Photo by Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash

Written by: Adam Terragnoli

Edited by: Kristen Angierski

The mapping software, Plectica, was used to create the maps included in this analysis. To access the full map: http://bit.ly/STestMap

Introduction

On any given school day in the United States, over 15 million high school students attend over 100,000 schools.[1] Almost three-quarters of these students will go to one of the 3,500 institutions of higher education after graduation.[2] For many, securing a spot at the college of their choosing is a long-awaited goal of their education. But many colleges and universities across the country receive more applications than they can accept.

Once thought of as the “gold standard for ensuring student quality,” a “common yardstick,” and a “great equalizer,” standardized tests measure academic achievement in a controlled and consistent way.[3] These tests are supposed to measure student abilities irrespective of which high school they attended. In theory, grade inflation is mitigated, and gifted students from low-performing schools can stand out. Although this may be the case in certain situations, manifold flaws have been documented over time, including bias against social-class, ethnic, regional, and other cultural differences.[4]

A recent push for “test-optional” or “test-flexible” admissions has gained traction across the US. A test-optional policy differs from a test-flexible policy because the former does not require a student to submit SAT/ACT scores during the admission process, while the latter allows students to submit a variety of scores, including SAT Subject Tests, Advanced Placement (AP) tests, and International Baccalaureate (IB) tests. These options de-emphasize a single exam’s result, providing a more comprehensive student profile.[5] Standardized tests have been criticized for creating an unfair playing field for certain populations, weakening the content being taught in schools, and for being an inaccurate predictor of college readiness.[6] That last factor, that standardized tests do not accurately exhibit a student’s readiness, will be explored through the following systemic analysis.

The Impetus for Standardized Testing

In 1782, Thomas Jefferson described the path for those who wanted to pursue higher education, declaring that “the best geniuses will be raked from the rubbish” and “chosen for the superiority of their parts.”[7] For nearly 150 years students across the United States were admitted into colleges and universities based on an array of admissions criteria. However, during this time, only a number of students chose to pursue higher education. In 1900, roughly 2 percent of 17-year-olds continued their education past secondary school to receive a college degree. Those applying to colleges were faced with a litany of admission requirements which beget the need for a standardized process. In 1926, the first standardized test for college admission, the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT), was administered to about 8,000 students. Later, in 1959, a competitor – American College Testing (ACT) – joined the standardized testing market. Standardized tests have become ubiquitous, with millions of students sitting for an exam each year to meet the admission requirement at nearly 90% of US colleges.[8] In many states, taking a standardized test is required by law; for example, all 53,000 high school juniors in South Carolina are required to take an ACT.[9][10] The use of standardized exams is not confined to US higher education, nor did its prolific use begin in 1926. Rather, standardized tests can be traced back to the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) in China where exams were used to create an intellectual meritocracy and discourage nepotism.[11]

Systems Thinking Applied

In their seminal book, Systems Thinking Made Simple, Drs. Derek and Laura Cabrera describe four simple rules of systems thinking.[12] These rules can be summarized using the acronym “DSRP,” which stands for Distinctions, Systems, Relationships, and Perspectives. Systems thinking is an emergent property of DSRP rules, and can help structure thinking when conducting systemic analysis. It is important to understand the four rules as they exist, in order to apply them to the standardized testing system.

D: “Distinction” rule states that “any idea or thing can be distinguished from the other ideas or things.”

S: “Systems” rule states that “any idea or thing can be split into parts or lumped into a whole.”

R: “Relationship” rule states that “any idea or thing can relate to other things or ideas.”

P: “Perspectives” rule states that “any thing or idea can be the point or the view of a perspective.”

It is important to understand that there is no linear progression of the rules; that is, there is no starting or ending point. The rules can be mixed and matched, viewed independently or combined to form a holistic picture.

What is a Standardized Test?

