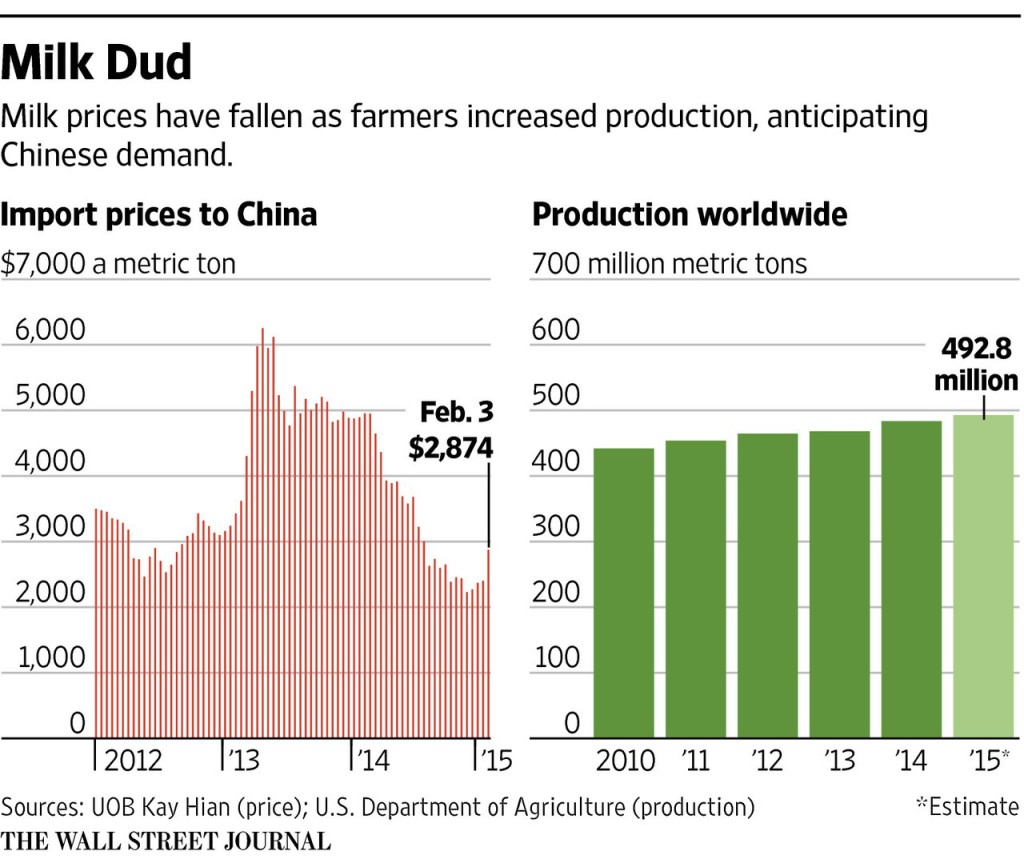

Chinese farmers pouring away milk due to anticipated excess supply of lower-priced and high-quality imported milk. Source: Yap, Chuin-Wei. “Chinese Dump Milk as Prices Fall.” Wall Street Journal. February 19, 2015. http://www.wsj.com/articles/chinese-dump-milk-as-prices-fall-1424385450On April 1st, 2015, the EU milk quotas came to an end. First introduced in 1984, the milk quota allowed each member of the European Economic Community to produce dairy products up to a set maximum volume. At the time, the supply of dairy goods far outstripped demand, and producers that exceeded specified production volumes were subject to a levy. With the removal of the burdensome levy, EU producers are expected to significantly increase production. Additionally, the recent closure of Russian markets due to trade embargos is forcing EU producers to find alternative buyers for the huge volume of excess milk products. In response to the sizable and fast-growing global milk markets in Asia, China has become one of the EU’s targeted markets. However, because of increased imports, the competition in the Chinese milk market will become fiercer. This has serious negative implications for some small-scale Chinese producers.

Originally, the quota was to last for only five years, until 1989, but its elimination was delayed until 2003, and again until 2008 with a range of measures aimed to reach a final “soft landing” by 2015. Considering the prolonging of the policy, the economic implications of its end should not surprise EU milk producers. However, due to the vast differences in production volume among European countries, the abolition of the milk quota received a mixed response. While key producers and exporters from Germany, Holland, and the Irish Republic are preparing for sharp increases in their production, Belgian and French producers have protested the shift in policy, requesting emergency quotas to decrease European milk production. Considering the significant regional production expansion and the current Russian ban on European agricultural imports, decreasing EU milk production may help small-scale producers survive the present drastic drop in prices. With less production efficiency and slimmer profit margins, small-scale European farmers are currently struggling to break even, and volatile prices may drive them out of the market altogether.

