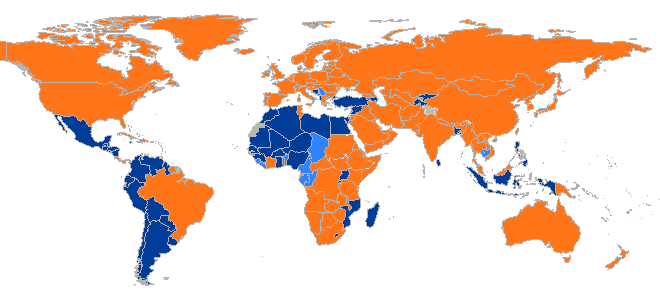

A strategy that countries could pursue to improve migrant women’s living and working conditions is to ratify the existing treaties aimed at protecting their rights. The International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (hereafter also referred to as the Migrant Worker Convention), adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1990, is the world’s only comprehensive document for the protection of migrant workers.[26] The Migrant Worker Convention guarantees fundamental rights for all migrants—both documented and undocumented—including the right to effective protection by the State, to receive assistance of consular authorities, to a fair hearing, to emergency medical care, to overtime pay, and to not be held in slavery or servitude. Only 50 countries are State Parties to the Convention, to date; an additional 16 are signatories, and 132, including the United States, have taken no action.

Other international instruments that protect the rights of migrants are the Domestic Workers Convention (No. 189) and Domestic Workers Recommendation (No. 201) of 2011, which contain provisions to address the particular needs and risks faced by migrant domestic workers. The Convention and Recommendation seek to guarantee minimum labor protections to domestic workers, including the freedom of association, the right to collective bargaining, the right to decent living and working conditions, the right to keep their travel and identity documents, the right to overtime compensation and periods of rest, minimum wage coverage, and the right to paid annual leave in accordance with national laws. The Convention also requires that migrant domestic workers be informed of their terms and conditions of employment, preferably through written contracts. These international instruments are relevant to protect migrant women who work in the domestic and care sectors. Nonetheless, the Domestic Workers Convention has only 23 State Parties, and the United States is not one.

Policy Recommendations at the National Level

Governments could also offset the effects of the feminization of migration at the national level. First, countries of origin that face brain-drains could seek ways to create domestic job opportunities thereby reducing women’s need to migrate. Why, for example, does the Philippines invest in exporting their nurses instead of investing in the domestic health care sector to employ them? Investing in the local economy—including education, infrastructure, hospitals, and public services—rather than in special bureaus to promote the migration of women, will reduce the care- and brain-drain in the Global South.

In addition, governments must revise the model whereby most professional careers are still based on work schedules designed for an independent worker without care responsibilities, a model that assumes that full time workers with children will be partnered with full time caretakers for those children.[27] Governments worldwide should promote domestic laws that guarantee and regulate the rights to maternity and paternity pay and leave, to public childcare, to after-school programs, to a flexible work schedule, and to home offices. Such laws will not only allow working mothers to take care of their children, but they will also encourage working fathers to get involved in domestic and care work. The creation of laws that protect and raise the value of care will reduce both the care deficit in the Global North and the global demand for migrant women’s labor.

Finally, for those women who still choose to migrate, governments should create laws like the Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights of New York State that gives domestic workers—both documented and undocumented—the right to receive at least the minimum wage, overtime pay, a day of rest every week, three paid days of rest each year, protection under New York State Human Rights Law, and a special cause of action if they suffer sexual or racial harassment. Enacting laws aimed at protecting domestic workers will improve migrant women’s working and living conditions.

To conclude, it must be underscored that the feminization of migration is not necessarily problematic. It could even be argued that the fact that women in the Global North are more able to pursue full-time professional careers while other women perform paid domestic and care work is an advantageous situation. Under this model, however, migrant women are being pushed to migrate in search of better opportunities, and do so with few or no legal protections. The invisibility of the feminization of migration is putting women at risk of being abused, exploited, or trafficked at countries of origin, transit, and destination. Thus, it is necessary to implement specific policies to protect the rights of migrant women, including their right to have a family, to physical integrity, to decent working conditions, to fair wages, to education, to healthcare, and to equal access to justice.

