Source: Etienne Martin

Written by Giovanni J.A. Ugut

Edited by Ernest Lemayian

On April 22, 2016, in Paris, France, 195 countries signed the Paris Agreement. The agreement laid out the necessary frameworks and goals regarding greenhouse-gas emissions mitigation, finance, and adaptation with the goal of limiting the increase in global temperatures to well below two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.1. To satisfy these ambitious goals, the European Union (EU) enacted a 20/20/20 approach: a 20% reduction of CO2 emissions, a 20% increase in energy efficiency, and an increase to 20% of market share for renewables. 2

Such an approach has profound implications on tomorrow’s economic structure. Against the backdrop of increasing energy needs and continuously increasing economic growth, the International Energy Agency has forecasted that electricity sales will grow to ~35% of total energy demand by 2040. 3 Furthermore, renewables are expected to take around ~67% of global energy generation.4

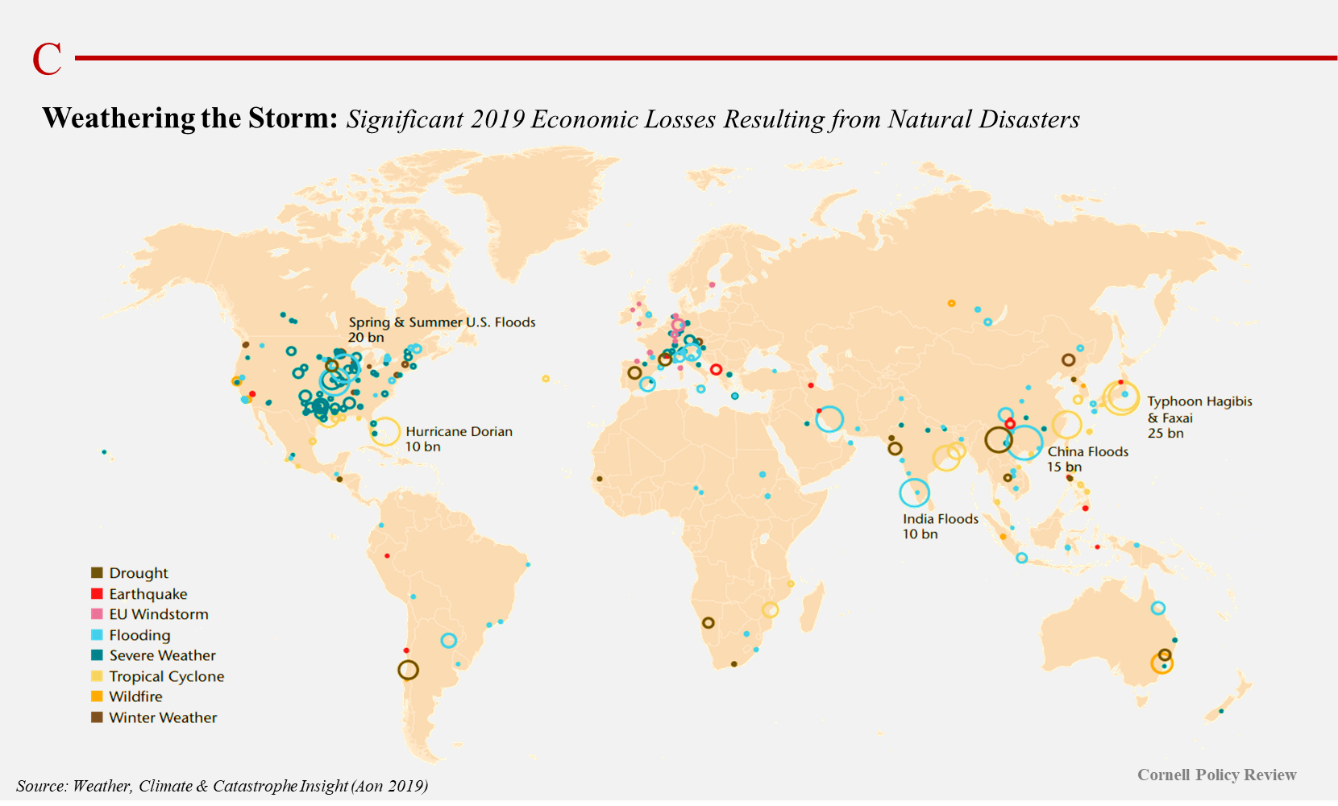

Achieving this kind of global economy-wide structural transformation requires large amounts of investments across different sectors. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development projects an estimated $6.9tn per year until 2030 of infrastructure investment to meet development needs and make it compatible with the Paris Agreement.5 Meanwhile, a joint report by the Paulson Institute and the Cornell Atkinson Center states that between $594bn and $824bn is needed to close the biodiversity gap.6 However, the financial effects of environmental risks are not only limited to the needed economic transformation. The economy must handle possible environmental risks triggering insurance events that could leave insurers on the hook. AON, an Anglo-Irish-American insurance company, stated that in 2019 extreme climate events created an economic loss of around $232bn. There is much room to grow in this space as the global insurance gap for natural disasters is around $161bn.7 Swiss Reinsurance Company found that only around 35% of catastrophe risks are covered in developed countries – this figure is 6% for developing countries.8

When juxtaposed against chronic underfunding in a climate of prevailing low interest rates and the expectation of a growing list of natural disasters, these figures highlight the increasingly important role the financial sector and its prime mover – the central bank – will continue to play in supporting the transition to a low-carbon economic paradigm.

