PTI Photo by S Irfan

The Policy and its Aims

At midnight on November 8, 2016, Mr. Narendra Modi, the Prime Minister (PM) of India, declared in a broadcast to the nation that the two highest currency notes—Rs. 500 and Rs. 1000—would immediately cease to be legal tender. This move was considered a very drastic and bold step, especially since nearly 86% of all the currency by value in India was in the form of either Rs. 500 or Rs. 1000 notes.

During his speech, the PM cited three primary reasons for this move. First was the growing stash of black money in the country (Black money in India generally refers to funds earned on the black market, on which income and other taxes have not been paid or which is the proceeds of criminal activity such as bribery, kickbacks and corruption), which, if kept as cash, would mostly be stored in these highest currency denominations. The second motive was to tackle the high number of counterfeit notes in the economy, which again were most prevalent in these two denominations. As per the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), 63% of all the fake currency in India was in the form of Rs. 500 and Rs. 1000 notes in 2015-16 (Reserve Bank of India, Annual Report-2015-16). The third reason cited for this move was to rein in terrorism. It is generally believed that a significant portion of counterfeit currency is supplied by terrorist organizations and is also mostly used to fund terrorism within the country – a fact to which the Prime Minister alluded to in his speech[1] on the 8th of November, 2016.

The decision to demonetize these notes was kept fully confidential: only the PM, the Finance Minister, and the Reserve Bank’s Governor had knowledge of it, six months prior to the announcement (to make the necessary arrangements). For the move to be effective in tackling black money—so that people could not make prior arrangements for securing their black money in the form of other cash—this entire demonetization project had to be handled secretively.

The Policy in Action

The demonetization policy was immediately put into effect from the moment of the PM’s address to the nation. In place of the old currency notes, the RBI introduced and circulated a new denomination of Rs. 2000 notes. While the earlier form of Rs. 500 notes were banned and Rs. 1000 note ceased to exist altogether, a new series of Rs. 500 notes was introduced and circulated by December 22, 2016.

The rules of the policy initially stated that, starting November 10, people could go to the banks to exchange their old currency notes for the new ones. Even people without bank accounts (mostly the poor in both, urban and rural areas) could exchange their old currency notes by showing a proper identification document. Old currency notes still would be acceptable for certain payments—towards fees, charges, hospital bills, petrol pumps, taxes and penalties payable to the central and state. Cash withdrawals from bank accounts, conducted over bank counters, were restricted to a limited amount of Rs. 10,000 per day, and subject to an overall limit of Rs. 20,000 a week. Cash withdrawals from ATMs were restricted to Rs. 2,000 per day per card up to November 18, 2016, and the limits raised to Rs. 4000 per day per card from November 19, 2016. The banks (and ATMs) were to remain shut on November 8 (and 9), the two days immediately following the PM’s announcement, to prepare for this process and to recalibrate machines. The facility for exchanging the withdrawn denominations of Rs. 500 and Rs. 1000 would be available till December 30, 2016. The citizens of the country were encouraged by the PM, to go cashless and switch over to more transparent modes of payment, such as pre-paid cards, credit and debit cards, mobile banking, and internet banking, to ease the process and to aid in turning India into a cashless economy[2]. Old currency notes still would be acceptable for certain payments—towards fees, charges, hospital bills, petrol pumps, taxes and penalties payable to the central and state governments (including municipal and local bodies), payment of utility charges for water and electricity, etc. till November 24.

Over the days following the PM’s announcement, the guidelines for withdrawal limits from the banks, exchange limits, etc. changed more than 15 times in response to the “ground realities”—which caused much confusion in the public at large.

Evidence for the policy

Since November 8, the government’s primary emphasis was the role of demonetization in fighting black money. Black money is a huge problem in India—as per a report by McKinsey and Company, in 2013 the shadow economy made up more than a quarter of the country’s GDP (Basu 2016). But in the past five years, income tax department raids have found that only 5-6% of black money in India is kept in the form of hard cash (Keohane 2016). Most of the black money is either laundered into the system or is used to buy other assets like gold, jewelry, real estate, or foreign investments, or it is stashed in international currency abroad. As per the report, hardly anyone keeps stashes of cash at home anymore (Venugopal et al. 2016). Another point raised by Nobel laureate and economist Paul Krugman was that indeed, to curb black money, getting rid of high-value notes makes sense—since it gets difficult to store black money in small denominations for high amounts of money. In describing the Indian government’s policy action, Krugman adds, “But that did not happen here. High-value notes are not being eliminated”. Instead the government has planned to introduce an even higher denomination (the Rs. 2000) note which make it even easier to hoard illegal cash (Economic Times, December 2, 2016).