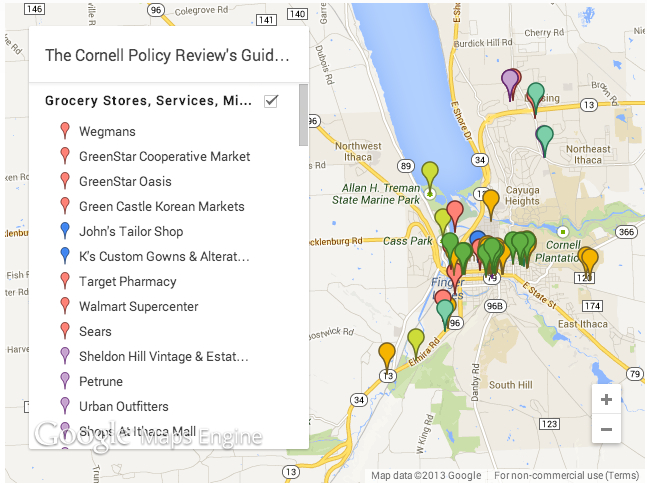

Over the course of an individuals’ K-12 education, tests are used to assess the content learned in a given course. It is important to distinguish between school tests (e.g., unit test, spelling test, etc.) often made by teachers, and standardized tests. To do so, it’s crucial to understand the system (part/whole) and the relationship between the parts. Figure 1 breaks down standardized tests into their most basal elements. The phrase “standardized test” is, in fact, a system containing two parts (words), a verb and a noun, that make up a whole. It’s necessary to understand that the verb, “standardized” frames the noun, “test.” What distinguishes a standardized test from a teacher-made test is the consistency of the question bank, and the uniformity in the grading rubric. Both of these conditions allow for the comparability of scores across test takers. Standardized exams are beneficial when you want to administer a test to a large population of people. A teacher-made test could be a standardized test if it adheres to these same principles.

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework of Standardized Tests

The Standardized Test Equation

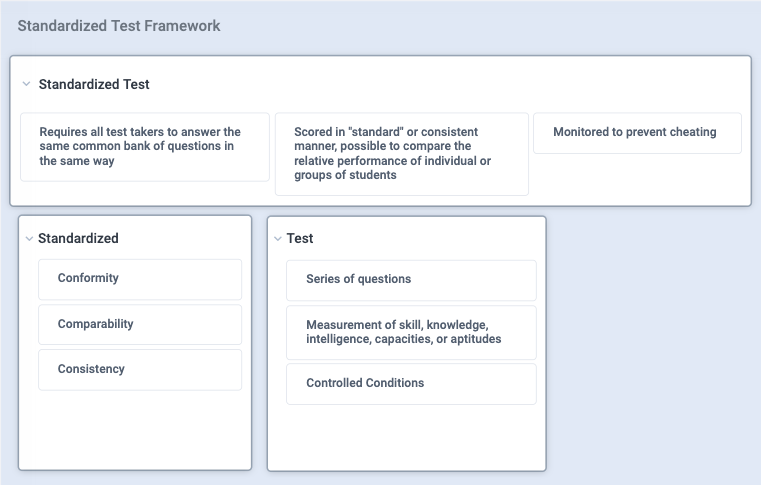

There is a phrase in the Organizational Design field that posits “system structure determines behavior,” meaning that in order to understand how or why an individual or a group are producing a certain outcome, you must look to the structure of the system they are operating within.[13] The same principle is applied when creating standardized tests. Test creators must construct a system that will enable students to take their tests. Before delving into this system it’s important to acknowledge an assumption (or bias) that is present when discussing tests – that they are useful. At present, standardized tests operate under the assumption that they are useful for college admissions if the test would admit students who would otherwise be rejected, and reject students who would otherwise be admitted.

