Written by: William LaRose

Edited by: Adam Terragnoli

Introduction: The Global War on Terror

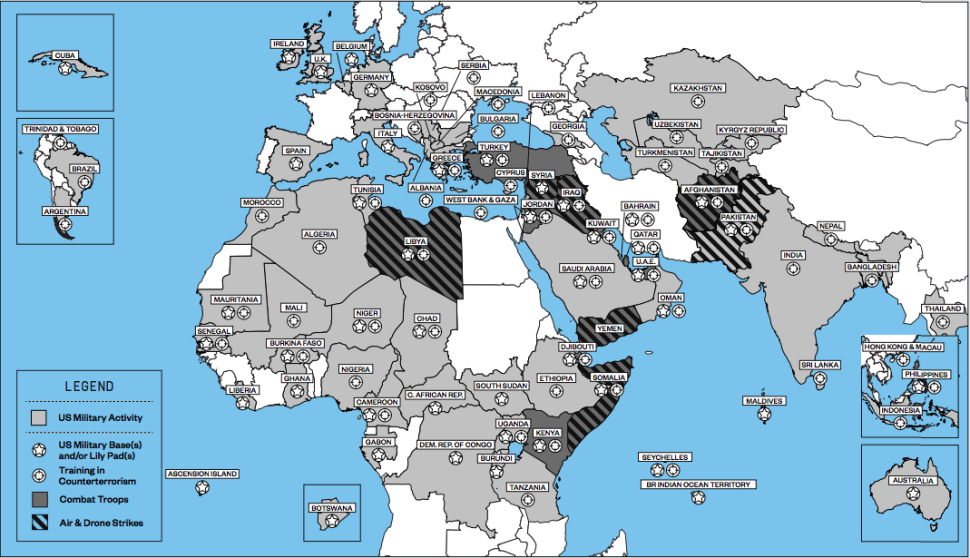

On October 4th, 2017, militants from the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara ambushed a joint patrol of Nigerien and U.S. soldiers outside the village of Tongo Tongo.1 Resulting in the largest loss of American lives during combat in Africa since 1993, this event prompted concerns from both the public and the U.S. Congress about the military’s role in Western Africa.2 The Department of Defense revealed that 800 troops were stationed in Niger, with more than 6,000 soldiers spread across fifty-three nations in Africa, most of whom were “assisting local forces against the threat of ISIS.”3 With the Global War on Terror approaching its nineteenth year, the U.S. military’s counter-terrorism efforts involve thirty-nine percent of the world’s countries.4 As these conflicts become increasingly visible to the public, many Americans have begun to question how and why U.S. military forces have spread so quickly beyond Iraq and Afghanistan.

The Current United States Counterterror War Locations (The Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University, 2018)

History of War Powers in the United States

In Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution, Congress retains the sole ability to declare war and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.5 Additionally, in Article 2, Section 2, the President is granted the role as Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States.6 Simply put, Congress has the power to declare war, the President has the power to wage it. Over the course of history, Congress has formally declared war on eleven occasions, first with Great Britain in 1812 and lastly at the onset of World War II in 1942.7

However, as the U.S. moved from conventional conflicts into the Cold War era, an interesting phenomenon began to emerge. A number of presidents began to circumvent Congress and deploy American forces abroad, justifying their military engagements as everything from “police action” in Korea to “military advisors” in Vietnam.8 A debate over who had the Constitutional power to declare war divided the country into two factions. As the Congressional Research Service notes:

“The congressional view was that the framers of the Constitution gave Congress the power to declare war, meaning the ultimate decision whether or not to enter a war. Most Members of Congress agreed that the President as Commander in Chief had power to lead the U.S. forces once the decision to wage war had been made, to defend the nation against attack, and perhaps in some instances to take other action such as rescuing American citizens. But, in this view, he did not have the power to commit armed forces to war.”9

The continued shift in power to the executive branch was counteracted by a joint resolution passed by Congress in 1973. Known as the War Powers Resolution, this new law has since required that the President report to Congress any introduction of U.S. forces into hostilities, that the use of force must be terminated within sixty to ninety days unless Congress extends the time period, and that the “President in every possible instance shall consult with Congress before introducing” U.S. Armed Forces into hostilities.10

President Nixon argued that this joint resolution, in effect, stripped away authorities the President “has properly exercised under the Constitution for almost 200 years.” 11 Over the coming decades, Nixon would not be the only President to criticize or outright challenge the War Powers Resolution. From Reagan’s use of troops in El Salvador, to Clinton’s bombing campaign in Kosovo that surpassed sixty days, many Presidents have continued to find creative ways to circumvent the law and Congress. In the modern era, the Authorization for the Use of Military Force is one such method of circumnavigation.