Another reason cited for the policy initiative was to deal with counterfeit of these high denomination currency notes in India. As per a study done by Indian Statistical Institute, Rs. 400 crore (i.e. Rs. 4 billion, approx. USD 62.23 million) worth of fake currency is in circulation in the country at any given time (“Fake Notes Worth Rs 400 Crores in Circulation – Times of India” 2016). This is an incidence of fake currency of 0.022% – a meagre impact of a policy that caused large scale inconveniences and social costs.

The third point the PM marshaled in support of demonetization was that it would help counter the terrorist activities being funded by these currency notes. In the short run, he added that surely the terrorist activities will be stalled by terrorists not having access to the new currency. But what is unclear is how demonetization will be a permanent solution. There seems to be no deterrence created to stop terrorists from being funded by new fake currency of the new higher-denomination notes as, one report indicates that the new Rs. 2000 notes were found with two terrorists killed in an encounter in Kashmir on November 22 (“Terrorists Killed In Kashmir’s Bandipora Had New Rs 2,000 Notes, Say Police” 2016).

Implementation Arrangements

Even people from within the Indian government and strong supporters of PM Modi have not shied away from voicing their opinion against the weak and ill-thought-out implementation of this demonetization policy.

A 2012 estimate, carried out by The Fletcher School at the Tufts University, estimated that 86.6% of the transactions in India were in cash (Rowlatt 2016). Needless to say, almost everyone in the country had to run to the banks to get the new currency notes, either immediately, to carry out their daily activities, or after a few days, since the cash they had would be merely paper if it were not exchanged by December 30. This sudden demonetization resulted in a huge demand for the new currency notes and for old smaller demonization notes which were still legal tender; the RBI’s failure to print and supply notes to meet these demands resulted in extremely long queues outside banks and ATMs (for those who did use plastic money). Many reports from all over the country surfaced that people had to go to the bank for consecutive days and stand in lines for the full length of the day(s), starting as early as 5 AM, to get their cash converted, since the banks and ATMs ran out of cash quite quickly. As of November, 18, just 10 days after the policy announcement, there had been a total of 55 reported deaths attributed to exhaustion after standing for long hours in queues (“Day 9: Demonetisation Death Toll Rises To 55” 2016). Despite the exceptions stated in the order, reports from across the country noted that some private hospitals refused to accept old notes from patients and their families, which resulted in additional avoidable deaths.

To add to the problem of insufficient cash reaching the banks and ATMs, only 28%-32% of Indians even had access to financial institutions (banks and post offices). Further, 33% of the 138,626 bank branches are in 60 Tier-1 and Tier-2 cities, leaving rural India at a huge disadvantage (“Why Govt’s Demonetisation Move May Fail to Win the War against Black Money” 2016). Only 27% of Indian villages have a bank within 5km (Rowlatt 2016), which further adds to the costs their residents face in having to travel to faraway bank branches.

Lack of new currency reaching the banks was a major a problem faced by citizens of the capital city and other Tier 1 cities in India. The situation of supplying the new currency notes in rural India was much worse, and it is in the rural areas where most of the transactions take place in cash.

Apart from the lack of supply of the new currency notes and of old smaller denomination notes to replace the outdated Rs. 500 and Rs. 1000 notes, another problem was that ATM machines were not able to dispense the Rs. 2000 notes due to the bill’s different size. As a result, the only notes available in ATMs were old Rs. 100 notes, which, due to the smaller denomination, would stock the ATM with a lesser value of currency overall; this resulted in even longer lines and waiting time, since the ATMs got depleted fast. These machines needed to be re- calibrated after November 8 to be able to dispense the new notes. As of December 1, about 90% of the machines, around 180,000 ATMs, had been re-calibrated.

Since December 1 marked the beginning of a new month, many pension seekers also faced troubles in accessing their pensions from the banks. Due to withdrawal limits and long queues, elderly and physically incapable pensioners found it exhausting to stand in these lines and visit thee. Many complained and suggested that there should have been separate rules and lines for pensioners.