A Green Perspective on Central Banks’ Traditional Responsibilities

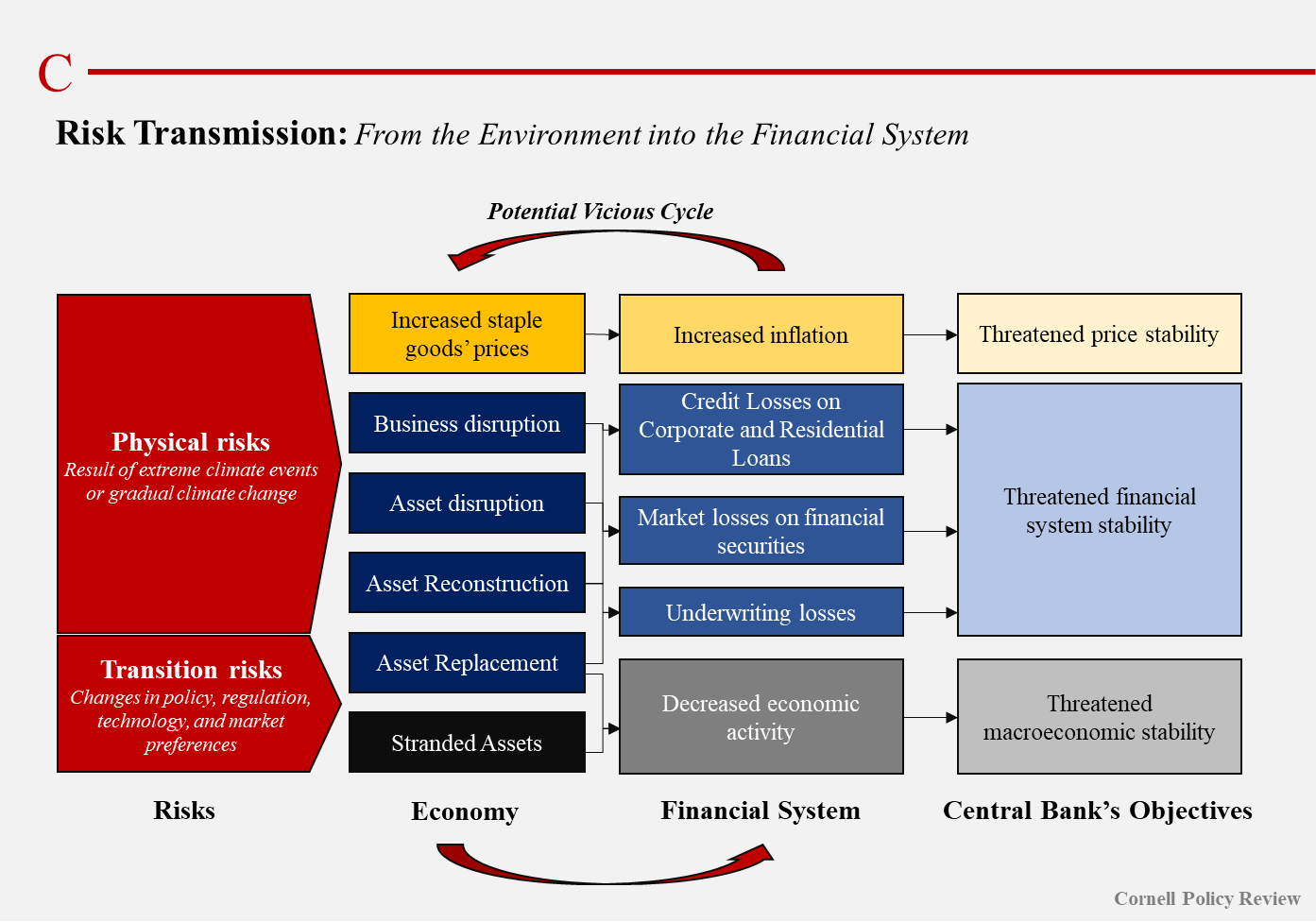

Modern central banks have two primary mandates: safeguarding price stability, represented by low and stable inflation, and maintaining financial system stability. A secondary mandate is the support of broader macroeconomic goals such as sustainable growth or full employment.9 These policy goals are becoming increasingly impacted by environmental and climate change risks.

Consider the case of an agricultural-based economy. Physical risks, such as droughts and floods, can directly impact agricultural production and related adjacencies. In addition to food insecurity, this may create price instability – especially as most developing countries’ consumer price index basket of goods are heavily weighted with food and agricultural output.10

Additionally, transitioning to a low-carbon economic paradigm may create price instability.11 Currently, there are approximately 40 governments worldwide that have sought to price carbon either through taxation or cap-and-trade mechanisms.12 These policies may result in potentially reduced output and an inflationary increase. A 2017 modeling exercise by Goulder and Hafstead estimated that a $40 per ton carbon tax, coupled with a 5% per annum increase, would reduce GDP by just over 1% in 2035.13 This leaves the central bank pulled between two directions. When considering its secondary goal of economic growth, a central bank would respond to this situation by decreasing interest rates, which may cause further inflation. Concerning its primary goal of strictly safeguarding price stability, the central bank will increase its interest rate further slowing down the economy, which in many regards may be a worse policy outcome than the intended price stability.

