Source: Alex Popov

Written by: James Warren

Edited by: Adam Terragnoli

Background:

In the early half of the twentieth century, smog clouded the air over Los Angeles and other major metropolitan areas. It became evident that this smog was emanating from the dense traffic of the city in addition to stationary industrial sources.[1] In order to respond to public health concerns about the pollution caused by motor vehicles, the Clean Air Act was signed into law in 1963.[2] Rudimentary at first, the act was amended over several years to allow the federal government to regulate air pollution from industrial and transportation sources alike.[3] Since the passage of the Clean Air Act, limiting pollutants emitted by cars has been a regular practice of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA).[4]

Regulatory Shift:

In an unprecedented and controversial decision, the Trump administration announced on September 18, 2019, that it would roll back emission standards set by the CAFE (Corporate Average Fuel Economy) and rescind California’s waiver to the Clean Air Act, which allowed the state to set its own emission standards.[5] The CAFE standards, set by the Obama administration in 2012, required car manufacturers to maintain an average fleet efficiency, or a fuel efficiency measured across all cars sold in the United States, which would increase over the next seven years.[6] The reevaluation instigated by the Trump administration cited safety concerns over individuals potentially not purchasing newer, safer vehicles due to inflated cost, overly stringent restrictions on the auto industry, and worries about slowed growth of the US automotive market.[7] As a result of the concerns cited in the reevaluation, the Trump administration created a new regulatory rule, SAFE (Safer Affordable Fuel-Economy), which goes into effect November 26, 2019.[8]

California’s self-imposed regulation, courtesy of the Clean Air Act waiver, is in line with the previous administration’s federal requirements. California and the 13 states that follow its guidelines typically would be unaffected by this rollback, but the removal of California’s waiver has crippled their longstanding ability to self-regulate. In response to this decision, 23 US states have filed suit to allow California to keep its waiver.[9] The pending result of that lawsuit introduces uncertainty into the auto industry, which may have to deal with two standards – the lower federal standard and the higher Californian standard.[10] 17 automotive companies including American automakers Ford and GM, as well as the United Automobile Workers (UAW), a powerful auto workers union, petitioned the government to reconsider the choice to lower standards.[11] This begs the question, if economic models predict that deregulation leads to lower private costs, why would automakers and auto workers alike protest the action to deregulate their industry?

The Regulatory Landscape:

In a regulatory environment marked by increasing fuel efficiency standards since the 1960s, corporate actors have had to incorporate these standards into company decision-making. As new automobiles take three to five years to develop, companies have already invested in factories and infrastructure capable of supplying higher-efficiency vehicles.[12] Further, with clear guidelines for increased efficiency over the next five years, car companies are incentivized to develop autos which exceed fuel efficiency guidelines. Without these regulatory incentives, companies are less motivated to finance long-term efficiency investments. This is because economy car manufacturers can undercut competitors by underinvesting in expensive, state-of-the-art equipment and technology. In this case, it is not goodwill which prompts the corporation toward sustainability and innovation, but profits coincident with an expectation of US industry regulation.

The rollback further endangers an innovative auto industry, as it increases the risk of companies avoiding long-term R&D. In a June letter regarding the proposed regulatory rollback, industry executives stated,

For our companies, a broadly supported final rule would provide regulatory certainty and enhance our ability to invest and innovate by avoiding an extended period of litigation and instability, which could prove as untenable as the current program.[13]

A company which cannot reliably predict how it will be regulated in three years is undertaking a risk with any long-term investment. Government predictability through uniform executive standards allows companies to innovate in products which benefit the company, consumer, and environment with low risk. Governments around the world have been pushing for high-efficiency, low-emission vehicles.[14] In light of this push, UAW President, Dennis Williams, stated, “it would be counterproductive to enact policies that provide disincentives for investing in advanced technologies and improving efficiency.”[15] It is uncommon to see business and labor united around an issue, and this joinder speaks to the importance of a stable regulatory environment.

