Author: Parmis Mokhtari-Dizaii

Edited by: Alejandro Ramos

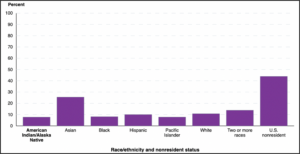

The United States has long been a global leader in higher education, attracting millions of international students with promises of academic freedom, cutting-edge research, and career opportunities. However, the State Department’s newly launched “Catch and Revoke” initiative threatens this reputation.1 This AI-driven surveillance program monitors the social media activity of foreign student visa holders, aiming to identify and revoke visas of individuals deemed supportive of designated terrorist organizations. While framed as a national security measure, the policy raises serious concerns about due process, free speech, and its broader implications for international students and U.S. higher education. This is particularly significant given that, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, nearly half of graduate students in STEM fields at U.S. degree-granting institutions are nonresidents (Figure 1).2 Critics warn that such measures could deter top global talent, worsening the already declining trend in international student enrollment and accelerating the brain drain of skilled workers to other nations. In the end, a policy intended to protect national security may instead cost the United States its global academic edge.

Figure 1. Master’s Degrees in STEM by Race/Ethnicity and Residency Status (2021–22)

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), Completions component, Fall 2022 (provisional data).

AI Surveillance and the Erosion of Due Process

The “Catch and Revoke” initiative signifies a major escalation in the application of artificial intelligence (AI) within immigration enforcement.3 This program utilizes machine-learning algorithms to scrutinize various data sources, including social media activity, participation in protests, and historical records like past arrests or disciplinary actions. While AI systems are highly effective at processing large datasets, they inherently lack the capacity to accurately interpret the subtleties inherent in political discourse, satire, or culturally specific references.4 This limitation raises substantial concerns among advocates of free speech, who caution that such automated systems are prone to misinterpretations.5 Consequently, individuals may face deportation based on classifications that are arbitrary or erroneous. Empirical evidence highlights these concerns; for instance, a 2019 study revealed that automated content moderation tools were up to two times more likely to flag content posted by Black users and misidentify hate speech in texts written in African American English.6 These findings point to the potential for AI-driven systems to perpetuate existing biases, thereby jeopardizing the principles of due process and freedom of expression.

Moreover, the opacity of AI decision-making processes exacerbates these issues. Often characterized as “black box” systems, AI algorithms operate without transparent mechanisms for external scrutiny or accountability.7 This lack of explainability limits affected individuals’ ability to understand or contest decisions that have profound implications on their lives, such as visa revocations. Looking beyond the United States, the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) tackles similar concerns by giving individuals the right not to be subject to decisions made solely through automated processing, highlighting the need for human oversight in crucial decisions.8 In the context of the “Catch and Revoke” initiative, the absence of such safeguards may lead to unjust outcomes, particularly for international students who are actively engaged in political or academic discussions.

The Case of Mahmoud Khalil: A Warning Sign

The recent case of Mahmoud Khalil’s detention highlights the real-world implications of AI-driven surveillance policies like “Catch and Revoke,” which risk targeting individuals based on political beliefs rather than legal violations. Khalil, known for organizing and leading pro-Palestinian demonstrations, was arrested by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents at his university-owned apartment in Manhattan on March 8, 2025.9 Initially, agents cited the revocation of his student visa; upon discovering his status as a legal permanent resident, they shifted to revoking his green card.10 This abrupt action, lacking clear charges, has raised significant concerns among legal experts about the potential misuse of AI surveillance to unjustly target individuals based on their political activities rather than any concrete legal infractions.11 Trump has since stated that Khalil’s arrest is just the beginning of “many to come,” raising concerns that “Catch and Revoke” and similar policies could be wielded to suppress dissent rather than enforce immigration law.12

Khalil’s case ultimately highlights how the Trump administration’s mass deportation efforts intersect with its crackdown on pro-Palestinian student protesters, suggesting that opposition to the administration’s agenda may lead to arrest or deportation.13 The opacity of AI-driven policies like “Catch and Revoke” makes it difficult for individuals to challenge decisions, particularly when these systems have documented biases against marginalized communities. This lack of transparency is particularly alarming in Khalil’s case, where the absence of clear criminal charges in his detention raises serious due process concerns and sets a troubling precedent for using national security as a pretext to suppress political opposition. With reports that the State Department, Department of Justice, and Department of Homeland Security plan to deploy “Catch and Revoke” to monitor foreign students’ political activity, Khalil’s case may be a preview of a broader campaign against those deemed politically inconvenient.14