The Effects of Demonetization on Special Sections of the Society

Businesses

Big business and corporate houses, mostly in the service sector and in cities, did not face any significant effects due to demonetization, since most of their activities and payments takes place through the formal financial economy and uses net banking. But the story was very different for small and medium enterprises and their workers. Take Tirupur, a town in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu that produces annually some Rs. 32,000 crore (Rs. 320 billion = approx. USD 4.97 billion) worth of knitwear, three-fourths of which is exported. Factories in this ‘knitwear capital of India’ employ an estimated five hundred thousand l women and men, involved in fabric cutting, stitching, ironing, and packing of garments, as well as other related activities. Out of these five hundred thousand, half or more are paid weekly wages in cash. A unit may have 1,000 employees, of whom 500 receive an average of Rs. 2,000 a week. It translates into weekly cash disbursements of Rs. 10 lakh (Rs. 1 million = approx. USD 15,559) as wages, whereas business entities were being allowed to withdraw just Rs. 50,000 in cash per week from their current accounts maintained with banks. While the cash withdrawal limit was even lower, at Rs. 20,000, at the beginning of the demonetization regime, the later increase to a withdrawal limit of Rs. 50,000 per week was still nowhere near what is required to pay full wages to all workers (“In Fact: When the Money Stops” 2016).

Similar stories resulted in far worse consequences in other parts of the country, where, due to lack of cash, factory owners were unable to make payments to their daily/weekly workers. A jute mill in Howrah district of West Bengal has temporarily shut down making 2500 people unemployed. Due to lack of jobs many daily wage earners began to leave cities,going back to their respective villages. In Gurgaon, for example, 1000 workers have left due to lack of work opportunity. One study suggests that a total of 400,000 jobs could be lost due to demonetization.

Another sector hit hard by this move has been the agriculture sector in India. This is worrisome since most of the rural part of the country—and 55% of Indians overall—are employed in the agricultural sector. 60-70% of the produce went to waste because the agriculture supply chain was disrupted by cashlessness (“70% Vegetables Going Waste, Prices Nose-Dive – Times of India” 2016). Most of the agriculture supply chain in the country is based on cash, and with a cash crunch, the prices of vegetables and fruits have plummeted. Reports suggest that the seasonal nature of agriculture and allied businesses means that the losses incurred over would have ripple effects on farmers’ incomes throughout the next year2017.

Small road-side vendors, who again work just with cash, are also faced difficulties due to the cash crunch. Reports from all over the country state that vendors selling food on carts, selling fruits and vegetables, fishes, small trinkets, etc. have lost almost 70-80% of their business due to cashlessness.

Poor

The government is encouraging people to go cashless and use other forms of payments like plastic money and net banking. The problem faced by the poor here is that approximately 165 million Indians do not have banks accounts (Venkataramakrishnan 2016) and most of them are financially illiterate. Only 40% of adults in India can fill out a form, and almost all of these people (without bank accounts, financially illiterate, and possessing very basic literacy in general) fall into the poor category. Hence, their only option is to work with cash, and the shortage of cash has severe problems for this portion of the Indian population.

As mentioned above, the agricultural supply chain has been hit hard. At the start of the chain are farmers. Most of the farmers in India are small farmers with less than 5 acres of land; these farmers have faced the brunt of the policy’s effects. Since they operate solely on cash, the resulting cashlessness has left them unable to sell their produce or buy raw materials. Not having enough savings to back them up made this drop in supply detrimental for them.

The situation is similar for low-skilled daily/weekly earners who work either in manufacturing factories or as construction laborers in semi-rural and urban areas. Due to cashlessness they were deprived of their daily jobs. Since, again, this disadvantaged section of society often does not have savings, these workers rely on their daily wages to feed themselves and their families. A recent report stated that many are living off one meal a day or are doing without any food for a day or two each week (Kakodkar et al. 2016).

As per the estimates and projections of Aadhaar card (a unique identification card card linked in many cases to direct subsidy transfers, issued by the Unique Identification Authority of India) holders, almost 58 million Indians do not have any form of identity document (Gopalakrishnan 2016). Practically every household in India keeps cash at home for transactions and emergencies (one of the few studies in this regard showed that those in the lowest income quintile kept 59% of their savings as cash at home). These people cannot even get their old currency notes exchanged at the banks in many cases.

Another problem faced by these workers is the time spent in standing in lines. Since these workers rely on their daily earnings to even get two meals each day, standing in lines to exchange their old currency notes costs them more than just time (Bhan 2016). This additional expense results in people borrowing money, which exposes these people—who are on the brink of poverty line—to debt and, in worse cases, can lead up to welfare shocks (a change in consumption per capita bringing the household below a socially defined minimum level).

Economy

Demonetization has been said to be damaging the Indian economy severely. According to The Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy (CMIE), the nation’s GDP is likely to take a hit of Rs 1.28 lakh crore (i.e. Rs. 1.28 trillion, approx. USD 19.9 billion) for the period between November 8 and December 30, 2016. That estimate does not, however, consider the cost for the next quarter—and most economists believe it will take at least one, if not more, quarters before the economy recovers. They expect the total cost to the GDP, at the minimum, to be around Rs 1.5 lakh crore (i.e. Rs. 1.5 trillion, approx. USD 23 billion). Dr. Manmohan Singh, a former Prime Minister, Finance Minister, RBI governor, and economist, has suggested that this move could reduce the country’s gross domestic product by 2% or more (“Demonetisation is organised loot, could lower GDP by 2%, says Manmohan Singh” 2016). According to a Deutsche Bank report, India’s real GDP growth is expected to slow to 6.5 % in the current fiscal year (“India’s Growth Likely to Slow to 6.5% due to Demonetisation: Deutsche Bank Report” 2016).

