By: Sebastián Restrepo

Edited by: Andrew Bongiovanni

Graphic by: Arsh Naseer

“In five years, the five years that have just passed, our government has always opted for the narrow path as the Bible says; we never took the broad, easy way out. The challenges, therefore, were greater than any of us could have imagined. However, God’s mercy was also greater for us, and little by little, we began to create something much more significant. A mirror where all of Latin America now sees itself.”1

This is a section from the inauguration speech that the re-elected President of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, gave on his presidential investiture on June 1, 2024. El Salvador is the smallest country in Central America, with an area of 8,124 mi2 (smaller than the State of New Jersey) and a population of just over 6 million. El Salvador does not even represent 1% of the population or the area of Latin America. However, this country is disrupting discussions about democracy and security in Latin America since Bukele’s reelection represents his authoritarian regime and a critical juncture for Latin America. El Salvador is becoming a mirror where all Latin America is starting to see itself.

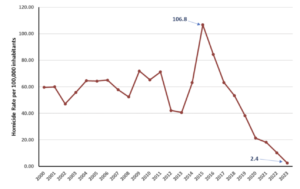

Bukele is recognized throughout the region mainly because of his security results and his high popularity among Salvadorans. During his first presidential term campaign in 2019, one of Bukele’s central promises was to reduce violence in El Salvador, disbanding Las Maras, particularly The Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and the Mara Barrio 18 (18thStreet Gang), a terrorist organization of criminal gangs.2 He fulfilled that promise, lowering the homicide rate from the highest in the region to the lowest in the Americas (view Chart 1.) He accomplished this while also having a popularity rating of 92%.3

Chart 1. Homicide Rate in El Salvador, 2000-2023

Source: World Bank (2024)4

However, this achievement is accompanied by criticism from academics, the press, and international organizations that Bukele’s mandate is no longer democratic and has become an authoritarian regime. Bukele follows a new authoritarian model that several scholars have studied recently.5,6,7 The resistance to pointing out that Bukele is an authoritarian lies in the fact that his rise to power did not come from military coups. Instead, Bukele is a more sophisticated authoritarian, appearing to be an outsider who seeks to fix the problems of democracy from within, competing and winning elections, and addressing the main problems of the subset of the public he represents. Human Rights Watch has warned about antidemocratic practices in El Salvador, including the coercion of the Salvadoran Judicial Branch, an extended State of Exception since March 2022 (for more than 25 consecutive times), the implementation of an imprisonment policy antithetical to due process, torture, harassment against journalist and civil society organizations, and poor accountability for human rights violations.8 Nevertheless, Bukele has delivered what he promised, as demonstrated by the results in security and his high popularity. Thus, it begs the question: why should the criticisms of him be taken as valid if it has not been demonstrated that anything he has done has violated the constitutional framework of El Salvador?

After the inauguration of his second term, Tucker Carlson, a recognized U.S. conservative pundit, interviewed Bukele. In this interview, Bukele mentioned how he achieved a super-majority in Congress, that Congress replaced the Supreme Court Justices and the Attorney General, and that the only institution he still does not control is the Electoral Tribunal. At that moment, Carlson interrupts him and asks: “But you stay within the rules the whole time,”9 Bukele responds:

“We have never not respected a single rule. That is also a narrative that they want to produce. They cannot point out a single thing that was done by not respecting the rules that were written by them. Because the rules are written by people, it is not like these rules were, you know, given by God. These rules were written by people, but still we respected all the rules that were written by them.”10

Still, Bukele did violate the Salvadoran Constitution. As Jorge Sabasta explains, the Constitution of El Salvador prohibits immediate reelection.11,12 Bukele presented himself as a candidate under a legal interpretation that goes against the “spirit of the law,” where the restriction of reelection seeks to prevent the perpetuation in power of any person. Beyond agreeing or not with the figure of reelection in a country, it is necessary to respect the existing rules of the game and not to interpret them according to individual benefit. In the words of Philippe C. Schmitter and Terry Lynn Karl:

“The defining components of democracy are necessarily abstract, and may give rise to a considerable variety of institutions and subtypes of democracy. For democracy to thrive, however, specific procedural norms must be followed and civic rights must be respected. Any polity that fails to impose such restrictions upon itself, that fails to follow the ‘rule of law’ with regard to its own procedures, should not be considered democratic. These procedures alone do not define democracy, but their presence is indispensable to its persistence. In essence, they are necessary but not sufficient conditions for its existence.”13

James Mahoney and Kathleen Thelen define a “critical juncture” as an opportunity that appears when the restrictions of stable institutions disappear for a period of contingency and an agent decides to change the course of a society’s development.14 Michael Bernhard defines a juncture as “critical” if the effects of those actions echo in the long term, generating path dependency.15 Bukele’s reelection is a critical juncture that started with his cooptation of power and, as a domino effect, will have repercussions throughout Latin America.

Hillel David Soifer proposed seven steps to identify and describe a critical juncture, and Bukele’s reelection fulfilled this characterization.16 (1) Identification of the permissive condition: Bukele’s extraordinarily high popularity in his country was the permissive condition. (2) The identification of productive conditions: In El Salvador’s case, it was the change of interpretation of the Constitution. (3) The critical antecedent: In the case of El Salvador’s elections, the critical antecedents may include the renewal on 25 occasions of the State of Exception and the changes in the Congress (where the number of congressmen was reduced from 84 to 60). (4) The outcome: This is evinced by Bukele’s (unconstitutional) reelection. (5) The end of the critical juncture: This occurs when Bukele’s popularity fades away; this happens when an economic deterioration occurs or when repression is even more extensive than it has been until today. (6) The mechanisms of reproduction: In this case, the mechanism is the continuation of the State of Exception renewal to apply Bukele’s policies. (7) Consequences: This would be Salvadoran democracy’s continuous deterioration, and a greater intensity in the desire to replicate Bukele’s model in other Latin American countries.