Implications for International Students and Higher Education

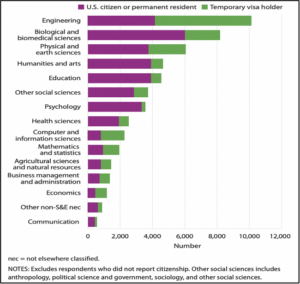

The effects of AI-driven visa revocations extend beyond individual cases, posing risks to the U.S. education system and economy. International students contribute over $40 billion annually to the U.S. economy and serve as a crucial talent pipeline for industries facing labor shortages, particularly in STEM fields.15 Since 2010, temporary visa holders have earned nearly 180,000 of the 585,000 doctorates awarded in the United States, with 56% of all doctorates awarded in science and 31% of those awarded in engineering (Figure 2).16 In 2020, temporary visa holders outnumbered U.S. citizens and permanent residents in earning doctorates in engineering, computer sciences, mathematics, and economics.17 Within engineering, temporary visa holders accounted for about two-thirds of doctorate recipients in electrical, electronics, and communications engineering (68%), industrial and manufacturing engineering (66%), and civil engineering (64%).18 Policies that introduce sweeping, AI-driven scrutiny risk deterring top talent from choosing the United States for higher education, exacerbating the already declining trend in international student enrollment. For instance, the Institute of International Education (IIE) reported an already 15% drop in enrollment between 2019 and 2021, most likely linked to the consequences of the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.19 While numbers have begun to recover, restrictive policies like “Catch and Revoke” could reverse those gains.

Figure 2. Doctorate Recipients by Field and Citizenship Status (2020)

Source: National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Survey of Earned Doctorates, 2020.

Source: National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Survey of Earned Doctorates, 2020.

The Brain Drain Effect and Global Competition for Talent

Beyond the economic consequences, the policy exacerbates a long-term challenge: brain drain. The United States has historically been a magnet for global talent, offering post-graduation work opportunities through programs like Optional Practical Training (OPT) and the H-1B visa.20 However, as visa policies grow more restrictive, highly skilled students and researchers will more likely be looking elsewhere. Canada, for example, has aggressively expanded its immigration pathways, implementing the Tech Talent Strategy, which allows employers to fast-track work permits for highly skilled workers in STEM fields.21 Meanwhile, Germany’s Blue Card has made it easier for international graduates to gain residency and employment.22 If AI-driven visa revocations discourage students from studying in the United States, the long-term effects could be dire for industries that rely on high-skilled immigrants. A 2023 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that while immigrants make up just 16% of U.S.-based inventors, they contribute nearly 25% of all patents and patent citations.23 They are also responsible, directly or indirectly, for 36% of total U.S. patent output.24 Given that immigrants drive a significant share of innovation, policies that reduce the number of international STEM graduates could slow patent production and weaken the country’s technological and economic competitiveness.

While other nations attract global talent, some of the United States’ largest sources of international students are also developing competitive alternatives at home. Countries like China and India, traditionally major sources of outbound students to the United States, are heavily investing in their own higher education infrastructure, as well as in research and innovation, which are key components of technological and economic competitiveness. China’s Double First-Class initiative is aimed at elevating domestic universities to global standards, while India’s National Education Policy 2020 seeks to establish international research collaborations to retain domestic talent.25, 26 If U.S. policies continue to push away international students, other countries will step in to fill the gap, shifting the global balance of innovation and economic competitiveness away from the United States.

Balancing National Security and Civil Liberties

While national security remains paramount, policy approaches must strike a balance between safety and fundamental freedoms. As international students navigate an increasingly precarious landscape, the United States must ensure that technological advancements in enforcement do not come at the cost of fundamental freedoms and due process. Overreliance on AI for visa revocations, without adequate human review or appeals processes, risks unfairly penalizing individuals based on faulty algorithms. To prevent wrongful targeting, strict oversight must be implemented, reinforcing due process protections and ensuring that visa holders have clear pathways to challenge erroneous revocations. Higher education institutions should also take an active role in safeguarding student rights, advocating for fair treatment, and ensuring transparency in visa-related decisions. Additionally, policymakers must consider the broader impact of visa policies on the U.S. economy and global standing in research and innovation. Other nations have recognized the value of foreign talent and are actively adapting policies to attract and retain skilled students. If the United States fails to do the same, it risks losing its competitive edge in the global economy.

Conclusion

The “Catch and Revoke” initiative raises urgent concerns about AI-driven surveillance and its implications for civil liberties. Without appropriate safeguards, such policies risk transforming AI into a tool of suppression rather than security. The United States faces a critical choice: whether to harness AI responsibly or risk allowing it to erode the very freedoms it seeks to protect. Beyond the immediate risks to individual rights, the broader consequences could reshape America’s role as a global leader in education and innovation. Ensuring transparency and oversight in AI-driven enforcement is not just about protecting civil liberties—it is a strategic imperative for maintaining the nation’s commitment to due process, its economic strength in higher education and technology, and its standing on the world stage.

Works Cited

1. Caputo, Marc. 2025. Scoop: State Dept. to use AI to revoke visas of foreign students who appear “pro-Hamas”. March 6. https://www.axios.com/2025/03/06/state-department-ai-revoke-foreign-student-visas-hamas.