The Nikkei India Services Business Activity Index sharply fell to 46.7 in November from 54.5 in October. The seasonally adjusted Nikkei India Composite Purchasers Managers Index (PMI) Output Index dipped from October’s 55.4 to 49.1 in November (Suneja et al. 2016).

“Considering the fact that the informal sector in India accounts for about 45% of GDP and nearly 80% of employment, disruption of this liquidity can be very costly indeed, both in terms of growth and equity,” said Pronab Sen, country director of the India Central Programme, International Growth Centre (Sen 2016). Dr. Sen here is talking about all the daily wage earners and vendors (which constitute much of India’s poor population). He adds, “There is, however, one component of the economy that may actually experience a permanent effect—the informal financial sector. This sector, comprising not only the much-reviled moneylender but numerous other institutions such as nidhis, hundis, chit funds, etc., will have a very hard time exchanging its stock of currency (some of which may well be black money), and may indeed suffer a permanent erosion in its lending capacity” (Sen 2016). This informal financial sector is roughly the same size as 40% of India’s formal financial sector.

Assessing the Demonetization Policy from a Policy Maker’s Point of View

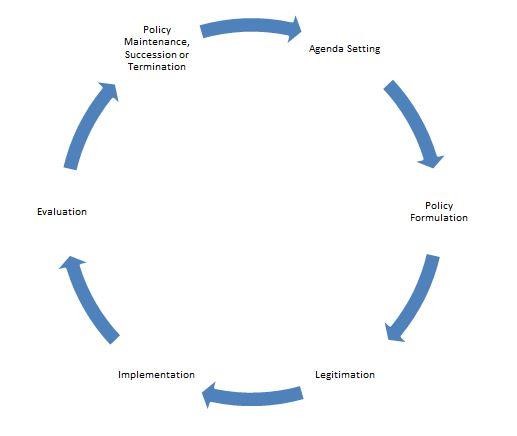

One of the best practices in studying policymaking is to break policy production down into stages. A policy cycle divides the policy process into a series of stages.

- Agenda Setting: This is the preliminary stage, when one identifies the problems that require government attention, decides which issues deserve the most attention, and defines the nature of the problem.

- Policy Formulation: At this stage the goals, outputs, and outcomes are set, and the costs and effects of various solutions are assessed. Subsequently, the process of choosing from a list of solutions and selecting a policy such that the benefits outweigh the costs takes place.

- Legitimation: In this step of the cycle, one ensures that the chosen policy instruments have support. Support can originate from one or a combination of: legislative approval, executive approval, consent sought through consultation with interest groups, and referenda.

- Implementation: Next, the government establishes or employs an organization or a group of people from within the government to take responsibility for implementation, ensures that the organization has the resources (such as staffing, money and legal authority) to do so, and makes sure that policy decisions are carried out as planned.

- Evaluation: The government then assesses the extent to which the policy was successful or the policy decision was the correct one—the criteria governing this assessment focus on whether the policy was implemented correctly and, if so, whether it had the desired effect.

- Policy maintenance, succession or termination: Finally, the government considers if the policy should be continued, modified, or discontinued (Cairney 2013).

Since the demonetization policy is still in its implementation stage, we cannot assess its last two stages. But we can surely shed some light on the first four stages.

As mentioned before, a main motivation for implementing the policy was reduction of black money within the Indian economy. The policy did have two other motives too—curbing counterfeit currency and stalling terrorist activities, but the primary target of the policy was black money.

In the policy formulation stage of India’s demonetization policy, one can find many areas where best practices were not followed. Considering that the aim of the policy was to curb black money, it is not clear why the government took such a drastic measure, since data show that only 6% of black money is stored in the form of cash, and since the costs of this policy have proven so high. In terms of monitory costs, the expenditure involved in printing new currency, recalibrating ATMs, and exchanging the old currency amounts to Rs. 1.28 lakh crore (Rs. 1.28 trillion). Additional public money has been spent to advertise the policy. And then there are the other costs discussed above—huge costs faced by the Indian economy and inconvenience costs shouldered by citizens, especially the poor.

