Introduction

Richard Florida’s article, “The U.S. Cities Winning the Battle Against Brain Drain,” inspired the question of what characteristics that metropolitan areas may have that increase their probability of retaining their university alumni. The article, which Florida wrote for Citylab, a subset of The Atlantic magazine, details which U.S. metropolitan areas are most successful at retaining alumni, or students educated in those metro areas post-graduation. Florida uses research and data from Jonathan Rothwell at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program to inform his findings and allow for a more accurate and nuanced view of which areas do the best job getting young, educated populations to stay. The two main findings from this research was that there was a “moderately high” correlation of 0.48 between alumni retention rates and the size of the metropolitan area. This means that all else equal, larger metro areas do retain young graduates better than smaller metro areas, likely because they offer better job opportunities. On the flip side, the lowest alumni retention rates are often in small college towns that boast prestigious universities. This is not that surprising when one considers that graduates from top tier universities often move to larger cities after they graduate to pursue high skill jobs available there. For example, Ithaca retains about 7% of Cornell’s graduates and the Durham-Chapel Hill metro area retains only 16% of its Duke graduates while Columbia University retains about 53% of its alumni. As a reference point, on average metropolitan areas retain about 30% of its alumni (Florida, 2016).

Florida and Rothwell’s research on the phenomenon colloquially called “brain drain” motivated further research into what other factors could potentially explain some of the variation in alumni retention rates in metropolitan areas. The first factor we examined was how far away students moved to go to college, the variable being distance from home. The assumption behind this was that the closer to home students’ colleges are to their hometowns, the more likely that student is to stay in the metropolitan area after they graduate thanks to strong ties to that area. Our research also examined the potential relationship between unemployment rates and alumni retention. Finally, using U.S. News and World Reports annual “Best Places to Live” report, our research looked to see if those rankings corresponded with alumni retention rates (Florida, 2016).

Implications

Many are interested in what attracts young, educated populations to live in certain cities – and for good reason. Better understanding what factors contribute to the retention of this population could allow local leaders to try and position their metro areas to capture this desirable demographic.

Attracting college graduates to your metro area carries with it many positive externalities. At the most basic level, college educated people often secure better paying, high skill jobs. The elevated earnings from these high skill jobs allows college graduates to spend a little more fueling economic activity in a variety of arenas. As Jonathan Rothwell explains in his Brookings report, individuals with bachelor’s degrees contribute about $270,000 more to local economies than a high school graduate will through spending. Rothwell also finds that local and state taxes are about $45,000 higher for those with bachelor’s degrees (Rothwell, 2015).

Moreover, when examining rates of city growth, many urban theorists point out that cities with higher average levels of educational attainment seem to grow more quickly. These educated cities are believed to benefit from skilled human capital and higher levels of innovation allowing the city to weather economic shocks (Glaeser & Saiz, 2003). As Edward Glaeser, renowned urban scholar explains, there is a “‘strong track record of places that attract talent becoming places of long-term success;’” which is why some argue that the best policy to spur economic development are policies that attract and retain young, educated populations (Glaeser & Saiz, 2003).

Data Sources

There were three main sources of data this project used to try and tease out factors that contribute to alumni retention in metropolitan areas: Jonathan Rothwell, the United States Census and a report from U.S. News and World Reports.

The first source this project turned to was the authors of the Citylab article that started it all – Richard Florida and Jonathan Rothwell. The two of them graciously sent over the raw data that Rothwell had analyzed for their findings last spring. This data gave this project the ability to explore other metropolitan characteristics that could explain the variation in alumni retention. Rothwell and his colleague from the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program, Siddharth Kulkarni, used LinkedIn to gather their data. The researchers gathered information from the profiles of graduates from the largest 1,700 colleges and universities in the United States. The two variables we used from their data collection efforts was the mean percent of alumni who are retained in each metro area, and then we also used their data on the mean geographic distance from student’s home state they went to school. This data spanned 2012-2014 and the analysis was done at the metropolitan level.

This project also employed data from the U.S. Census Bureau to investigate the relationship between alumni retention and unemployment in a metro area. This project relied on data from the American Community Survey, an ongoing survey that provides in depth information on the country than the more basic decennial census collection. Using American FactFinder, the Census’ database, we were able to find data on unemployment rates specifically for Americans with a bachelor’s degree.