Authorization for the Use of Military Force

The Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) was passed by Congress in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. This joint resolution granted the President the authority to use “all necessary and appropriate force” against those nations, organizations, or persons he determined “planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks.”12 While originally meant to allow the President to act judiciously in the fight against those responsible for the attacks on September 11th, it has since been used to justify military action in conflicts as wide ranging as Yemen and Libya. In September of 2014, a senior administration official in the Obama administration wrote that the President may rely on the 2001 AUMF as “statutory authority” for the use of force against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.13 The same logic was used to jumpstart a campaign of drone and air strikes against ISIL in Libya nearly a year later.14

In response to these actions, the sixty short words of the AUMF have been painted as everything from not going far enough, to a mechanism for “eroding congressional war powers,”15 to “the most dangerous sentence in U.S. history.”16 Regardless of one’s stance, it is clear the patterns seen during President Obama’s years in office have continued with the Trump administration. From North Africa to Yemen, the steady increase in military action using the AUMF as legal authority has been staggering. Whether authorizing seventy-five drone strikes in his first seventy-four days in office17, moving additional military power into Niger18, or conducting extensive operations in Syria, President Trump has followed Obama’s lead with respect to AUMF.

Most recently, issues surrounding AUMF have emerged as tensions heat up with Iran. In a hearing in April of this year, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that Al-Qaeda operates within their borders, saying “There is no doubt there is a connection between the Islamic Republic of Iran and al-Qaeda. Period. Full stop.”19 Some believe such a connection may allow the White House to confront Iran militarily without Congressional approval through the AUMF.20 Whatever the case may be, a number of alternatives to the current AUMF can be explored.

Policy Alternatives

The current debate regarding the AUMF is divided into two camps: those that argue the current AUMF too drastically limits the President’s power, and those that claim it gives the President a blank check to wage war. It is clear that any debate about how to move forward with the AUMF should be taken up by Congress. Steve Vladeck and Tess Bridgeman of the Cato Institute suggest repealing the AUMF altogether. Following a sunset period of six to nine months, after which the AUMF would expire, they argue that the President would need to make the case for any new authorization to Congress.21 Other bipartisan bills from Congress propose sunset periods that range from three to five years, with broad language that includes “associated forces” which is a provision that allows the President to expand the target list at will.22

Sen. Jeff Merkley’s proposed AUMF bill would limit the use of force to Iraq and Afghanistan, and to Al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and ISIS. Additionally, “the countries and targets must be published and cannot be classified; and for the most part, it requires the President to come to Congress to add new countries and new groups.” 23 Finally, Alice Friend of the Center for Strategic and International Studies suggests that Congress might consider a threat-based authorization, on a case-by-case basis. Friend argues that any proposal for new deployments would have to pose a direct threat to the U.S., its allies, or partners, and the President would be required to provide assessments every six months once combat forces are deployed.24

As the U.S. examines its foreign policy and place in the world, a renewed debate regarding the AUMF in Congress is essential. With Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution in mind, a steadfast commitment to Congress’s power to declare war should be reaffirmed in any discussion. Future conflicts should be clearly defined, follow the delineated powers of the Constitution, and proceed with increased transparency. As James Madison, founding father and fourth President of the U.S. noted in 1793, “The power to declare war, including the power of judging the causes of war, is fully and exclusively vested in the legislature… the executive has no right, in any case, to decide the question, whether there is or is not cause for declaring war.”25 As the Global War on Terror approaches its nineteenth year, it is time to return the power to declare war to Congress and reconsider the Authorization for Use of Military Force.