Since the policy had to be effected abruptly and its implementation had to involve a minimal number of people, the government could not legitimize demonetization through the conventional routes of asking experts, seeking legislative or executive approval, seeking approval from the concerned parties, etc. Even though these options were closed for the government, the government could have checked whether demonetization had previously been done elsewhere in the world and could have studied how it fared in those contexts. None of the countries which had previously implemented demonetization were able to successfully achieve their stated goals for the policy. Almost all the countries which implemented demonetization—the USSR, Zaire, Ghana, Myanmar, Nigeria and North Korea—did so to curb corruption and were either under a dictator or military rule. Almost all the countries faced many problems and the policy led to major loss in faith in the government. In many cases, demonetization led either to coups or to the overthrowing of the dictator who implemented it. Even independent India had tried demonetization before, in 1977, but at that time the policy had minimal consequences: very few had such big currency notes, and because people were aware of the policy beforehand and made prior arrangements, even black money was tough to catch. In fact, even the previous government led by the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) from 2009 to 2014 had suggested demonetization (though not on this scale); the then-governor of the RBI rejected the proposal and it never went through.

Lastly, as discussed above, there were various issues with the implementation of the policy, stemming from a lack of proper planning and preparation for the demand for new notes. The notes were not printed and kept ready in advance, and they were not distributed beforehand or immediately after. The ATM machines were not calibrated to accommodate the new size of the new currency. No special infrastructure was created to cater to the rural population, for whom banks are few and far between.

Demonetization Backfiring

Apart from the fact that the gains of the demonetization policy seem far outweighed by its costs and its disastrous implementation, which is proving especially harsh on poor and honest citizens who were not the target of the policy, many other factors have made people question the motives of the government.

First and foremost, going by the RBI data, there had been a substantial surge in bank deposits in 2016’s July-September quarter. Total deposits garnered by the Indian banks rose by an abnormal Rs. 6,64,800 crore (approx. USD 103 billion) in that quarter, to a record Rs. 102.08 lakh crore (i.e. Rs. 102.08 trillion, approx. USD 1.59 trillion). This is the highest quarterly jump ever recorded. It has been alleged that this jump could have been a result of the news leaking – which gave an undue advantage to those in the knowhow of the policy to make bank deposits and convert their black money. News reports suggest that jewelers in many parts of the country worked overtime through the night of November 8 and 9 to help convert 500 and 1,000 rupee notes into gold (Rowlatt 2016), again substantiating the allegation that the news of demonetization was leaked to certain people of the PM’s political party—Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP)—beforehand.

Other reports of corruption and favoritism on the part of BJP for its own party members and friends have also surfaced. In Tamil Nadu, a BJP member was arrested with 900 new Rs. 2000 notes as the party member was unable to “give satisfactory explanation for the source of the money”.

Secondly, PM Modi all throughout his election campaign had talked about being extremely strict on black money holders, however, in reality the policy action has been insufficient. According to RBI data, of the Rs. 15.4 lakh crore (i.e. Rs. 15.4 trillion) of scrapped money (due to the demonetization policy), it was estimated that 30%—around Rs. 4.5 lakh crore (Rs. 4.5 trillion)—was black. The most conservative estimate assumes that about a third of the unaccounted money—or Rs. 1.5 lakh (Rs. 1.5 trillion) crore—was fraudulently adjusted as “legitimate” money, either through backdated purchases or other ways of laundering black money.

As per the new income disclosure scheme that the government announced on November 28, people can deposit unaccounted-for money (black money) with a 50% tax on the amount declared. Because of this law, even black-money hoarders will be able to deposit their money while only paying a 50% “fine”. The income tax department will then have to sort through all these deposits to figure out these depositors to catch the hoarders. But recovering tax from deposits would be a tricky task. In the first place, tax disputes can go on for years and secondly, there are just around 6,000 sanctioned positions of Income Tax IT officers in India, around 1,000 of which are vacant and hence, the income tax department does not have the adequate personnel to identify those accounts that need to be taxed.

The combination of all these factors makes citizens question whether this move was well-intentioned, with proper thought and planning, or was instead just the government trying to gain popularity before the upcoming Uttar Pradesh state elections (which actually gave BJP a popular advantage in the Uttar Pradesh elections, where BJP won).

Lessons Learnt

The positive policy takeaways from India’s demonetization experiment are the role of civil society and media. Since the announcement, both citizens and media have played an active role in voicing their opinion and criticizing the policy whenever it increased the hardships faced by the people. They have held the government accountable, which is essential for any policy-making and -implementing organization. This accountability has consequently led the government to take remedial actions and change the rules of the policy in order to ease the problems faced by the citizens on the ground.

