Image Source: http://www.globalgoals.org/

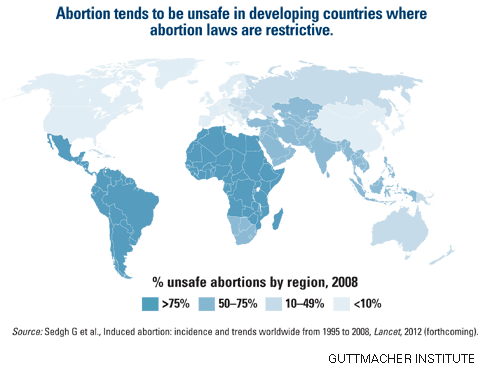

Data from the World Health Organization estimates that 21.6 million women experience an unsafe abortion each year. An overwhelming 85% of these abortions occur in developing countries and 13% of all maternal deaths in the world are due to unsafe abortions. In September 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were approved and are now shaping the future of development as well as sustainability; therefore, these goals must be critically analyzed to ensure the enhancement of maternal healthcare. Target 3.7 of the SDGs states “By 2030, ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare services including family planning, information and education as well as the integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programs.” An issue of contention is whether the language adopted by this SDG target supports safe abortion across the world. This begs the question of the goal’s feasibility in developing countries, considering the social prominence of pro-life advocates.

As the world transitions from the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to the newly introduced SDGs for 2030, there are many lessons to be learned regarding the betterment of women’s sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR). One of the most important issues at hand is the SDGs’ commitment to achieving universal access to SRHR as stated by Target 3.7. The ambiguity of this target inherently suggests that SDGs support liberal abortion policies since they are an integral part of SRHR. The new SDGs’ preamble clearly states, “As we embark on this collective journey, we pledge that no one will be left behind.” The word “collective” stands out as it reinstates the importance of inclusivity for all. However, it can be argued that the gaps created by the vagueness of SDGs in relation to abortion policies do not enhance this collective framework. Instead they are a stark reminder of the MDGs weaknesses in leaving behind those who do not have access to safe abortion services. Though one of the MDGs’ target was to reduce maternal mortality and achieve universal access to reproductive health, like the new SDG target 3.7, nothing in its framework specified the prevention of unsafe abortions.

Pro-life advocates warn that SDG’s promotion of “universal access” and “SRHR” spell out access to safe abortion, arguing that the implementation of these goals will lead to an expansion of abortion and contraception especially in the developing world. Despite this, the Vatican supported the “coordination of all sources of financing to achieve the SDGs.” The backing from the Vatican comes as a surprise because the Catholic Church is a known adamant supporter of the pro-life movement. Some pro-choice advocates have also argued since the SDGs are too vague in their language they are not progressive in effect. According to Rep. Chris Smith, the ambiguity of the text can easily be interpreted to include abortion, which may result in pro-life donors not supporting development funding on maternal healthcare.

Although they do encompass important matters such as family planning and comprehensive sex education, SDGs do not explicitly talk about safe abortion. Ann Starrs, President and CEO of the Guttmacher institute (the former research arm of Planned Parenthood), argues that though the SDGs are comprehensive and visionary, they take a narrow view of SRHR. According to her, they in fact do not clearly “articulate a progressive and evidence-based vision on how to move forward on SRHR.” This explains her work to support the implementation of a new commission, beyond the SDGs, that will promote access to safe abortion. Indeed, this new commission is basing its justifications on evidence suggesting that safe abortion laws are the way to go. Considering that a 2013 United Nations Secretary-General identified unsafe abortions as a “leading cause” of maternal deaths, the SDGs’ 2030 target to reduce maternal mortality by two-thirds is therefore impossible if the issue of safe abortions is not addressed properly. A global review of key interventions related to reproductive and maternal health recognizes that access to safe and legal abortion is an essential component of comprehensive SRHR services and should ideally be available to all women regardless of age, race, religion, geographic location, ethnicity, or migration status.

Though abortion is clearly a sensitive topic that traverses boundaries of culture and religion, policy makers, especially in developing countries, will have to make difficult decisions. Policy changes in South Africa are a practical example of how liberalizing abortion policies may actually improve maternal healthcare. Since the passing of The South African Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act (CTOP) in 1996, abortion-related mortality is estimated to have declined by 91.1% from 1994 – 2001. The CTOP Act allows for termination of pregnancy up to 20 weeks of gestation, thus encouraging women to have early, safe, and legal abortions. Similar results were noticed in the United States after the nationwide legalization of abortion in 1973: complications and deaths due to unsafe abortions ended within a short period of time.

Despite liberal laws, abortion-related stigma in less developed countries often causes women to seek abortions outside of the legal system. The reality is that most of the barriers to progress that inhibited the better implementation of MDG 5 in developing countries—such as weak health systems, poor access to services, and gender inequalities—still lurk in the SDG era and will without a doubt also impede the achievement of SDG target 3.7. According to a 2009 South African government survey, only 25% of registered community health centers in South Africa were offering abortion services. The case is similar for Zambia. Although abortion has been legal in Zambia since 1994, the cost of performing abortion is still prohibitive, and many doctors do not perform abortions because of their moral beliefs. Similarly, though India has authorized abortion for over three decades, poor physician training and high private-sector prices still contribute to unsafe abortion practices, as women seek affordable services in public health facilities that offer low quality care. These examples indicate that perhaps there lies a deeper solution to improving maternal healthcare than liberalizing abortion policies in less developed countries. The lack of clarity in the SDG target 3.7 does not address these deeper issues hence leaving no room for improvement and hence no significant change from the MDG era.

Intense negotiations have to be addressed sooner rather than later in order to find the best solution for moving forward. The challenges of MDG 5 demonstrate how the SRHR of many women and girls are compromised by the stigma and political controversy surrounding abortion practices. Policies that criminalize abortion in developing countries deny women control over their own reproductive decisions, and this lack of control in turn impedes their equal participation in their nations’ social, political, and economic activities. Essentially, if these policies are not revised at the international level and personalized at the national level, the SDGs will not catalyze the improvement of maternal healthcare by 2030, and instead there will be a repetition of the MDGs’ weaknesses. The lack of clarity in the SDGs’ targets may again hinder implementation of safe and legal abortion procedures for women in high-risk countries, which essentially puts many women at risk of maternal morbidity and mortality. Is this a price the world is willing to pay again?