By: Celia Doherty

Edited by: Andrew Bongiovanni

Graphic by: Arsh Naseer

“Inter-Malian dialogue” began in Bamako this May, facilitated by Interim President Assimi Goita and the military junta who seized power in August 2021 after back-to-back coups. Opposition groups criticized the process as a “sham.”1 With the purported aim of “reconciling the sons and daughters of the country and establishing lasting peace,”2 where did these negotiations fall short, and how might a shift in security policy play out?

Mali’s current situation is unsustainable and violent. Civilians face increasing danger from multiple angles. Amidst a crisis of jihadist violence across the Sahel, non-state armed groups, including Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), have made great territorial gains in northern Mali and intensified violence in central regions, particularly Mopti. A January 2022 partnership between the Armed Forces of Mali (FAMA) and the Kremlin-associated Wagner Group has contributed to an increase in extrajudicial violence against civilians, with little progress towards the stated goal of pushing out extremists. Drought and extreme weather intensify food insecurity and strain aid systems; as of 2022, 412,000 Malians were internally displaced and in 2023, an estimated 8.8 million people needed humanitarian assistance.3

Faced with these mounting issues, national and international bodies have largely stayed the course on militaristic and security-based policies that aim to defeat and contain armed groups. The French-led Operation Barkhane lasted for almost a decade after troops arrived in 2012 to drive back a jihadist insurgency following a military coup. Yet despite many years in the region and an operating budget of almost €600 million annually,4 French presence failed to provide lasting security and the situation remains at an impasse. Neither the government nor militant groups appear the likely victor. Growing anti-French sentiment stems from claims that the French limited Malian agency and dictated security policy, including discouragement of any negotiations with armed groups.

Even before the military junta demanded the withdrawal of French troops in February 2022, numerous opportunities for dialogue arose. The idea gained traction in 2016 before French pressure sidelined further action.5 A 2020 prisoner exchange with JNIM created a precedent for channels of communication with jihadist leaders.6 Aliou Nouhoum Diallo, the former speaker of parliament, has advocated on occasion for informal communication with jihadists as an entry step for state-sponsored dialogue.7 Notably, leaders from JNIM, who seek to dismantle regional governments they view as puppets of the West, have made statements suggesting their openness to the idea.8 The disconnect between the government’s top-down approach and successful but isolated community-negotiated peace compromises Mali’s territorial integrity and erodes hope of building a framework for democratic governance down the road.

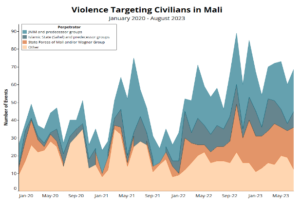

Source: ACLED (2023)9

Critics claim the national dialogue was an attempt by Goita to remain in power. Discussions concluded the junta should extend its control for several more years and presented Goita as a potential future candidate. Numerous opposition groups voiced their disapproval. Despite mixed reactions to delays of a promised transition to civilian rule, envisioning elections as a quick-fix antidote to democratic erosion and the security crisis bypasses several critical steps in state building. Holding an election to establish a democracy in name only does not adequately address pressing security issues and continued government failure to meet the needs of its citizens. Ken Opalo, Associate Professor at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, argues that Mali must focus on the “fundamentals of establishing order and a serious rebuilding of the foundations of democratic self-government.”10 Once these are in place, introducing elections has greater potential to produce democratic outcomes. The cyclical violence produced by the “defeat and contain” policy has not yielded consistent results and has fractured trust between government and citizens. A pivot towards state-supported dialogue is a beginning, but successful implementation of such a policy rests on the degree to which community leaders and jihadists are involved. Negotiations support solutions to localized conflicts where a more centralized and coercive state can begin to take shape and rehabilitate lost legitimacy.

Opportunities for Improved Security and Democratic Foundation

Legitimize the Government

Local “survival pacts,” initiated by communities who make large concessions in the name of peace, suggest a willingness by Malians impacted by conflict to negotiate with armed groups.11 In a December 2020 interview, Moctar Ouane, Mali’s transitional Prime Minister, called dialogue with terrorists “the will of the people of Mali,” underscoring an openness to use dialogue to combat extremism.12 An influential imam, Mahmoud Dicko, has continued to plead for dialogue with jihadist leaders. However, France’s strong posture against discussions limited Mali’s agency to explore this avenue in the past.13 French President Emmanuel Macron stated that France would not “carry out joint operations with powers who decide to discuss with groups who…shoot our children.”14 Adherence to a Western framework fueled anti-incumbent sentiment and de-legitimized the government, seen as too close to a former colonizing power. The former deputy chief of staff during Operation Barkhane acknowledged, “we acted like a big brother who would turn to his little brother and tell him what to do and not do. We’ve been the know-it-all trying to apply templates that weren’t suited to them.”15 Pursuing negotiations with jihadists may enhance government legitimacy and rebuild their damaged reputation, portraying them as more receptive to the will of the people and autonomous in decision-making free from Western influence.