Standardized tests can be useful when testing a large population of individuals, especially when those individuals are dispersed across a large geographic area. Test fairness is also essential. The summation, or relationship, between fairness and scale is an inextricably connected relationship that results in a legitimate and functional test. The absence of either of those components could threaten the test’s usefulness and/or validity. Therefore, the equation for standardized tests (in Figure 2) can be expressed as:

Fairness + Scale = Standardized Test

Figure 2: Standardized Test Equation

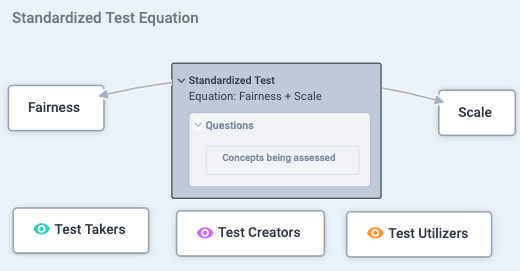

The Pathway to College

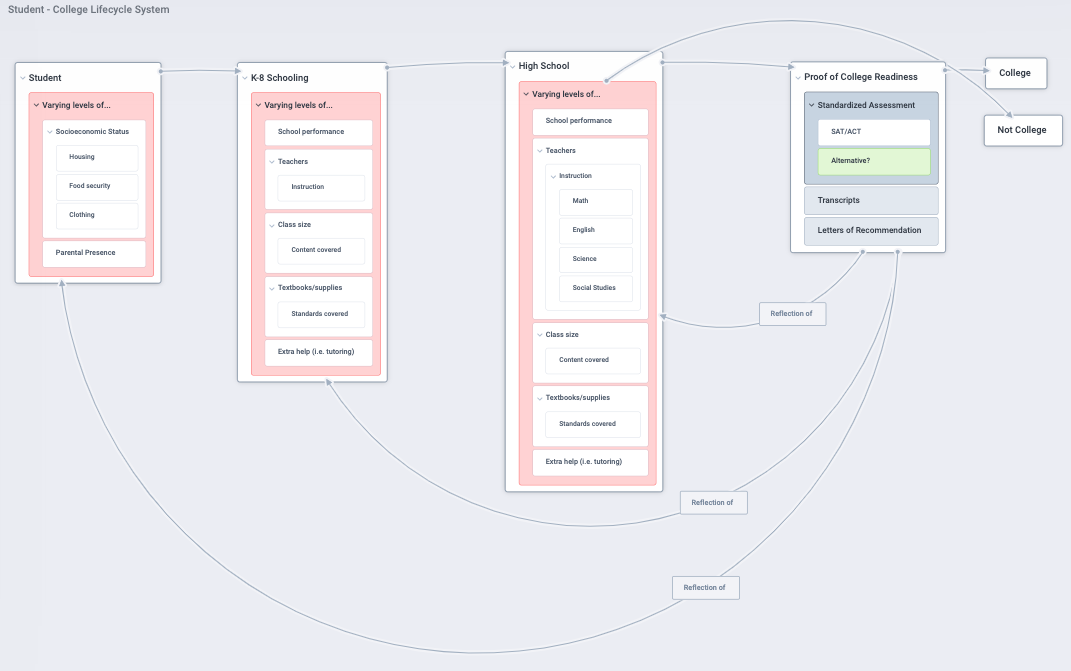

Primary and secondary education in the United States follows a linear progression, beginning in Kindergarten and continuing through grades 1-12 each year, termed “K-12.” There are occasional deviations from that trajectory, such as skipping or failing a grade. Moreover, there are compulsory education laws that mandate children and young adults attend school, which vary on a state-to-state basis.[14] Figure 3 shows a high-level view of a student and the K-12 system.

Figure 3: Student – College Lifecycle System

Any student who wants to attend college needs to prove that they are ready to meet the rigorous standards of a given institution. There are myriad ways a student documents readiness, such as submitting course transcripts, letters of recommendation, and standardized test scores. Other supplemental materials such as school-specific questions or essays can also be included. Figure 4 shows the scaffolded nature of proving college readiness and displays a more granular view of the previous figure, identifying additional part/whole systems. The map not only shows the parts, but recognizes their variability. This map is, in essence, a framework; one could input student information and data to paint a complete picture of an individual’s profile. If done, no two maps (i.e. students) would be identical (other than siblings, potentially). In other words, there is a distinction among all of these frameworks when applied to individuals. The map highlights the relationship among the student, K-8, and high school boxes to proof of college readiness. All three boxes, and the parts contained within, are (ideally) reflected when a college is determining admission. At the crux of Figure 4 is identifying and acknowledging the many obfuscatory and variable factors that comprise the K-12 system. Consequently, it is the obfuscatory and variable conditions that beget the need for standardized exams.

