Photo credit: (Andrew Burton/Getty Images). Emma Sulkowicz carries a mattress on Columbia University campus in New York City, Sept. 5.

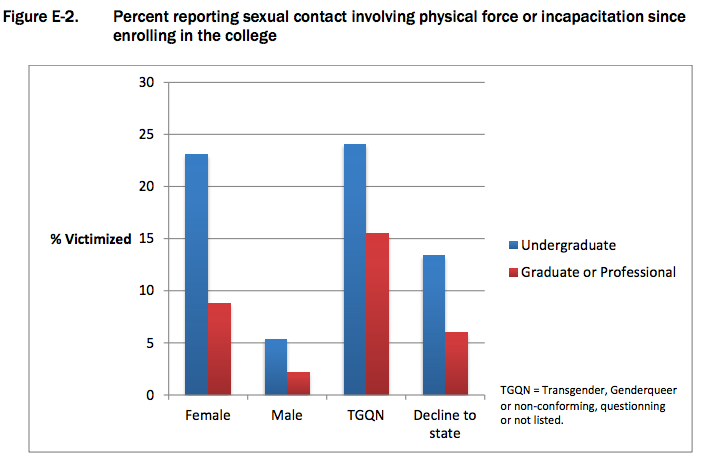

Within the last few years, conversations about a long surviving issue have resurfaced, managing to draw the much –needed attention of higher education institutions across the United States. A stream of alleged cases of Title IX violations, several of which have led to investigations at some of the most prestigious universities across the country, has opened up a dialogue between students and the administrations about sexual violence on college campuses. A recent campus climate survey on sexual assault and sexual misconduct, conducted by the Association of American Universities (AAU), reflects students’ growing concern regarding the issue of sexual violence on campus and the administration’s ability to address its occurrence. The results of the survey affirm the tragic reality that roughly one in five undergraduate women experiences sexual assault on college campuses within her first year. While these chilling statistics depend on gender, class year, and education level (graduate versus undergraduate students), and the numbers vary somewhat from one university to another, even a small number of sexual violence crimes should be deemed unacceptable. In the words of the late Cornell University president, Elizabeth Garrett, “even one instance of sexual assault on our campus is one too many.” Examining Cornell’s sexual assault reporting policies elucidates where the university is succeeding in its efforts, and where it can improve.

Amidst the growing list of prestigious institutions coming under scrutiny for mishandling sexual violence cases, Cornell has begun to take proactive measures to mitigate this issue. As of April 2015, sexual assault and harassment policies have been moved from the Campus Code of Conduct to University Policy 6.4, which outlines how the faculty, staff, and student cases are to be handled . This change includes a switch from a clear and convincing standard to a preponderance of evidence or “more likely than not” based burden of proof, which is a step towards molding the investigation process to be more survivor-centric. While these measures may appear bona fide, the question remains: just how many students are coming forward to report a crime of sexual violence?

Dr. Elizabeth Karns, a senior lecturer of social statistics at the ILR School at Cornell, conducted a comparative study of reporting rates of sexual assault crimes; her study concluded that Cornell University is the worst-performing Ivy League university of similar institutional size. This 2013 study looked at the reporting rates of 1,230 colleges and universities in the United States. Dr. Karns analyzed the Clery data, which shows the total number of crimes reported on campus, which all universities receiving federal funding are mandated to share. From the information she gathered from the Clery data on sexual assaults, she constructed two measures of comparing reporting rates: Assault Report Ratio (ARR) and Reporting Rate per 10,000 (R10K). She defines AAR as the ratio (expressed as a percentage) of reported cases to expected number of cases, and she defines R10K as the number of reported cases divided by student population and expressed as a number per 10,000 students. The expected number of cases of sexual assaults is generated by accounting for the gender ratio of each institution and national statistics on frequency of sexual assault. The average ARR was found to be 2.54%, which means that, on average, only 2.54% of expected cases of sexual assault were actually reported in 2013. The ARR for Cornell University was found to be 1.81%, while rates for other Ivy League universities of similar size—University of Pennsylvania, Columbia University, and Harvard University—were calculated by Karns to be 2.32%, 2.68%, and 4.38% respectively. The data for R10K also placed Cornell at the lowest rank among other Ivy League universities of similar size. These are frightfully low numbers for institutions that pride themselves to be elite establishments, setting standards for other universities to follow.

An important characteristic of this study was the integration of the “expected” number of cases in calculating the ARR that helps us understand the extent of underreporting of this crime on college campuses. A key finding of this report was that just shy of a third of the universities and colleges in the study reported zero sexual assaults in the year 2013. The ubiquity of sexual violence in society, and indeed in these universities, is belied by these figures. The work of Dr. Karns and others encourages exploring the various factors contributing to the rampant underreporting of sexual assaults.