Financial stability, characterized by the financial system’s ability to allocate funds, withstand, and absorb shocks, and prevent adverse effects from impacting the real economy, is adversely impacted by climate change through two vectors: physical and transitional risks.14 Physical risks, which may leave assets damaged or impaired, can adversely impact the insurance industry with increased claims and the banking sector through increased credit delinquency resulting from a sharp decrease in asset productivity. 15 Transitional risks, which are most likely to arise from governmental/regulatory policy, may leave assets stranded, impacting carbon-heavy assets’ and companies’ valuations, and can potentially trigger systemic risk events.15 In either case, these risks arise because of market failure as the economy fails to properly account for critical environmental events that are usually out of the scope of many accounting and risk management frameworks, thereby leading to private returns that are not necessarily aligned with true economic returns.

As such, central banks face an imperative to factor in these risks into their policy toolkit.

Central Banks’ Green Policy Toolkit

Assuming that central banks have the necessary requisite legal mandates to pursue sustainability and environmental policy objectives, prudential regulations and traditional monetary policies can help achieve said targets.

Central banks and financial authorities can mandate banks under their auspices to adopt stringent environmental and sustainability risk management standards and enact uniform disclosure practices – allowing the financial services industry to internalize its exposure to environmental risks. Furthermore, central banks can transpose existing monetary policies to a new green paradigm. This will safeguard financial stability by being ahead of the curve on systemic environmental risk.