In Defense of the Rollback:

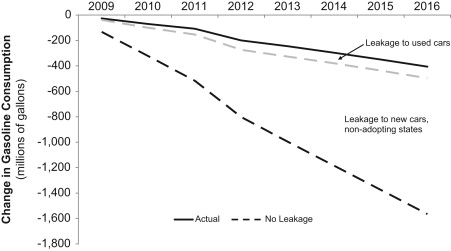

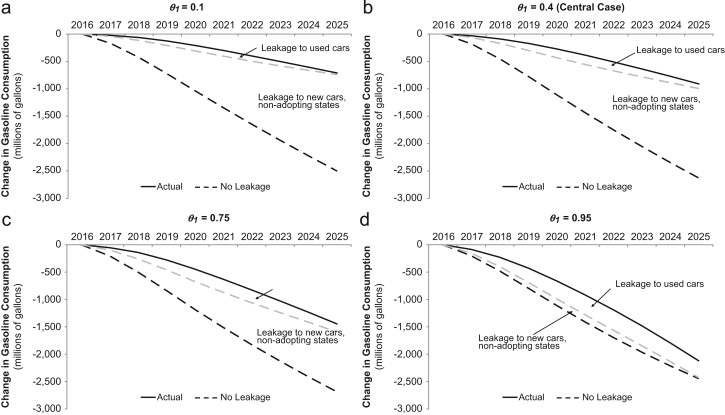

Defenders of the rollback emphasize that lower-efficiency vehicles sold in states without California’s standards offset the reduced emissions from higher-efficiency vehicles.[16] While the technological innovations used for high-efficiency vehicles will eventually affect the rest of the market, conservative estimates suggest the overall emission reduction will be inconsequential (fig. 1).[17] These critiques do not consider California as a historical leader for setting the United States’ climate policy agenda. Because California policy often precedes and predicts US policy, the California waiver provides more regulatory and market certainty instead of less.[18] Further, less conservative calculations of the effect of technological dissemination show a more profound effect on total reduction of emissions across the fleet (fig. 2).[19]

Conclusion:

While not altruistically motivated, the auto industry benefits society when it invests in efficiency technologies that outpace tightening regulations. For investment to occur, automakers must be confident in the stability of the landscape of risks which lie before any choice they might make. High among these risks is US regulation. By reneging on its previous regulatory commitments, the United States disrupts the market, imperiling faith in its ability to provide a stable atmosphere for economic growth. In doing so, it disincentivizes sustainability and efficiency innovation and research, and drives companies to production and investment outside the United States.[20]

This disincentivizing effect is not specific to the automotive industry, but is a portent of how markets will respond to risk changes due to regulation in any market, as seen in telecommunications, the airline industry, and electricity generation.[21] Regulatory predictability not only increases long-term investment, and thus profits, for firms, but incentivizes those firms to reduce emissions, produce durable technology, and keep jobs domestic.[22]

Figures:

Figure 1: Conservative estimates show that technological advancements have little effect on emissions reductions

Figure 2: Varied estimates of greater technological integration into economy car production show a profound effect on emissions reduction

References

- “History,” (California Air Resources Board), accessed September 30, 2019, https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/about/history. ↑

- Emission standards for new motor vehicles or new motor vehicle engines. U.S. Code 42 (2013), §7521. ↑

- “Evolution of the Clean Air Act,” EPA (Environmental Protection Agency, January 3, 2017), https://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview/evolution-clean-air-act. ↑

- “Timeline of Major Accomplishments in Transportation, Air Pollution, and Climate Change,” EPA (Environmental Protection Agency, January 10, 2017), https://www.epa.gov/transportation-air-pollution-and-climate-change/timeline-major-accomplishments-transportation-air. ↑

- Coral Davenport, “Trump to Revoke California’s Authority to Set Stricter Auto Emissions Rules,” The New York Times (The New York Times, September 17, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/17/climate/trump-california-emissions-waiver.html. ↑