Figure 4: Granular view of Figure 3: Student – College Lifecycle System

Feedback Loop

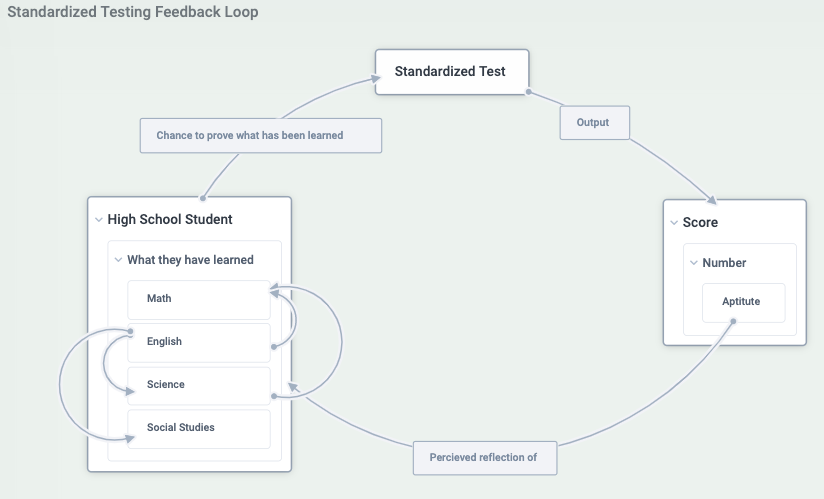

A more complete analysis of college readiness and admissions tests requires context (i.e. information and structure) that addresses the concept of “aptitude.” First, it must be noted that there is not a consensus among the academic fields when defining aptitude. Some common phrases widely associated with the concept of “aptitude” are readiness to learn, motivation, talent, and aspects of personality, among others.[15] Definition differences notwithstanding, aptitude was the original stated output of the SAT. Figure 5 shows the high school – SAT feedback loop.

Figure 5: High School – SAT Feedback Loop

Originally, the A in SAT stood for “aptitude” but then switched over time to become “assessment.”[16] This is an important distinction since one must wonder if the name change was made because of the public’s perception, because the test was evolving, a mix of both, or other reasons. Although the rationale for the change was not provided, the end goal of the exam remained constant – determining which individuals were likely to succeed in a particular environment.

What are we (actually) testing?

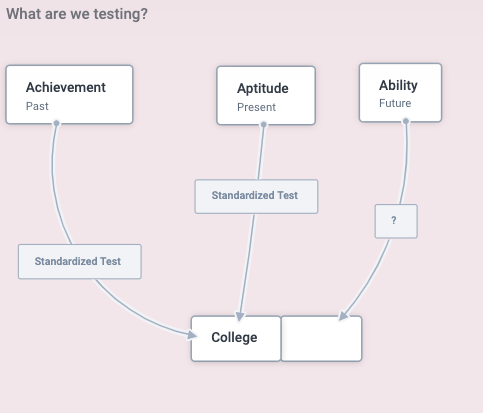

“College readiness” is a hypothesis based on the distinction between aptitude, ability, and achievement. There is great disagreement among communities, namely psychologists, as to the distinction among the three terms. Often, the three are used as synonyms, when there is in fact a distinction needs to be made.[17] Achievement tests are designed to assess how much a person has learned (past tense) a specific body of knowledge. The difference between aptitude and ability is more nuanced. Aptitude tests are designed to assess an individual’s ability to learn, whereas ability tests have similar elements: they assess knowledge and skill sets that have been acquired over a long period of time, but also have a predictive quality, hypothesizing continued growth into the future. If these three concepts are simply defined as: achievement – past, aptitude – present, ability – future, then the current standardized testing system assesses a combination of achievement and aptitude in order to predict ability. Figure 6 maps these distinctions, systems, and relationships as they apply to college admission. Some testing systems claim to be able to test abilities as defined here, which will be discussed later. One example would be a test based on Howard Gardner’s theory of Multiple Intelligences.[18]