As mentioned above, there have been various issues with not only the policy’s implementation but even with other, earlier aspects in the policy cycle. Even though the agenda for the policy (reducing black money) was well defined, the government may have made an error in deciding whether demonetization was the best way to deal with the black money problem. The government did not tackle the problem from its root and seems to have not its homework properly, considering the absence of any mitigation plans or the governmental action to deal with the unexpected fallout of the policy. Had the government conceded to the data, it might have realized that demonetization would only be able to eliminate, at maximum, 6% of India’s black money, because only that much was in the form of cash in the first place. Had the government taken into account other countries’ experiences with demonetization it would have seen that the move has never been successful.

The problem, then, was twofold: choosing the wrong policy instrument (demonetization) in dealing with the problem at hand (black money), and implementing it improperly.

Kenneth Rogoff, the former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund, has written that, “In general, a slow gradual currency swap would be far less disruptive in an advanced economy, and would leave room for dealing with unanticipated and unintended consequences.” He adds, “Instead of eliminating the large notes, India is exchanging them for new ones, and also introducing a larger, 2000-rupee note, which are also being given in exchange for the old notes” and suggested that large noted should have been eliminated entirely.

The country did not have proper infrastructure in place to demonetize 86% of the currency by value. Rural parts of the country did not have the required capability to meet demand for the new currency, and there was not enough supply of the new currency—all of which led to various problems being faced by the citizens. Beyond the basic issues of supply and demand for the new currency, India’s rural population was disproportionately affected by these changes because most people living in rural areas are illiterate and have no financial literacy, let alone bank accounts. The government should have taken these points into consideration and should have tackled these issues before expecting people to go cashless.

All these issues point towards the importance of breaking a policy process into different stages of a policy cycle and focusing on each of these different stages by doing proper research in designing and implementing an effective and successful policy.

References

- “Reserve Bank of India- Annual Report- 2015-16,” n.d., https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/AnnualReport/PDFs/0RBIAR2016CD93589EC2C446779 3892C79FD05555D.PDF.

- Kaushik Basu, “In India, Black Money Makes for Bad Policy,” The New York Times, November 27, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/27/opinion/in-india-black-money- makes-for-bad-policy.html.

- David Keohane, “The Curse of Indian Cash Scrapping | FT Alphaville,” accessed December 10, 2016, https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2016/11/21/2180031/the-curse-of-indian- cash-scrapping/.

- Vasudha Venugopal et al., “Demonetisation in a Booming Economy Is like Shooting at the Tyres of a Racing Car: Jean Drèze,” The Economic Times, accessed December 9, 2016, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/opinion/interviews/demonetisation-in-a- booming-economy-is-like-shooting-at-the-tyres-of-a-racing-car-jean- drze/articleshow/55547554.cms.

- IANS | Updated: Dec 02, 2016, “Demonetisation Unusual, Gains Not Clear: Nobel Winner Paul Krugman,” The Economic Times, accessed December 9, 2016, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/demonetisation-unusual- gains-not-clear-nobel-winner-paul-krugman/articleshow/55751129.cms.

- “Fake Notes Worth Rs 400 Crores in Circulation – Times of India,” The Times of India, accessed December 10, 2016, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Fake-notes-worth- Rs-400-crores-in-circulation/articleshow/52214965.cms.

- “Terrorists Killed In Kashmir’s Bandipora Had New Rs 2,000 Notes, Say Police,” NDTV.com, accessed December 10, 2016, http://www.ndtv.com/india-news/terrorists- killed-in-kashmirs-bandipora-had-new-rs-2-000-notes-say-police-1628589.

- PTI | Updated: Dec 01, 2016, and 06 11 Pm Ist, “1.80 Lakh ATMs Re-Calibrated to Dispense Rs 500, 2,000 Notes,” The Economic Times, accessed December 10, 2016, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/banking/finance/banking/1-80-lakh-atms- re-calibrated-to-dispense-rs-500-2000-notes/articleshow/55727656.cms.

- Justin Rowlatt, “Can India’s Currency Ban Really Curb the Black Economy?,” BBC News, November 10, 2016, sec. India, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india- 37933231.

- “Day 9: Demonetisation Death Toll Rises To 55,” Huffington Post India, accessed December 10, 2016, http://www.huffingtonpost.in/2016/11/17/day-9-demonetisation- death-toll-rises-to-55/.

- “Why Govt’s Demonetisation Move May Fail to Win the War against Black Money,” Http://Www.hindustantimes.com/, November 12, 2016, http://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/cash-has-only-6-share-in-black-money- seizures-reveals-income-tax-data/story-JfFuTiJYtxKwJQhz2ApxlL.html.