While Clery data provides information about reported incidents of sexual violence, the data is not completely representative of the prevalence of sexual assaults. When compared to the anonymously taken campus climate survey conducted by the AAU in 2014, many discrepancies emerge. The clear gap between the number of people who reported being sexually assaulted on the survey and the number collected through the Clery data arises from a combination of the absence of institutional support to facilitate reporting, the unwillingness of survivors to report the crimes, and the very structure of the Clery data. Clery data shows the number of reported incidents that took place on campus or in nearby areas, excluding any incidents occurring off campus (where a substantial student population may reside). Ugly news of well-known universities manipulating assault cases, and in many instances not considering sexual assault a crime (due to different definitional interpretations of sexual assault), has exacerbated the deep sense of disappointment among concerned students. Further, universities’ licensed counselors, who are meant to be confidential advocates for survivors reporting assaults, have used concerns about confidentiality to justify failing to report numerous incidents. Moreover, the students have only one year from the alleged incident within which they can file an internal formal complaint against another student at Cornell University. This takes away a survivor’s autonomy to take necessary decisions when they feel prepared and instead coerces them to either make a decision within the given span of time or not be able to demand justice from their educational institution.

The AAU survey reflects another aspect of rape culture: a majority of individuals who had been sexually assaulted declined to report these crimes because they thought the crimes were not serious enough. In most cases of sexual assault, the perpetrator is an acquaintance of the survivor and the fear of dangerous repercussions often discourages survivors from filing official complaints. In line with society’s perception, many survivors participate in self-blaming, and feel embarrassed to come forward due to the fear of being outed as a “victim” and disbelieved. Moreover, many students simply lack faith in the authorities’ willingness to provide assistance, as 57.5 percent of female and 38.6 percent of TQGN-identifying graduate/professional students in the AAU report expressed the concern that the officials would not take their report seriously. That these populations, at high risk of assault, profess this perception of the university and law enforcement authorities exposes the frailty of the American higher education system’s accountability towards the students in ensuring safety and justice.

In order to improve the reporting rates at Cornell University, each area of weakness suggested by the AAU survey and other studies needs to be reevaluated and singularly targeted for a more efficient reporting system. Crafting a survivor-centered reporting policy that empowers survivors to share the information about the crime, if they choose to, should be the patent first step. Presently, University Policy 6.4 requires student employees, like RAs, who are potentially the first personnel to be contacted by a survivor of sexual assault, to disclose their status as a non-confidential resource at the moment a survivor chooses to share their story due to the obligation the RAs have to consult with Title IX coordinators. This risks rupturing the trust that the survivor places in this person in that critical moment and can cause them to discontinue the reporting process. Disseminating information about the reporting procedure—including identification of confidential resources, on and off campus—to all students throughout the academic year can instill confidence in survivors to report to the resource of their choice.

Confidentiality is an important element in the complex cases of sexual assault, but providing better education to all students about available resources can potentially improve the trust between survivors and university officials. Graduate students at Cornell University currently receive little to no information about sexual assault on campus, other than an optional, sparsely-attended orientation program. This is especially concerning for international students, who comprise the majority of Cornell’s graduate student population and who may, owing to language or cultural barriers, be unaware of their options or reluctant about contacting police. Furthermore, the university should make the information about a third-party resource like the Advocacy Center, which operates a 24-hour hotline, more easily accessible to students as a way to provide survivors more alternatives for reporting incidents in less triggering environments. The Advocacy Center is a comprehensive domestic and sexual violence service agency located in Tompkins County. The director of programming at the Advocacy Center, Louise Miller, told me that currently, Cornell University does not provide any financial support to this agency. The Advocacy Center receives proceeds from fundraising organized by student clubs and events like The Vagina Monologues, hosted by the Women’s Resource Center, but gets no direct contribution from Cornell University. In order to show the appreciation and support for the work the Advocacy Center does by serving a large part of the Cornell community, the University should provide monetary support to this organization.

So what assures Cornellians that their stories will be heard and justice will be served? Cornell University has much to learn from movements and practices taking place in other institutions and communities to ensure a supportive environment for the survivors. At present, Yale generates a unique semi-annual report of complaints of sexual misconduct, which compiles all the reports on sexual assault recorded, some details of the nature of the complaints, and the outcomes of investigations. The aim of this report is to share awareness and involve the community in recognizing the extent of sexual assault so that collectively people strive to eliminate the issue of sexual violence on Yale’s campus. Information is power—and the power provided by information can eventually help transform the culture of victim-blaming around sexual assault and empower survivors to seek justice in ways suitable to them.

Source: Report on the AAU Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct, 2013