To effectively manage banking risks, most banks and regulatory authorities refer to and implement, either fully or on a piece-meal basis, the Basel III framework – a mostly voluntary regulatory framework on bank capital adequacy, stress testing, and liquidity risk. However, the overarching Basel framework is narrowly focused on transactions and assessing the impact of environmental events on a bank’s credit and operational exposures – i.e., a creditors’ ability to meet certain financial obligations, as opposed to broader systemic risks. Much of this exclusion results from a gap between stakeholders’ recognizing the materiality of environmental risks and proactively incorporating said risks into long-term strategy – as demonstrated by the European Central Bank and European Banking Authority.16, 17 To this end, central banks, financial regulators, and banks can supplement the Supervisory Review Pillar in Basel III by devising initiatives such as exclusion lists, phase-out/in schedules for certain types of (un)sustainable activities, impact screening, and use of forward-looking models to better understand the banking sector’s environmental risk exposure.

Once these environmental risks have been assessed, they should be properly disclosed to capital market participants, empowering them to be more cognizant of the bank’s exposure to these risks and develop a better sense of risk-adjusted profitability levels. 16 The current Basel framework does not explicitly mandate the disclosure of environmental systemic risks. To mitigate this, central banks and regulatory authorities can create a harmonized and standardized statistical disclosure framework – existing industry classification systems such as the International Standard Industrial Classification allow for uniform classification and interpretation of economic activities.18 Listed French companies and financial institutions are mandated to disclose environmental and social risk exposures vis-à-vis the company’s business model, performance, and soundness. 19

Traditional monetary policies can be further applied to foster investment in green and sustainable projects. Required reserves, which are the amounts that must be held at the central bank by commercial banks, can be used to incentivize the financing and promotion of green assets or to discourage funding brown assets. This can be achieved by setting different reserve rates across portfolios of different asset-types: green sustainable assets or brown carbon-intensive. The Banque du Liban, Lebanon’s central bank, supports green credit by lowering the reserve requirements for green projects by an amount of 100-150% of the loan value if the bank’s customer can provide a certificate demonstrating the project’s potential energy savings.20

In a similar vein to differential required reserves, central banks can mandate commercial banks to have differentiated capital requirements, the amount of liquid assets banks keep on hand to ensure that loans are properly capitalized. Referring back to the Basel III framework, longer-term project finance loans have a higher risk weighting than shorter-term corporate loans; the former tends to be riskier due to the non-recourse nature of the loans. 21 When applying differentiated capital requirements, policymakers must note what is the most common form of green financing that prevails in their country; often, it is not as simply defined along the lines of loan maturity. Most of the green financing in Brazil and China occurs through short-term corporate lending, whereas countries like Peru and South Africa mostly implement longer-term project finance loans.16 Another concern of taking this approach is that it may pit sustainable environmental development against financial system stability – especially if banks are incentivized to shift towards riskier loans.