The Wall Street Journal. Yap, Chuin-Wei. “Chinese Dump Milk as Prices Fall.” Wall Street Journal. February 19, 2015. http://www.wsj.com/articles/chinese-dump-milk-as-prices-fall-1424385450

Regardless of the quota policy, the EU is a main player in the global milk industry, and has frequently struggled with the dynamic global price of milk. Safety-net policy measures including direct payments from the government to producers and intervention prices still exist. Additionally, the EU has recently established the Milk Market Observatory, which aims to increase market transparency and producers’ awareness of market situations. It was created in an attempt to guide EU producers in seizing global market opportunities through more frequent milk producer meetings and economic analyses of the dairy market. In a press release, the EU Commissioner for Agriculture and Rural Development, Phil Hogan, said, “[The end of the milk quota] is a challenge because an entire generation of dairy farmers will have to live under completely new circumstances and volatility will surely accompany them along the road.”

In the short term, the EU will struggle with market pressures. However, in the long-term, lifting the milk quota will lower the administrative burden, reduce the cost on government regulations, and further enhance the competitiveness of the global milk sector. European Milk Board member, Erwin Schöpges, reflects this attitude. He states, “Today, we need a decrease in European production in order to reach a balance in the market. But when the crisis is over, then we won’t want that system of regulation anymore; when it’s over, we want to be able to keep producing.” Clearly, there is a strong belief that ending the quota policy will lend to growth and more long-run job creation.

Given recent history, the Chinese market is poised to receive EU milk imports. Self-sufficient Chinese dairy firms suffered dramatically after the 2008 milk powder scandal, which led to deep distrust of domestic dairy products and Chinese consumers’ strong preference for imported dairy products, especially infant formula. The preference for imported milk products was so overwhelming that some countries, including Germany, New Zealand, and Australia, implemented restrictions on exporting milk powder. To win consumers’ hearts back and enhance control of raw milk, certain Chinese firms have acquired foreign companies, built closer business ties, and established joint ventures with foreign dairy plants and farms. The Chinese government is also putting significant effort into regulating the safety and monitoring the development of the domestic milk industry. In June 2014, the government announced a policy pushing mergers and reorganization in infant milk powder enterprises. The objective of this plan is to increase the Chinese market share of the top ten domestic companies in the infant formula powder industry to 65% by 2015 and to 80% by 2018.

This will be particularly difficult considering how the coming influx of EU products will intensify the competition in the Chinese dairy industry. Certainly, Chinese consumers can benefit from more dairy products with a wider range of prices. Domestic producers will likely defend their positions by drawing on their solid distribution networks and the high consumer awareness of their brands. The threat from the anticipated flood of imported high-quality milk products at competitive prices from the EU, however, makes it hard to tell who will claim a greater portion of the Chinese market. Understandably, the Chinese government wants a stronger domestic market share, but the tension between these interests and the end of the EU milk quota is likely to crowd small-scale Chinese dairy farmers out of the market.

In the background of this battle for market share, weaker players in the Chinese market are likely to be driven out of business by increased global competition. In fact, since late 2014—even before the end of the EU milk quotas—some Chinese dairy farmers have begun to dispose of milk, slaughter cows, or even close their farms altogether due to the pressures of falling raw milk prices. In China, a global supply surplus and a free trade agreement with Australia precipitated the first fall in prices. With the end of the EU quota, the prices of imported milk products in China will continue to plummet with the expectation of more European milk products entering the market. Because the prices of imported milk products are much lower than the breakeven points of domestic small-scale producers, many dairy farmers have already failed to make a living and gone bankrupt. The situation will likely worsen with increased EU imports.

Given these recent trends in the market, at the beginning of 2015, the Chinese National Department of Agriculture required local governments to support their farmers by offering subsidies and encouraging domestic companies to purchase local dairy goods. The government implemented these polices in an effort to increase sales and stabilize the average unit price of local milk. However, the practice of dumping milk persists. Indeed, considering lower prices and consumers’ strong preference for imported raw milk versus the comparatively small production scale and high cost of local milk, such support undermines and even contradicts the goal of increasing the market share of local companies. Rather than price control or subsidies, farmers need more support through market predictions, value-adding technology, management education and, most importantly, a safety- net system to maintain a normal standard of living. These systems are in place in the EU, and are a more logical long-term solution for market volatility than incentivizing continued market share goals and small-scale production. It is economical for small and independent farmers to exit the market and for large firms to purchase foreign milk productions instead. Although leaving the market is initially negative for small-scale producers, implementing safety net policies will provide flexibility in their choice to exit the market. This would be a better expenditure of the Chinese government’s efforts and resources. The paradox between temporary assistance and the long-lasting lack of safety net policies for dairy farmers will not only slow the modernization of Chinese dairy industries but also prevent any improvement in the living conditions of Chinese farmers.

Although price fluctuation and volatility has appeared after lifting EU milk quotas, many are optimistic about the growth and jobs the policy’s lift will bring to the EU. However, China does not currently enjoy the presence of safety net policies for producers. As a primary importer of the EU’s dairy goods, China needs to prepare for the incoming fierce competition. The government has considered the uncertainty of whether the domestic companies can keep and even enlarge their market share. However, rather than focus on market share, the Chinese government needs to design related policies more systematically and sustainably to modernize the dairy industry and protect the wellbeing of small-scale farmers. This can be accomplished through implementing safety net polices for Chinese dairy producers similar to those in the EU. Neglecting the need for such polices will only result in more spilt milk.