Stem the flow of extremist recruitment

Militaristic policies reducing the conflict to the actions of jihadist groups overlook the nuance of the problem; violent groups are often driven by political, not ideological, demands. A closer look at the motivations behind joining jihadist groups indicates that a military-driven response will remain ineffective as long as root issues persist unresolved. A 2016 Institute for Security Studies report interviewing former members of Malian jihadist organizations observed a variety of motivations for joining, spanning “personal, economic, political, religious, familial, educational, social welfare, ethical [and] influence-based,” concluding that the “idea that young people join armed groups because they adhere to radical religious ideologies is therefore a misconception that could lead to inappropriate responses.”16 Opalo warns against superimposing globalized ideologies on people fighting over land.17

The plethora of political motivations spanning the hierarchy of armed groups proffers an opportunity to resolve local discord, disband armed actors, and undermine the recruitment and retention success of organizations whose membership is not a product of extreme ideology. A militaristic approach to armed groups has not only failed to address political concerns, but has exacerbated them. Civilians are targeted by both militant organizations and FAMA based on perceived alliances or support of various groups, contributing to the 38 percent increase in civilian targeting in 2023.18 Jihadists often capitalize on discontent with government services, or a lack thereof, when recruiting citizens. A decreased reliance on military action releases funds to strengthen underfunded social services like healthcare and education. This infrastructural weakness deeply impacts Malian youth who lack economic mobility and opportunity, thus becoming a prime demographic for jihadist recruitment. Openness to diplomacy and dialogue demonstrates a willingness to address local grievances from armed civilian groups or paramilitary forces, confronting perceptions of a disengaged and dispassionate government and weakening a primary recruitment strategy of jihadists.

Increase Civil Society Participation and Engagement

The top-down approach from the government and the bottom-up approach from local populations both have drawbacks. Malian leaders have sought out Amadou Kouffa, a preacher turned leader of the Katibat Macina militant Islamist group, and Iyad Ag Ghaly, a leader of JNIM, while relying on religious authorities from the High Islamic Council of Mali.19 Their neglect of traditional community and religious leaders, youth, and others involved in conflict overlooks the regionally specific motivations for high community recruitment into extremist organizations. The 1991 National Conference, hailed by Malians as a triumphant moment for democracy, offers a blueprint for successful dialogue and found success in including a wide range of backgrounds.20 The 2015 Algiers Accord, a past attempt at negotiation, fell short by failing to engage Malians at the community level. These leaders act as invaluable conduits for persuasion between the state and jihadists.21

In some regions, particularly in central Mali, communities have taken negotiation into their own hands. Local populations have entered into agreements with jihadist groups to secure small ceasefires, access to farming and fishing, the reopening of schools, food supplies, access to humanitarian assistance, and de-escalation of resource-related conflict.22 In exchange, violent groups have, in some areas, demanded a return to Sharia law and refused entry to the Malian army. Such tactics, successful in their pragmatism, fail to provide a broader, long-term solution and compromise the territorial integrity of Mali. A good-faith effort by the government to mirror the successful elements of the bottom-up appeal initiated by their citizens, or simply providing material support to facilitate dialogue, may rebuild a broken trust between politicians and communities. Local leaders believe that their network of contacts and information––a byproduct of their dialogue––would give the government a “head start.”23 A 2017 survey found that 55.8 percent of Malians supported dialogue with jihadist groups, further affirming the desire on the ground for an altered policy approach.24 Inviting community leaders to shape a national policy offers a possibility to inspire greater civil society participation and input in the political process, a positive trend to establish democratic foundations.

Looking Ahead

Goita claimed national dialogue was “entirely inclusive,”25 but the preeminence of short-term military policies, and the exclusion of localized voices and jihadists, limits the potential efficacy of peacebuilding attempts. Negotiation is not a new idea, but its sporadic and narrow implementation by Mali’s authorities has muted any potential payoff. Meanwhile, local agreements continue to form and function, with varying degrees of success. As survival pacts proceed largely unaddressed by the Malian government, trust in a social contract diminishes and provides fodder to the same arguments justifying the last military coup––a deteriorating security situation and an unwillingness to respond adequately to the demands of their citizens. Another coup would threaten to create a power vacuum and further delay hopes of democratization efforts.

A comprehensive overhaul of any military-driven policy is unrealistic; security options remain important in the ongoing counterinsurgency efforts. The outcomes of any negotiations are not guaranteed and indeed, may fail. Short-term efforts paired with enhanced dialogue tactics undoubtedly face obstacles, including questions on capitulation to terrorists and the preservation of the secular nature of Mali’s constitution. The risk of conditional aid from international actors adds complication, but a desire to buffer Mali’s developing ties with Russia may incentivize French and US authorities to respect the path chosen by Mali rather than attempt to dictate terms of engagement.26 Revisiting burgeoning policy around dialogue, backed by popular support, could redefine success in Mali’s conflict resolution and state-building efforts, limit further atrocities against civilians, and lay the groundwork for a more engaged citizenry and legitimate governance.

Works Cited

[1] Voice of Africa.”Mali Opposition Rejects Results of ‘National Dialogue’.” Accessed June 6, 2024. https://www.voaafrica.com/a/mali-opposition-rejects-results-of-national-dialogue-/7608880.html.

[2] Atlas of Wars. 2024. “Inter-Malian Dialogue: A Way to Delay Elections?” Atlas of Wars (blog), May 7. https://www.atlasofwars.com/inter-malian-dialogue-a-way-to-delay-elections/.

[3] U.S. Agency for International Development. 2024. “Mali | Humanitarian Assistance,” May 3. https://www.usaid.gov/humanitarian-assistance/mali.

[4] European Council on Foreign Relations. Accessed June 14, 2024. “Operation Barkhane – Mapping Armed Groups in Mali and the Sahel.” https://ecfr.eu/special/sahel_mapping/operation_barkhane.

[5] Le Monde. 2020. “Au Mali, Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta Assume Un Dialogue Avec Les Djihadistes,” February 12. https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2020/02/12/sahel-le-president-malien-assume-un-dialogue-avec-les-djihadistes_6029246_3212.html.

[6] BBC News. 2020. “Mali Hostages: Sophie Pétronin and Soumaïla Cissé Freed in Prisoner Swap,” October 8. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-54472504.

[7] War on the Rocks. 2020. “France Should Give Mali Space to Negotiate with Jihadists,” April 16. https://warontherocks.com/2020/04/france-should-give-mali-space-to-negotiate-with-jihadists/.

[8] The New Humanitarian. 2022. “‘We Accept to Save Our Lives’: How Local Dialogues with Jihadists Took Root in Mali,” May 4. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/2022/05/04/we-accept-save-our-lives-how-local-dialogues-jihadists-took-root-mali.

[9] Nsaibia, Héni. 2023. “Fact Sheet: Attacks on Civilians Spike in Mali as Security Deteriorates Across the Sahel.” ACLED (blog), September 21. https://acleddata.com/2023/09/21/fact-sheet-attacks-on-civilians-spike-in-mali-as-security-deteriorates-across-the-sahel/.

[10] Opalo, Ken. 2024. “Making Lasting Peace in the Sahel,” January 8. https://www.africanistperspective.com/p/making-lasting-peace-in-the-sahel?utm_medium=reader2.

[11] The New Humanitarian. 2022. “’We Accept to Save Our Lives’.”

[12] Dakono, Baba. 2022. From a Focus on Security to Diplomatic Dialogue: Should a Negotiated Stability Be Considered in the Sahel? FES Peace and Security Series, no. 45. Dakar-Fann, Senegal: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Peace and Security.

[13] Opalo, Ken, and Kim Yi Dionne. Accessed June 5, 2024. “Good Authority: Don’t Call It a ‘Coup Epidemic’ in Africa.” Ufahamu Africa. https://www.ufahamuafrica.com/2024/05/04/good-authority-dont-call-it-a-coup-epidemic-in-africa/.

[14] Jeune Afrique. “Mahmoud Dicko: ‘Au Mali, Ce n’est Pas à La France d’imposer Ses Solutions’.” Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1187147/politique/mahmoud-dicko-au-mali-ce-nest-pas-a-la-france-dimposer-ses-solutions/.

[15] Harvard International Review. 2023. “How France Failed Mali: The End of Operation Barkhane,” January 30. https://hir.harvard.edu/how-france-failed-mali-the-end-of-operation-barkhane/.

[16] Dakono. 2022. From a Focus on Security to Diplomatic Dialogue.

[17] Opalo & Dionne. “Good Authority: Don’t Call It a ‘Coup Epidemic’ in Africa.”

[18] Nsaibia. 2023. “Fact Sheet: Attacks on Civilians Spike in Mali as Security Deteriorates Across the Sahel.”

[19] Dakono. 2022. From a Focus on Security to Diplomatic Dialogue.

[20] Conciliation Resources. “Mali’s Peace Process: Context, Analysis and Evaluation.” Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.c-r.org/accord/public-participation/malis-peace-process-context-analysis-and-evaluation.

[21] International Crisis Group. 2024. “Northern Mali: Return to Dialogue,” February 20. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/mali/314-nord-du-mali-revenir-au-dialogue.

[22] Dakono. 2022. From a Focus on Security to Diplomatic Dialogue.

[23] The New Humanitarian. 2022. “’We Accept to Save Our Lives’.”

[24] ReliefWeb. 2020. “Can Dialogue with Violent Extremist Groups Help Bring Stability to Mali?” March 23. https://reliefweb.int/report/mali/can-dialogue-violent-extremist-groups-help-bring-stability-mali.

[25] France 24. 2024. “Mali National Dialogue Recommends Extending Junta Rule for Several More Years,” May 10. https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20240510-mali-national-dialogue-recommends-extending-junta-rule-for-several-more-years.

[26] Dakono. 2022. From a Focus on Security to Diplomatic Dialogue.