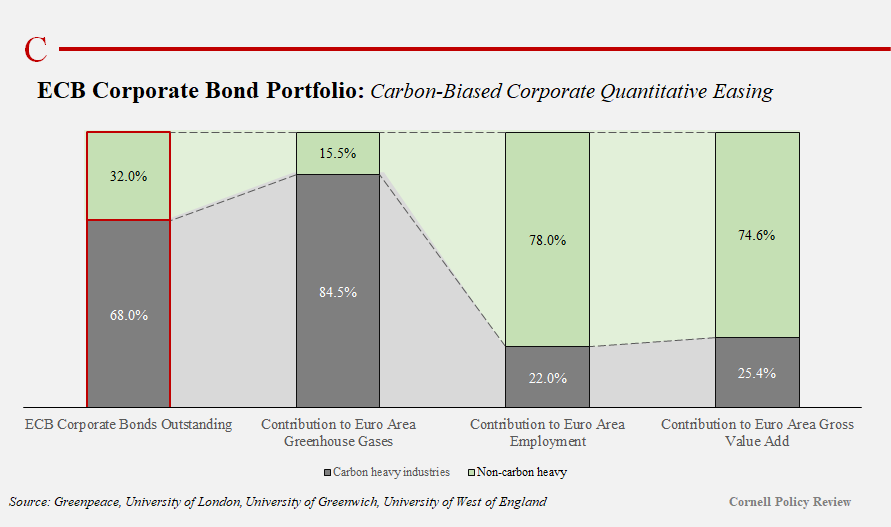

Finally, large-scale asset purchases, also known as quantitative easing, can help achieve certain environmental goals. Central banks would need to place conditions on their purchases which will ultimately promote investment in environmental development. Social impact investment frameworks such as the UN Principles on Responsible Investing can serve as a useful guide. Christine Lagarde, the European Central Bank (ECB) President, in a recent speech, said that the ECB is considering environmental factors in its corporate bond purchases, a program that started in 2016 in a bid to address the market failure of under-pricing environmental risks by financial market participants. 22 If the ECB were to carry this out, it would not mirror the composition of the bond market in its purchases. This would be a departure from the market neutrality principle in central banking. This principle, according to environmentalists’ claims, has favored carbon-heavy companies.

A departure from market neutrality in bond purchases may better account for real economic value generation and missed environmental risks. Research by several English universities and Greenpeace found that carbon-heavy industries make up approximately 68% of ECB-held corporate bonds, 84.5% of Euro area greenhouse gases, but only 30% of EU Gross Value Add.23

Concluding thoughts

Central banks have become increasingly more cognizant of environmental risks. Key decision-makers and regulators have deployed familiar tools to factor in environmental factors in the financial system and promote investment in green, sustainable, and climate-resilient technology and business models. However, while prudential policies, such as disclosure and stress tests, make financial institutions more aware of their risk exposure, central banks’ leveraging traditional monetary policy tools to address green issues raise concerns of central bank independence. Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England, once said, “Once climate change becomes a clear and present danger to financial stability, it may already be too late.”24 With governmental policies potentially too slow to react in the face of increasing urgency of climate change, central banks may find a role.

Works Cited

- “Over 150 Countries to Sign the Paris Agreement on Friday 22 April 2016.” United Nations Climate Change, April 18, 2016. https://unfccc.int/news/over-150-countries-to-sign-the-paris-agreement-on-friday-22-april-2016.

- “EU and Climate Change.” Airclim. Accessed January 1, 2021. https://www.airclim.org/eu-and-climate-change.

- “ExxonMobil: Energy and Carbon Summary.” ExxonMobil. Accessed January 2, 2021. https://corporate.exxonmobil.com/-/media/Global/Files/energy-and-carbon-summary/Energy-and-carbon-summary.pdf.

- IEA. “Shares of Global Electricity Generation by Source, 2000-2040.” IEA. Accessed January 2, 2021. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/shares-of-global-electricity-generation-by-source-2000-2040.

- “Financing Climate Futures: Rethinking Infrastructure.” OECD, UN Environment, World Bank. Accessed January 3, 2021. https://www.oecd.org/environment/cc/climate-futures/policy-highlights-financing-climate-futures.pdf.

- “Financing Nature: Closing the Global Biodiversity Financing Gap.” Paulson Institute, September 21, 2020. https://www.paulsoninstitute.org/press_release/financing-nature-closing-the-global-biodiversity-financing-gap/.

- “Weather, Climate & Catastrophe Insight.” AON, January 2020. http://thoughtleadership.aon.com/Documents/20200122-if-natcat2020.pdf?utm_source=ceros&utm_medium=storypage&utm_campaign=natcat20.

- “Sovereign Parametric Catastrophe Bonds As Means To Address The Protection Gap In Emerging Countries.” SeekingAlpha. Kirill Savrassov, June 17, 2020. https://seekingalpha.com/article/4354295-sovereign-parametric-catastrophe-bonds-means-to-address-protection-gap-in-emerging-countries.