Despite the dangers facing democracy in the long run, the temptation for other Latin American countries to copy Bukele’s model is as high as his popularity.17 Several political leaders from countries in the region, such as Chile, Colombia, Panama, Uruguay, and Mexico, have expressed their desire to replicate Bukele’s security model.18 Considering only the security variable, there is no shortage of reasons to emulate Bukele’s model in the region, such as the cases of Ecuador and Haiti, where the homicide rate quadrupled in less than two years, reaching more than 40 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants. As Salvador Martí and Daniel Rodríguez synthesize it:

“Without this more than striking decrease in homicides in the country, Bukele might not have won. The question, however, is the extent to which, at the expense of citizen security, he has been allowed to advance rapidly in a process of institutional, democratic, and human rights deterioration, which has meant the concentration of power in his figure.”19

Bukele’s presence in the region interrogates whether it is possible to speak of democracy without minimum security conditions. The challenge of terrorism that Bukele faced was not negligible20; no citizen in any part of the world should face the dilemma of choosing peace or democracy. Bukele’s challenge now is to build a democratic model that responds to the voices of those who point to him as authoritarian without losing the achievements made regarding security.

To conclude his presidential inauguration speech, Bukele asked, from the presidential balcony, that everyone raise their hand and repeat the following oath: “we swear to defend our Nation project unconditionally, go by the book, without complaining, asking for God’s wisdom, so that our country will be blessed again with another miracle. And we swear never to listen to the enemies of the people.”21 Several questions arise from this oath: Who are the people? Who are the opponents? Who defines who the people are and who the opponents are? How can democracy exist if they swear not to listen to their opponents? The “Bukele effect” seems to generate authoritarian echoes in Latin America with the excuse of having a safer region and hoping to replicate the same image seen in El Salvador’s mirror.

Works Cited

[1] Bukele, N. 2024. “Investidura Presidencial [Presidential Investiture]” [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1qFnW-unETo&t=5979s.

[2] Bukele, N. 2022. Cómo estamos logrando la victoria… [How we are achieving the victory…] [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i8ATZWmPa_Q.

[3] CID Gallup. 2024. Presentamos resultados de nuestra última encuesta realizada en mayo, 2024. Aprobación de la Gestión Presidencial. [We present the results of our latest survey, conducted in May 2024. Approval of Presidential Administration.] [Photograph]. https://www.instagram.com/p/C8DXTuARfg_/.

[4] World Bank. 2024. Homicide Rate in El Salvador, 2000-2023. https://www.worldbank.org/.

[5] Snyder, T. 2017. On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century. New York: Crown Publishers.

[6] Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. 2018. How Democracies Die. New York: Crown Publishing.

[7] HRW. 2024. El Salvador. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/americas/el-salvador.

[8] HRW. 2024. El Salvador.

[9] Carlson, Tucker. 2024. Bukele: Seeking God’s Wisdom, Taking Down MS-13, Advice to Trump [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U5n8R9lq8SI.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Sabasta, J. 2024. Nueva victoria de Bukele en El Salvador [New Bukele victory in El Salvador]. Journal de Ciencias Sociales 1(22). https://doi-org.proxy.library.cornell.edu/10.18682/jcs.v1i22.10958.

[12] Const. 1983. Constitution of the Republic of El Salvador, Articles 78, 88, 152, 154. July 29th, 1983 (El Salvador).

[13] Schmitter, P. C., & Karl, T. 1991. What democracy is.. and is not. Journal of Democracy 2(3): 75-88.

[14] Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (Eds.). 2009. A Theory of Gradual Institutional Change. In Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency, and Power (pp. 1–37). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[15] Bernhard, M. 2015. Chronic Instability and the Limits of Path Dependence. Perspectives on Politics 13(4): 976–991. doi:10.1017/S1537592715002261.

[16] Soifer, H. D. 2012. The causal logic of critical junctures. Comparative political studies 45(12): 1572-1597.

[17] Dämmert, L. 2023. “El «modelo bukele» y los desafíos latinoamericanos” [The “Bukele model” and Latin American challenges]. Nueva Sociedad, (308), pp. 4-15. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/el-modelo-bukele-y-los-desafíos-latinoamericanos/docview/2906427267/se-2.

[18] Budasoff, E., & Viñas, S. (Hosts). 2024. Después de Bukele [After Bukele]. [Audio podcast episode]. In Bukele: El señor de los sueños. [Bukele: The lord of dreams.] Central. Radio Ambulante Studios. https://centralpodcast.audio/episodio-extra-bukele-segundo-gobierno/.

[19] Martí Puig, S., & Rodríguez Suárez, D. 2024. Nayib Bukele, seguridad a cambio de democracia [Nayib Bukele, security in exchange for democracy]. Más Poder Local (56): 141-154. https://doi.org/10.56151/maspoderlocal.231.

[20] Chavez, Y. 2024. Bukele’s Formula for Terrorism. Journal of Strategic Security 17(1): 76-99. https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.17.1.2186.

[21] Bukele, N. 2024. “Investidura Presidencial [Presidential Investiture].”