- “Pensioners Too Face the Demons of Demonetization – Times of India,” The Times of India, accessed December 10, 2016, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nagpur/Pensioners-too-face-the-demons-of- demonetization/articleshow/55714251.cms.

- “In Fact: When the Money Stops,” The Indian Express, November 15, 2016, http://indianexpress.com/article/explained/demonetisation-utility-bills-household-bill- 4375665/.

- “Demonetisation Effect: 2,500 Lose Jobs as Howrah Jute Mill Shuts,” Http://Www.hindustantimes.com/, December 6, 2016, http://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/demonetisation-effect-2-500-lose-jobs-as- howrah-jute-mill-shuts/story-VYZZHTrJZ5zmzjL0YfHUIK.html.

- “Demonetisation Blues: No Work or Cash, over 10,000 Daily Wagers Leave Gurgaon,” Http://Www.hindustantimes.com/, December 7, 2016, http://www.hindustantimes.com/gurgaon/daily-wage-workers-start-leaving- gurgaon/story-Xo3IFCwrSaUXGHmvJO6JTL.html.

- “Demonetisation Could Take Away 400,000 Jobs;e-Com to Be Worst Hit,” Http://Www.hindustantimes.com/, December 8, 2016, http://www.hindustantimes.com/business-news/demonetisation-could-take-away-400- 000-jobs-e-com-to-be-worst-hit/story-Fum0FvfDkp7ClUyYfTjvrM.html.

- “70% Vegetables Going Waste, Prices Nose-Dive – Times of India,” The Times of India, accessed December 9, 2016, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/lucknow/70- vegetables-going-waste-prices-nose-dive/articleshow/55863243.cms.

- “Tomato At 50 Paise/Kg! A Windfall or Disaster?,” Countercurrents, December 8, 2016, http://www.countercurrents.org/2016/12/08/tomato-at-50-paisekg-a-windfall-or-disaster/.

- Ajoy Ashirwad Mahaprashasta, “In Bundelkhand, Farmers Sink Into Debt As Rural Economy Collapses,” The Wire, December 8, 2016, http://thewire.in/85322/in- bundelkhand-farmers-sink-into-debt-as-rural-economy-collapses/.

- “Women Vendors Who Exist on Cash Income Hit Hardest by Demonetisation,” Http://Www.hindustantimes.com/, November 18, 2016, http://www.hindustantimes.com/columns/women-vendors-who-exist-on-cash-income-hit- hardest-by-demonetisation/story-7haNzOCwqHN2eHH7ZBumcM.html.

- “Demonetisation Tsunami Hits Women In Kerala Fishing Village,” Huffington Post India, accessed December 9, 2016, http://www.huffingtonpost.in/village- square/demonetisation-tsunami-hits-women-in-kerala-fishing-village/.

- Priyanka Kakodkar et al., “Jobless, These Labourers Can Barely Get One Meal a Day,” The Economic Times, accessed December 11, 2016, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/jobless-these-labourers- can-barely-get-one-meal-a-day/articleshow/55920755.cms.

- Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, “Demonetisation: India’s Unbanked Population Would Be the World’s 7th-Largest Country,” Text, Scroll.in, accessed December 11, 2016, http://scroll.in/article/822464/demonetisation-indias-unbanked-population-would-be-the- worlds-7th-largest-country.

- Gautam Bhan, “Demonetisation Isn’t an Inconvenience for Poor People – It Risks Causing a Welfare Shock,” Text, Scroll.in, accessed December 9, 2016, http://scroll.in/article/821599/demonetisation-will-do-what-illness-accident-eviction- funeral-or-drought-do-to-poor-families.

- Shankar Gopalakrishnan, “Demonetisation Is a Permanent Transfer of Wealth from the Poor to the Rich,” Text, Scroll.in, accessed December 9, 2016, http://scroll.in/article/822402/demonetisation-is-a-permanent-transfer-of-wealth-from- the-poor-to-the-rich.

- IANS | Dec 07, 2016, and 09 53 Pm Ist, “All Pain, Little Gain: Demonetisation Math Does Not Add up,” The Economic Times, accessed December 9, 2016, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/all-pain-little-gain- demonetisation-math-does-not-add-up/articleshow/55854776.cms.

- Scroll Staff, “Demonetisation Is Organised Loot, Could Lower GDP by 2%, Says Manmohan Singh,” Text, Scroll.in, accessed December 9, 2016, http://scroll.in/latest/822380/demonetisation-is-organised-loot-could-lower-gdp-by-2- says-manmohan-singh.