- “Monetary Policy and Central Banking.” IMF, March 28, 2019. https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2016/08/01/16/20/Monetary-Policy-and-Central-Banking.

- Yörükoğlu, Mehmet. “Difficulties in Inflation Measurement and Monetary Policy in Emerging Market Economies .” Bank for International Settlements. Accessed January 4, 2021. https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap49v.pdf.

- Cuervo, Javier, and Ved Gandhi. “Carbon Taxes: Their Macroeconomic Effects and Prospects for Global Adoption – A Survey of the Literature.” International Monetary Fund, May 1998. imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/wp9873.pdf.

- Plumer, Brad, and Nadja Popovich. “These Countries Have Prices on Carbon. Are They Working?” The New York Times. The New York Times, April 2, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/04/02/climate/pricing-carbon-emissions.html.

- Metcalf, Gilbert. “The Macroeconomic Impact of Europe’s Carbon Taxes.” National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2020. https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/files/Metcalf_Stock_Macro-Impact-of-EU-Carbon-Taxes_w27488_July-2020.pdf.

- “Financial Stability.” World Bank. Accessed January 18, 2021. https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/gfdr/gfdr-2016/background/financial-stability.

- “Climate Change: What Are the Risks to Financial Stability?” Bank of England, June 14, 2019. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/knowledgebank/climate-change-what-are-the-risks-to-financial-stability.

- “Stability and Sustainability Basel III Final Report.” Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership. University of Cambridge, October 23, 2014. https://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/resources/publication-pdfs/stability-and-sustainability-basel-iii-final-repor.pdf/view.

- “Guide on Climate-Related and Environmental Risks.” European Central Bank, November 2020. https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/ecb/pub/pdf/ssm.202011finalguideonclimate-relatedandenvironmentalrisks~58213f6564.en.pdf?1f98c498cb869019ab89194a118b9db4.

- Nieto, Maria J. “Banks and Environmental Sustainability: Some Reflections from the Perspective of Financial Stability .” CEPS, May 1, 2017. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Maria_Nieto2/publication/317357991_Banks_and_Environmental_Sustainability_Some_reflections_from_the_perspective_of_financial_stability/links/59366a01a6fdcc89e70f3416/Banks-and-Environmental-Sustainability-Some-reflections-from-the-perspective-of-financial-stability.pdf.

- “The French Legislation on Extra-Financial Reporting : Built on Consensus.” Ministère des Affaires Etrangères – France. Office of the Ambassador at large for Corporate Social Responsibility, December 2012. https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Mandatory_reporting_built_on_consensus_in_France.pdf.

- “On the Role of Central Banks in Enhancing Green Finance.” UN Environment, February 2017. https://unepinquiry.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/On_the_Role_of_Central_Banks_in_Enhancing_Green_Finance.pdf.

- “Creating Capacity – Project Finance Lenders Search for a New Paradigm in Changing Regulatory Times.” Mayer Brown, May 9, 2017. https://www.mayerbrown.com/-/media/files/perspectives-events/publications/2017/05/creating-capacity–project-finance-lenders-search/files/update_project-finance-lenders_may17/fileattachment/update_project-finance-lenders_may17.pdf.

- “ECB to Review Make up of Bond Buys in Green Push, Lagarde Says.” Reuters. Thomson Reuters, October 14, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-ecb-policy-climatechange/ecb-to-review-make-up-of-bond-buys-in-green-push-lagarde-says-idUKKBN26Z11K.

- Dafermos, Yannis, Daniela Gabor, Maria Nikolaidi, Adam Pawloff, and Frank van Lerven. “Decarbonising Is Easy: Beyond Market Neutrality in the ECB’s Corporate QE.” New Economics Foundation/Greenpeace, October 2020. https://greenpeace.at/assets/uploads/publications/GreenpeaceNEFReportECB.pdf.

- Carney, Mark. “A New Horizon.” Bank of England, March 21, 2019. https://www.bis.org/review/r190322a.pdf.