Image via Wikimedia Commons

Throughout Europe, housing is a human right. One would assume that this would be true for all citizens of the European Union, right? Unfortunately, this is not so for many of the migrant Roma living in France. It was not that long ago that Mihaiela Cirpaciu was forced to leave a Bobingy slum with only her daughter and a shopping cart full of suitcases. She and her daughter are two of the many Roma forced out of their homes in France.

Originally from India, the Roma are an ethnic minority that immigrated to Europe about 1,400 years ago. There are around 10 or 12 million Roma people in Europe, and about 6 million live within and are citizens of the European Union. As European citizens can travel freely across the borders, Roma people in Eastern European countries have begun moving to Western European countries for better healthcare and education opportunities. As a marginalized ethnic group throughout Europe, the Roma, particularly in France, are discriminated against and forced out of society.

According to European Roma Rights Centre, there are nearly 400,000 Roma living in France (including people of related ethnic groups like the Gens du voyage, Manouche, and Kale). This is about 0.64% of the French population. The migrant Roma population in France is rather small, between 15,000 and 20,000. However, these numbers are not exact because France does not legally recognize cultural or ethnic minorities, and ethnically disaggregated data are therefore not available.

Recently, international human rights groups, such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and European Roma Rights Center, have criticized France for its forced evictions of Roma people. Forced eviction—the removal of people from their lands and homes without legal processes, prior information, or their consent—is a human rights violation France is part of several United Nations and European Union treaties (including the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the European Convention on Human Rights) that ban forced evictions, discrimination against all people, and require that the government provide adequate housing for all homeless people. French Housing Law recognizes the right to housing. In addition, a French law from 2007 states that housing is an enforceable right. France has also introduced measures such as the Dalo Act to promote access to housing for everyone who cannot afford it, as well as promote the social inclusion of these people. According to Amnesty International, France’s Social Action and Family Code aims to provide unconditional housing for homeless people everywhere and ensure that they are provided with adequate living standards and social support. However, these provisions are not carried out in reality. Often, living facilities are not appropriate for families or they must wait in long lines for housing options; even worse, sometimes they can only stay in the housing for a few days. For these families, this is not a stable solution. Amnesty International has reported that in the summer of 2013, 76% of requests for shelter were not met, leaving families all around the country homeless. Overall, human rights conditions in France are good. However, racism and xenophobia continue to damage the lives of migrant Roma people, who have lost their rights to housing, clean water, healthcare, and education.

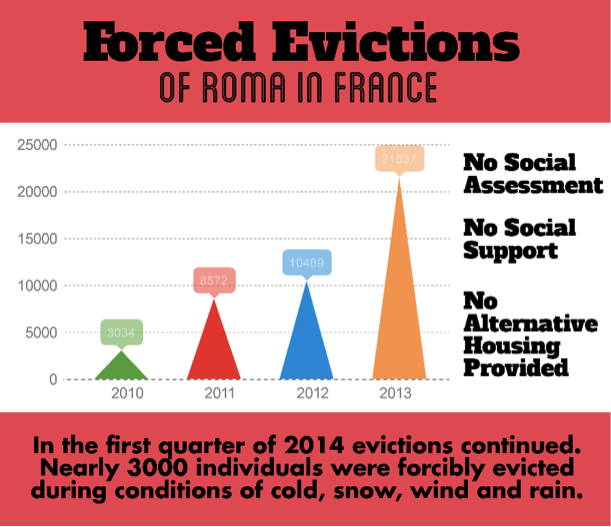

In 2012, French President Hollande was elected, and earlier in 2014 Prime Minister Valls took office. Although France’s new leaders claim that the government is trying to pursue policies to end forced evictions, current statistics show otherwise. According to the European Roma Rights Center, there has been a large increase in the number of people being forcefully evicted, from 3,034 in 2010 to 21,537 in 2013.

Furthermore, in 2013 French Prime Minister Manuel Valls openly expressed anti-immigrant sentiments when he stated that the Roma should leave France: “The Roma should return to their country and be integrated over there…They should return to Romania or Bulgaria and for that the European Union, with the Bulgarian and Romanian authorities must ensure these populations are firstly integrated in their countries.” He went on to say that the full integration of the Roma into French society was not possible, stating, “There is no other solution than dismantling these camps progressively and deporting (the Roma).” It seems that Prime Minister Manuel Valls has forgotten that many of the Roma are citizens of both France and the European Union. He continues to paint them as outsiders who do not fit into French society. When the French government’s leaders are openly discriminating against them, in addition to violating domestic and international housing laws, one can imagine the intense levels of discrimination the Roma people face from other citizens.

While few international governments have expressed reactions to France’s actions, many NGOs have been concerned with the situation, including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and European Roma Rights Centre. This past May, the European Court of Human Rights started to question France’s eviction policies with the ‘Hirtu and Others v. France’ case. In April, the Court gave a notice of application to the French government and noted the articles related to this case. They stated that France could possibly be in violation of Article 3 (the prohibition of torture and inhuman or degrading treatment), Article 8 (the right to respect for private and family life), and Article 13 (right to an effective remedy) of the European Human Rights Convention. This case is particularly important because the European Court of Human Rights’ decisions are binding for governments. It is clear that forced evictions are hurting many Roma lives and causing homelessness and poverty. The steps that are now being taken are crucial for the protection of human rights. As the United Nations Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights explains, “Evictions must be carried out lawfully, only in exceptional circumstances, and in full accordance with relevant provisions of international human rights and humanitarian law.” That is not what is happening in France. The countries of the European Union must be more active and hold France accountable for these evictions. Both international and French domestic law prohibit forced evictions. Why don’t they?