References:

- Barbara Ehrenreich and Arlie Russell Hochschild, Global Woman: Nannies, Maids, and Sex Workers in the New Economy, 1st Owl Books ed. (New York: Metropolitan/Owl Books, 2004), 8, http://newcatalog.library.cornell.edu/catalog/6069349. ↑

- Ibid., 2. ↑

- Ibid., 3. ↑

- Allison Petrozziello, “Gender on the Move: Working on the Migration-Development Nexus from a Gender Perspective” (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: UN Women Training Centre, 2013), 52, http://www2.unwomen.org/-/media/field%20office%20eca/attachments/publications/2013/unwomenl_migrationmanual_low4.pdf?vs=1502. ↑

- Ehrenreich and Hochschild, Global Woman, 20. ↑

- Petrozziello, “Gender on the Move: Working on the Migration-Development Nexus from a Gender Perspective,” 40. ↑

- Ehrenreich and Hochschild, Global Woman, 27. ↑

- Stephen. Castles and Mark J. Miller, The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World, 4th ed., Rev. & updated. (New York: Guilford Press, 2009), http://newcatalog.library.cornell.edu/catalog/6406738. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- “Remittances” are funds or other assets that migrants send to their home countries. ↑

- Petrozziello, “Gender on the Move: Working on the Migration-Development Nexus from a Gender Perspective,” 20. ↑

- Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD), “Migration and Remittances Factbook 2016. Third Edition” (The World Bank Group, 2016), http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPROSPECTS/Resources/334934-1199807908806/4549025-1450455807487/Factbookpart1.pdf. ↑

- Petrozziello, “Gender on the Move: Working on the Migration-Development Nexus from a Gender Perspective,” 40. ↑

- Ehrenreich and Hochschild, Global Woman. ↑

- Petrozziello, “Gender on the Move: Working on the Migration-Development Nexus from a Gender Perspective,” 40. ↑

- Ehrenreich and Hochschild, Global Woman, 20. ↑

- Cynthia H. Enloe, “‘Women’s Labor Is Never Cheap. Gendering Global Blue Jeans and Bankers,’” in Bananas, Beaches and Bases : Making Feminist Sense of International Politics, Second edition. (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2014), http://newcatalog.library.cornell.edu/catalog/8634096. ↑

- Petrozziello, “Gender on the Move: Working on the Migration-Development Nexus from a Gender Perspective,” 40. ↑

- Ibid., 42. ↑

- Leah E. Masselink and Shoou-Yih Daniel Lee, “Government Officials’ Representation of Nurses and Migration in the Philippines,” Health Policy and Planning 28, no. 1 (January 1, 2013): 90, doi:10.1093/heapol/czs028. ↑

- American Civil Liberties Union, accessed January 25, 2017, https://www.aclu.org/other/human-trafficking-modern-enslavement-immigrant-women-united-states. ↑

- Ehrenreich and Hochschild, Global Woman, 107. ↑

- Arlie Rusell Hochschild, “The Nanny Chain,” The American Prospect, December 19, 2001, http://prospect.org/article/nanny-chain. ↑

- Ehrenreich and Hochschild, Global Woman, 22. ↑

- Masselink and Lee, “Government Officials’ Representation of Nurses and Migration in the Philippines,” 90. ↑

- Beth Lyon, “The Unsigned United Nations Migrant Worker Rights Convention: An Overlooked Opportunity to Change the Brown Collar Migration Paradigm,” New York University Journal of International Law and Politics 42 (2010 2009): 397. ↑

- Catherine Albiston, “Institutional Inequality,” Wisconsin Law Review 2009 (2009): 1106. ↑