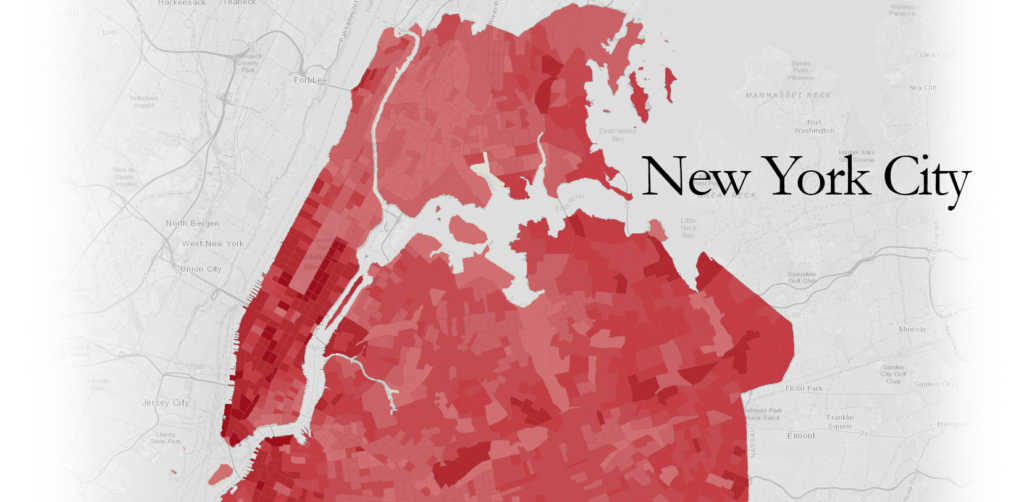

Finally, our last major source of information was a report from US News and World Report’s “Best Places to Live Rankings.” The newspaper analyzed the 100 most populous metropolitan areas and created a scoring system based on five factors. One caveat to this data, the report is from 2016, meaning the scoring occurred two to four years after the rest of this project’s data. However, as this was the first year US News and World Report published this ranking, and because changes to major trends generally occur gradually over a longer period than two years, we felt comfortable using the rankings data anyways. The rankings take into account the strength of a metro area’s job market, affordability, quality of life –measured by among other things well-being surveys and crime rates – desirability statistics using Google Consumer Survey and net migration (2016 Best Places to Live Methodology, 2016). These factors were weighted differently and then compiled to create a raw score for each metro area. This project refers to that raw score as a metro area’s desirability score. This score then allowed us to map the desirability of the country’s top 100 most populous metro areas and compare the result to the data on alumni retention.

Methods

Findings

The strongest relationship we found among the three factors we explored (distance from home, employment status and desirability) and alumni retention was between distance from home and retention rates. When we ran regressions, distance from home had the highest R-value and the steepest slope indicating a relationship of some sort. Though of course this finding in no way indicates causation, there does appear to be a correlation where the closer to home individuals go for college, the higher the alumni retention rate is for that metro area. Perhaps surprisingly, there was a very weak correlation between unemployment rates and alumni retention. One might expect that metro areas with higher unemployment rates for those with bachelor’s degrees would have difficulty retaining alumni. Our analysis, however, shows that the relationship in fact appears to be the opposite, so higher unemployment rates are also correlated to higher retention rates. One possible explanation for this unexpected finding is that retention as a whole is higher for more populous cities, and perhaps larger cities have higher unemployment rates. The last major finding of this project was also somewhat unexpected: desirability of location appears to have no relationship with alumni retention.

Here, we combined the Desirability Rankings of these cities with the Alumni Retention ability. Alumni Retention was showed as a percentage instead of by standard deviation, just to give a better glimpse of the patterns in those particular areas. The classification was done as Jenks. This was done because it minimizes the variance within the groups while maximizing the variance between the groups. It identifies break points in. The second group showed a patch in the Midwest (around Ohio and Illinois) that had pretty average rankings but great retention rates. The other was in Texas, where there were great rankings and still high retention ability. These areas were chosen because of having several similar metropolitan areas close to one another.

Because the retention ability versus desirability ranking didn’t explain the patterns seen in the Midwest, we decided to check out another powerful variable that we had access to- distance from home. It can be seen that these alumni didn’t stray far from home, from the most part. Distance and Alumni Retention were classified using Jenks because of its ability to find natural breaks in the data.

Conclusion

As with many research endeavors, this project raises more questions than it answers. It is clear that it is in the best interest of metropolitan areas to attract and retain young, educated populations. How leaders and policy makers should go about this goal though is certainly up for debate. Many of the factors that make up an area’s desirability score (for example access to education and cost of living) are factors that can actually be impacted by policy decisions. However, since this project found no relationship between a metro area’s desirability score and the area’s ability to retain alumni, it is not clear what policy would be in the best interest of metro areas. Furthermore, unemployment is almost always considered a negative, however in this project it was correlated with higher retention of alumni. As previously stated, this is by no means a causal relationship, but it does raise further questions about what factors are truly behind this apparent (weak) relationship. The factor that appeared to best explain retention was distance from home of students’ college, which perhaps suggests metro areas should invest in state colleges and universities which naturally attract more local students if they want those same students to stay in the metro area after they graduate too. It is certainly interesting to think closely about what pushes people to live in the areas they do, however, in terms of being able to suggest actual solutions for metro areas to retain alumni, this research topic needs a great deal more investigation. As of now, it appears that there are few levers for policy makers to pull if they want to keep skilled, educated and young populations in their metro areas.

2016 Best Places to Live Methodology. (2016). Retrieved December 4, 2016, from U.S. News and World Reports: http://realestate.usnews.com/places/methodology

Florida, R. (2016, March 15). The U.S. Cities Winning the Battle Against Brain Drain. The Atlantic.

Glaeser, E. L., & Saiz, A. (2003). The Rise of the Skilled City.

Miller, C. C. (2014, October 20). Where Young College Graduates Are Choosing to Live. The New York Times.

Rothwell, J. (2015). What colleges do for local economies: A direct meaure based on consumption. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

United States Census Bureau. (n.d.). Metropolitan and Micropolitan. Retrieved December 5, 2016, from United States Census Bureau: https://www.census.gov/population/metro/