Figure 6: Achievement vs. Aptitude vs. Ability

An Alternative System

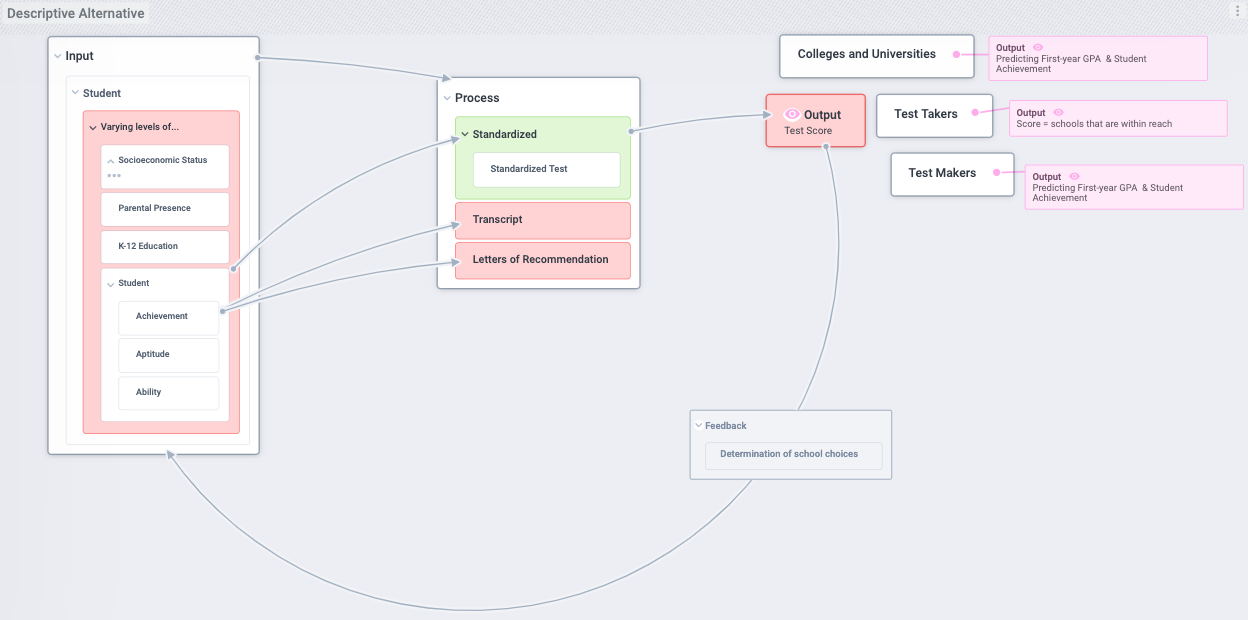

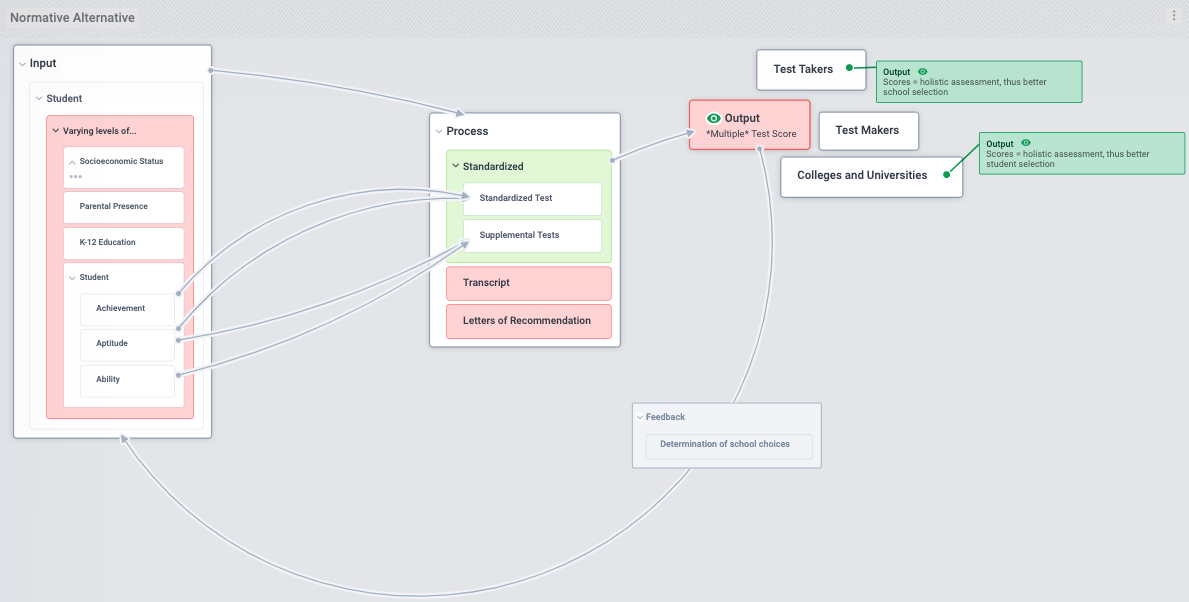

One of the central goals of the admissions process is to ensure the selection of qualified students who will be able to thrive in a particular academic setting. Indeed, one of the assumptions outlined at the outset, and assumed by the testing system at large, is that tests are only useful if they admit students they otherwise would not, and reject students they otherwise would admit. From that vantage, one must question if the current standardized testing system meets that aim. There is a litany of evidence that suggests flaws exist in standardized tests, namely that the test outcomes are closely correlated with wealth and are biased against those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.[19][20] Additionally, it is important to note that from the perspective of the college or university, the tests are ostensibly useful at predicting first-year GPA, but not beyond. This perspective is also understood by the test creators.[21] Figure 7 shows a descriptive view of the system.

Figure 7: An Alternative System – Descriptive

One alternative to the status quo is continuing the trend of test-optional and test-flexible policies; another solution is supplementing them by reverse-engineering the desired outcome. As stated previously, colleges and universities want to admit highly qualified students that will have success in their academic setting. If the current tests only loosely predict first-year success, it could prove useful to elide additional insights. These insights might provide a more complete picture of a student’s “ability” over the course of their college career; the extent of that growth is unknown. One project, named “The Kaleidoscope Project,” attempted to ameliorate this concern.

The project placed questions on a college application with the goal of assessing wisdom, analytical and practical intelligence, and creativity.[22] The concept behind the approach leverages the balance theory of wisdom, which states that “wisdom is the application of intelligence, creativity, and knowledge for the common good” and strives towards this goal by “balancing intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extra-personal interests over the long and short term.”