2. National Center for Education Statistics. 2024. “Graduate degree fields.” U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, May. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/ctb/graduate-degree-fields

3. Caputo, Marc. 2025. Scoop: State Dept. to use AI to revoke visas of foreign students who appear “pro-Hamas”. March 6. https://www.axios.com/2025/03/06/state-department-ai-revoke-foreign-student-visas-hamas.

4. Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. 2018. “Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 81, 1–15.” MIT Media Lab, February 4. https://www.media.mit.edu/publications/gender-shades-intersectional-accuracy-disparities-in-commercial-gender-classification/

5. Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. 2023. “Artificial Intelligence, Free Speech, and the First Amendment.” https://www.thefire.org/research-learn/artificial-intelligence-free-speech-and-first-amendment

6. Sap, Maarten, Dallas Card, Saadia Gabriel, Yejin Choi, and Noah A. Smith. 2019. “The Risk of Racial Bias in Hate Speech Detection. Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 1668–1678.” July 28 – August 2. https://maartensap.com/pdfs/sap2019risk.pdf

7. Wischmeyer, Thomas. 2019. “Artificial Intelligence and Transparency: Opening the Black Box. In Regulating Artificial Intelligence, 75–101.” Springer, November 30. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-32361-5_4

8. European Union. n.d. “Art. 22 GDPR – Automated Individual Decision-Making, Including Profiling.” General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). https://gdpr-info.eu/art-22-gdpr/

9. Gedeon, Joseph. 2025. “Mahmoud Khalil: Louisiana Deportation Case Raises Questions About AI Use in Visa Decisions.” The Guardian, March 13. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/mar/13/mahmoud-khalil-louisiana-deportation-case

10. Brown, Cate, Maria Sacchetti, and Shayna Jacobs. 2025. “Trump Administration Targets Pro-Palestinian Activists for Deportation.” The Washington Post, March 12. https://www.washingtonpost.com/immigration/2025/03/12/marco-rubio-mahmoud-khalil-deportation/

11. Parvini, Sarah, Garance Burke, and Jesse Bedayn. 2024. “Surveillance Tech Advances by Biden Could Aid in Trump’s Promised Crackdown on Immigration.” Associated Press, November 26. https://apnews.com/article/artificial-intelligence-ai-deportation-biden-trump-immigration-0a0c2387762a7342af5668660f0391b5.

12. Quinn, Melissa. 2025. “Trump Administration Defends Deportation of Columbia Student Activist Mahmoud Khalil.” CBS News, March 10. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/trump-mahmoud-khalil-ice-columbia-university/

13. Kang, Jay Caspian. 2025. “The Detention of Mahmoud Khalil Is a Flagrant Assault on Free Speech.” The New Yorker, March 13. https://www.newyorker.com/news/fault-lines/the-detention-of-mahmoud-khalil-is-a-flagrant-assault-on-free-speech

14. Immigration Policy Tracking Project. 2025. “Reported: State Department Plans to Use AI to Revoke Visas of Students Engaged in ‘Pro-Hamas’ Activity.” March 6. https://immpolicytracking.org/policies/reported-state-department-plans-to-use-ai-to-revoke-visas-of-students-engaged-in-pro-hamas-activity/

15. NAFSA: Association for International Educators. 2023. “New NAFSA data reveal international student economic contributions continue.” NAFSA, November 13. https://www.nafsa.org/about/about-nafsa/new-nafsa-data-reveal-international-student-economic-contributions-continue.

16. National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. 2020. “Doctorate recipients from U.S. universities: 2020 (NSF 22-300).” National Science Foundation. https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf22300/assets/report/nsf22300-report.pdf

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. Institute of International Education. 2024. “International Students: Enrollment Trends.” Open Doors Report on International Educational Exchange. https://opendoorsdata.org/data/international-students/enrollment-trends/

20. American Immigration Council. 2025. “The H-1B Visa Program and Its Impact on the U.S. Economy.” January 3. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/h1b-visa-program-fact-sheet

21. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2023. “Minister Fraser Launches Canada’s First-Ever Tech Talent Strategy at Collision 2023.” June 27. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/2023/06/minister-fraser-launches-canadas-first-ever-tech-talent-strategy-at-collision-2023.html

22. Federal Office for Migration and Refugees. 2023. “The EU Blue Card.” November 18. https://www.bamf.de/EN/Themen/MigrationAufenthalt/ZuwandererDrittstaaten/Migrathek/BlaueKarteEU/blauekarteeu-node.html

23. National Bureau of Economic Research. 2023. “The Outsize Role of Immigrants in US Innovation.” March 1. https://www.nber.org/digest/20233/outsize-role-immigrants-us-innovation

24. Ibid.

25. Lin, Songyue, Jin Liu, and Wenjing Lyu. 2024. “Who Is More Popular in the Faculty Recruitment of Chinese Elite Universities: Overseas Returnees or Domestic Graduates?” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, October 26. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-024-03818-4

26. Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. 2020. “National Education Policy 2020.” https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf