By: Indrie Pratiwi

Edited By: Ava LaGressa

The 2024 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29) in Baku, Azerbaijan, finished strong on Sunday, November 24th, 2024, with a significant milestone in global climate finance. With nearly 200 nations in attendance, the conference achieved a breakthrough agreement to triple annual funding for developing countries, increasing it from the previous target of US $100 billion to US $300 billion by 2035.1

The Paris Agreement, signed by nearly 200 countries, sets a collective ambition to limit global warming to below 2°C, ideally 1.5°C, compared to pre-industrial levels. Transitioning to renewable energy is essential to mitigating climate change and offers co-benefits such as improved air quality, energy security, and job creation. However, despite technological advancements and decreasing costs, the global energy mix remains dominated by coal, oil, and gas.2 Emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), which account for the majority of future energy demand growth, must embrace clean energy at scale. This is a daunting task given the structural and financial barriers they face, requiring international cooperation and innovative financing mechanisms.

Emerging markets face numerous barriers to clean energy adoption, many of which are financial. High upfront costs for renewable energy infrastructure deter investment, especially in countries with limited access to affordable financing. While solar and wind technologies are becoming more cost-competitive, many EMDEs lack the financial ecosystem needed to support large-scale projects. Regulatory and political instability further compound the problem. Many investors perceive EMDEs as high-risk environments due to policy inconsistencies, currency volatility, and underdeveloped financial markets.3 Additionally, these countries often lack the technical expertise and infrastructure required to design, implement, and maintain clean energy systems.

Finally, the prioritization of immediate economic development over long-term climate goals poses a challenge. Governments in EMDEs may be reluctant to allocate resources to clean energy projects without clear economic incentives or substantial international support. For example, Indonesia’s commitment to reducing coal usage has encountered obstacles, particularly in securing international funding. The 2022 Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) pledged $20 billion to assist Indonesia’s energy transition. However, as of September 2024, these funds have not been disbursed.4 This has been holding back plans to retire coal-fired power plants like the 660-MW Cirebon-1. Senior Indonesian officials have expressed concerns over the lack of grants and the high costs associated with plant retirements. The delay hampers Indonesia’s efforts to decrease emissions from coal power, especially given its status as a leading coal producer.

Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) are uniquely positioned to bridge the financing and capacity gaps in EMDEs to support clean energy projects and achieve climate goals. The commitments made at COPs align closely with the mandates of MDBs, which are designed to provide financial and technical support to developing countries. By mobilizing resources and reducing investment risks, MDBs can help translate COP29’s climate finance goals into tangible progress. Created by multiple countries to promote economic development and poverty alleviation, each MDB has a specific geographical focus and development mandate.

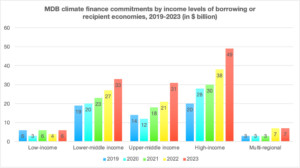

However, despite the geographical significance, all MDBs have been stepping up to become strategic partners for global climate actions. According to the latest annual Joint Report on Multilateral Development Banks’ Climate Finance released in September 2024, MDBs contributed a record-breaking $125 billion in public climate finance in 2023, with 60% ($74.7 billion) allocated to low- and middle-income countries.5 This report is composed by AfDB, ADB, AIIB, CEB, EBRD, EIB, IDBG, IsDB, NDB, and WBG.6

Source: 2023 Joint Report on Multilateral Development Banks’ Climate Finance 7

MDBs’ commitment to addressing climate challenges in emerging and developing economies can be seen based on the above graph. Between 2019 and 2023, MDBs allocated substantial and steadily increasing climate finance to low-, lower-middle-, and upper-middle-income countries, with a rise from approximately $39 billion in 2019 to $70 billion in 2023.8

A major barrier to clean energy investment in EMDEs is the high level of perceived risk. MDBs mitigate these risks through various de-risking mechanisms, such as guarantees, insurance products, and concessional loans. For example, the World Bank’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) offers political risk insurance, protecting investors against risks like expropriation and contract breaches. Similarly, ADB provides credit enhancement tools to attract private investment into renewable energy projects.9 By sharing investment risks, MDBs make clean energy projects in EMDEs more attractive to private investors. The financial viability of clean energy projects in EMDEs is often uncertain due to underdeveloped regulatory frameworks, volatile markets, and weak infrastructure.

MDBs address this challenge by providing concessional financing, which lowers the cost of capital for project developers. Concessional loans, offered at below-market interest rates, help projects achieve financial sustainability. MDBs also facilitate public-private partnerships (PPPs), blending public-sector support with private-sector innovation. The AfDB’s support for the Noor Ouarzazate Solar Complex in Morocco exemplifies how MDBs can drive successful renewable energy projects in EMDEs. Transparency is vital for ensuring the efficient and equitable use of climate finance. MDBs enforce rigorous standards for project appraisal, monitoring, and reporting, reducing the risks of inefficiency and corruption.

Uncertainty is what MDBs have been dealing with. In terms of financing, MDBs often struggle to attract private sector investment for climate projects due to perceived high risks and insufficient risk mitigation strategies. For instance, asset managers have noted that the risks and restrictions imposed by development banks can deter private investment.10 The demand for climate finance far exceeds the current supply. Developing countries have called for over $1 trillion annually by 2030, but recent commitments, such as the $300 billion target set at COP29, fall short of these needs.11

For example, in Indonesia, MDBs have faced challenges in mobilizing private investment for renewable energy projects, primarily due to inconsistent regulatory frameworks and concerns over project bankability, which have disincentivized private sectors to participate.12 Similarly, in Africa, the Inga Dam project in the Democratic Republic of Congo has faced repeated delays due to political instability and inadequate risk-sharing mechanisms, which then discouraged private investors from committing to this large-scale renewable energy initiative.13

Shifts in political leadership can significantly impact MDBs’ long-term strategies and planning. When leaders skeptical of climate change, such as Donald Trump, are elected or re-elected, it can result in reduced political support for global climate initiatives and a rollback of climate-friendly policies. This shift can diminish MDBs’ ability to align their goals with the international climate agenda.14 Moreover, MDBs often operate in a wide array of countries, each with its own unique regulatory framework. In some cases, they are subject to sudden changes due to political volatility. For instance, inconsistent environmental regulations or unexpected policy shifts can lead to project delays, increased costs, or even project cancellations. This heightened level of uncertainty and risk complicates project implementation. Then it is difficult for MDBs to ensure the timely and effective deployment of climate finance.

In dealing with financial uncertainty, MDBs should expand their capitalization through contributions from member countries, allowing them to scale up concessional financing and risk mitigation instruments. Risk-sharing mechanisms, such as guarantees and blended finance, should be further developed to attract private-sector investment and reduce the perceived risks of clean energy projects. For example, MDBs can emulate the World Bank’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), which provides political risk insurance to de-risk investments in high-risk countries. Crowding in private investment has always been one of the most important strategies in supporting climate finance. MDBs should actively engage with private investors by offering co-financing opportunities, green bonds, and structured financial products that align with private-sector risk appetites. Partnerships with institutional investors, such as pension funds and sovereign wealth funds, can unlock large pools of capital for renewable energy projects.

Uncertainty over the availability of long-term funding often discourages private investors from participating in MDB-led projects. MDBs should prioritize multi-decade financial commitments to align with the lifecycle of clean energy infrastructure. A strategy to implement it could be by structuring financing mechanisms, such as sustainability-linked bonds, to provide stable and predictable long-term project funding. MDBs should also advocate for streamlined access to international climate funds, such as those committed at COP29, to ensure timely and transparent disbursements. This includes simplifying application processes and aligning disbursement schedules with project timelines. To do this, MDBs could act as intermediaries between international climate finance providers and recipient governments to facilitate the flow of funds.

Works Cited

1. UNFCCC. 2024. “COP29 UN Climate Conference Agrees to Triple Finance to Developing Countries, Protecting Lives and Livelihoods.” https://unfccc.int/news/cop29-un-climate-conference-agrees-to-triple-finance-to-developing-countries-protecting-lives-and

2. Perkins, R., and H. Edwardes-Evans. 2023. “Fossil Fuels ‘Stubbornly’ Dominating Global Energy Despite a Surge in Renewables: Energy Institute.” https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/062623-fossil-fuels-stubbornly-dominating-global-energy-despite-surge-in-renewables-energy-institute

3. Furness, V., K. Strohecker, and S. Jessop. 2024. “How Development Banks Are Failing to Attract Enough Private Money to the Climate Fight.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/sustainable-finance-reporting/beyond-b-loans-development-banks-seek-private-money-climate-change-fight-2024-11-19/

4. Ibid.

5. Asian Development Bank (ADB), African Development Bank (AfDB), Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), European Investment Bank (EIB), Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), Inter-American Investment Corporation (IDB Invest), Islamic Development Bank (IsDB), New Development Bank (NDB), and World Bank Group. 2024. 2023 Joint Report on Multilateral Development Banks Climate Finance. IDB Publications. https://doi.org/10.18235/0013160

6. AfDB = African Development Bank, ADB = Asian Development Bank, AIIB = Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, CEB = Council of Europe Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the European Investment Bank (EIB), the Inter-American Development Bank Group (IDBG), the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB), the New Development Bank (NDB) and the World Bank Group (WBG).

7. Development Bank (ADB) et al. 2024. 2023 Joint Report on Multilateral Development Banks Climate Finance.

8. Bank Group. 2021. “MIGA Trust Fund to Reduce Political Risk for Renewable Energy Tech Entrepreneurs | World Bank Group Guarantees | MIGA.” https://www.miga.org/press-release/miga-trust-fund-reduce-political-risk-renewable-energy-tech-entrepreneurs

9. Furness, V., K. Strohecker, and S. Jessop. 2024. “How Development Banks Are Failing to Attract Enough Private Money to the Climate Fight.” Reuters.

10. Dalton, M. 2024. “U.N. Reaches $300 Billion Climate Financing Deal as Trump Looms.” Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/world/u-n-reaches-300-billion-climate-financing-deal-as-trump-waits-in-the-wings-656ed18e

11. Climate Policy Initiative. 2022. “Paris Alignment of Power Sector Finance Flows in Indonesia: Challenges, Opportunities and Innovative Solutions.” https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/paris-alignment-of-power-sector-finance-flows-in-indonesia-challenges-opportunities-and-innovative-solutions/

12. International Rivers. 2024. “Inga Campaign.” https://www.internationalrivers.org/where-we-work/africa/congo/inga-campaign/

13. Lederer, E., and J. Keaten. 2024. “The United Nations Faces Uncertainty as Trump Returns to US Presidency.” AP News. https://apnews.com/article/united-nations-trump-wto-health-guterres-tedros-f2cf2b72f0efa4b66d12ce211a78a9e7

14. Ibid.