- “India’s Growth Likely to Slow to 6.5% due to Demonetisation: Deutsche Bank Report,” The Indian Express, November 25, 2016, http://indianexpress.com/article/business/banking-and-finance/indias-growth-likely-to- slow-to-6-5-due-to-demonetisation-deutsche-bank-report-4394635/.

- Kirtika Suneja et al., “Demonetisation Hits Services, PMI Shrinks after 16 Months,” The Economic Times, accessed December 9, 2016, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/indicators/demonetisation-hits- services-pmi-shrinks-after-16-months/articleshow/55805436.cms.

- PTI | Updated: Nov 28, 2016, and 03 00 Pm Ist, “Foreign Investors Pull out close to $5 Billion so Far in November on Demonetisation Drive,” The Economic Times, accessed December 9, 2016, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/stocks/news/foreign- investors-pull-out-close-to-5-billion-so-far-in-november-on-demonetisation- drive/articleshow/55648776.cms.

- Pronab Sen, “Demonetization Is a Hollow Move,” Http://Www.livemint.com/, November 14, 2016, http://www.livemint.com/Opinion/uzvIE84KGXy1xvp06pTazM/Demonetization-is-a- hollow-move.html.

- Paul Cairney, “Policy Concepts in 1000 Words: The Policy Cycle and Its Stages,” Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy, November 11, 2013, https://paulcairney.wordpress.com/2013/11/11/policy-concepts-in-1000-words-the- policy-cycle-and-its-stages/.

- “Demonetisation Explained in Numbers: Why India’s Cash Crunch Is Such a Big Deal,” accessed December 10, 2016, http://www.dailyo.in/business/demonetisation-currency- change-narendra-modi-bjp-infographics-atm-bank-rural-urban-paytm/story/1/14236.html.

- Bloomberg | Nov 16, 2016, and 09 14 Pm Ist, “PM Modi, Please Take Note: These Countries Tried Demonetisation and Failed,” The Economic Times, accessed December 9, 2016, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/forex/pm-modi-please-take-note- these-countries-tried-demonetisation-and-failed/articleshow/55453335.cms.

- “History of Demonetisation: When Morarji Desai Government Ceased Rs 500, Rs 1000 and Rs 10,000 Notes,” The Financial Express, November 9, 2016, http://www.financialexpress.com/economy/history-of-demonetisation-when-morarji- desai-government-ceased-rs-500-rs-1000-and-rs-10000-notes/441874/.

- “RBI Had Declined Demonetisation Proposal during UPA-II Regime, No Rationale behind Ongoing Drive: Former RBI Deputy Governor,” accessed December 10, 2016, http://en.southlive.in/india/2016/11/18/rbi-had-declined-a-proposal-for-demonetisation- during-upa-ii-regime-no-rationale-behind-ongoing-drive-former-rbi-deputy-governor.

- “Rs 500, Rs 1,000 Note Ban: Why Arvind Kejriwal’s Charges against BJP Need to Be Probed,” Firstpost, accessed December 11, 2016, http://www.firstpost.com/politics/rs- 500-rs-1000-note-ban-why-arvind-kejriwals-charges-against-bjp-need-to-be-probed- 3102118.html.

- “Over 900 New Rs 2000 Notes Seized from TN BJP Leader Who Backed Demonetisation,” Http://Www.hindustantimes.com/, December 2, 2016, http://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/over-900-bills-of-rs-2000-seized-from-tn- bjp-leader-who-backed-demonetisation/story-akRx5YDntU3erDWVE2IxxN.html.

- “Modi Govt Says Demonetisation Strikes Black Money; RBI Data Says It’s a Damp Squib – Firstpost,” accessed December 11, 2016, http://www.firstpost.com/business/economy/demonetisation-modi-govt-clains-giant- killing-of-black-money-but-rbi-data-shows-a-damp-squib-3130208.html.

- “Demonetisation: How Narendra Modi Changed Narrative from Black Money to Cashless Economy – Firstpost,” accessed December 11, 2016, http://www.firstpost.com/politics/note-ban-how-narendra-modi-changed-narrative-from- black-money-to-cashless-economy-3127628.html.

- “10 Reasons Why BJP’s Demonetization Move Is An Unmitigated — And Politically Motivated — Disaster,” Huffington Post India, accessed December 11, 2016, http://www.huffingtonpost.in/apoorva-pathak/10-reasons-why-bjps-demonetization- move-is-an-unmitigated-and/.

- “Demonetisation Should Be Gradual And Eliminate Large Notes Entirely, Says Harvard Economics Professor,” Huffington Post India, accessed December 9, 2016, http://www.huffingtonpost.in/2016/11/20/demonetisation-should-be-gradual-and- eliminate-large-notes-entir/.