- Environmental Protection Agency and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Notice of proposed rulemaking. “The Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule for Model Years 2021–2026 Passenger Cars and Light Trucks,” Federal Register 83, no. 165 (August 24, 2018): 42986-43000, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-08-24/pdf/2018-16820.pdf. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Environmental Protection Agency and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Final Rule. “The Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule,” Federal Register 84, no. 188 (September 27, 2019): 51310, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-09-27/pdf/2019-20672.pdf. ↑

- David Shepardson, “California, Other States Take Trump to Court over Auto Emissions Rules,” Reuters (Thomson Reuters, September 20, 2019), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-autos-emissions-lawsuit/california-other-states-sue-trump-administration-over-auto-emissions-rules-idUSKBN1W51ZU. ↑

- Coral Davenport, “Automakers Tell Trump His Pollution Rules Could Mean ‘Untenable’ Instability and Lower Profits,” The New York Times (The New York Times, June 6, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/06/climate/trump-auto-emissions-rollback-letter.html?module=inline. ↑

- Aston Martin Lagonda, Ltd., BMW North America, Ford Motor Company, General Motors Company, Honda North America, Inc., Hyundai Motor America, Jaguar Land Rover North America, LLC, Kia Motors America, Mazda North American Operations, Mercedes-Benz USA, LLC, Mitsubishi Motors North America, Inc.. Nissan North America, Inc., Porsche Cars North America, Inc., Subaru of America, Inc., Toyota Motor North America, Inc., Volkswagen Group of America, and Volvo Car Corporation to President Donald Trump, June 6, 2019, Detroit Free Press, http://media.freep.com/uploads/digital/Trump-GHG-CAFE-Letter-June-6-2019.pdf ↑

- Umair Irfan, “Trump’s EPA Is Fighting California over a Fuel Economy Rule the Auto Industry Doesn’t Even Want,” Vox (Vox, April 6, 2019), https://www.vox.com/2019/4/6/18295544/epa-california-fuel-economy-mpg. ↑

- Aston Martin Lagonda, Ltd. et al. to President Donald Trump, June 6, 2019, Detroit Free Press. ↑

- Shikha Rokadiya and Zifei Yang, “Overview of Global Zero-Emission Vehicle Mandate Programs,” The International Council on Clean Transportation, April 24, 2019, https://theicct.org/publications/global-zero-emission-vehicle-mandate-program. ↑

- Dennis Williams, “Determinations: Appropriateness of the Model Year 2022-2025 Light-Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emissions Standards under the Midterm Evaluation Docket ID No. EPA-HQ-OAR-2015-0827 Comments Submitted by President Dennis Williams, International Union, UAW,” Dennis Williams to Gina McCarthy, December 30, 2016, in Environmental Defense Fund. Accessed September 22, 2019. http://blogs.edf.org/climate411/files/2017/03/UAW-proposed-determination.pdf. ↑

- James Sallee, “Waving Goodbye to the California Waiver?,” Energy Institute Blog, September 23, 2019, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2019/09/23/waving-goodbye-to-the-california-waiver/. ↑

- Lawrence H. Goulder, Mark R. Jacobsen, and Arthur A. Van Benthem, “Unintended Consequences from Nested State and Federal Regulations: The Case of the Pavley Greenhouse-Gas-per-Mile Limits,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 63, no. 2 (2012): 187-207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2011.07.003. ↑

- David Vogel, California Greenin: How the Golden State Became an Environmental Leader (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019): 189-230. ↑

- Lawrence H. Goulder, “Unintended Consequences…” 187-207. ↑

- Luke A. Stewart “The Impact of Regulation on Innovation in the United States: A Cross-Industry Literature Review.” (June 2011): 3-4. ↑

- Paul A. Grout and Anna Zalewska, “The Impact of Regulation on Market Risk,” Journal of Financial Economics 80, no. 1 (April 2006): pp. 153-154. ↑

- John Irons and Isaac Shapiro, “Regulation, Employment, and the Economy: Fears of Job Loss Are Overblown,” Economic Policy Institute, April 12, 2011, https://www.epi.org/publication/regulation_employment_and_the_economy_fears_of_job_loss_are_overblown/. ↑