[23] The assessment allows students to demonstrate their creative abilities by writing short stories, demonstrate analytical skills by writing alternative endings to history (e.g., “What if Rosa Parks had given up her seat?), demonstrate innovation by creating a product or advertisement, demonstrate analytical skills by asking the student to persuade their friends of something they hold true, and demonstrate wisdom by asking how a passion they have could be applied to a common good. One of the stated goals of the project is to “reconceptualize” applicants, and therefore offer an alternative to standardized tests. In their pilot year, the project found that average academic quality of applicants rose. The process yielded admission of students who were more qualified, in a “broader” way – more criteria were assessed. When surveyed, applicants reported that they believed the application gave them the opportunity to demonstrate their uniqueness. Figure 8 shows this normative alternative to the process.

Figure 8: An Alternative System – Normative

Conclusion

Increasing the number of tests, albeit potentially useful, could have downsides. Making the process more onerous, burdensome, or harder could continue to disadvantage students from certain backgrounds. Downsides notwithstanding, it is a worthy endeavor to continue to innovate the college admission process, a process that has remained relatively unchanged throughout time.[24] The current system for admitting students to colleges and universities across the country has been in place for almost one hundred years. By experimenting with new and innovative ideas that improve student application profiles, feedback can be harnessed, and the system can improve.

References

- The NCES Fast Facts Tool provides quick answers to many education questions (National Center for Education Statistics). (n.d.). https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=372 ↑

- Selingo, Jeff. “How Many Colleges and Universities Do We Really Need?” The Washington Post. WP Company, April 29, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2015/07/20/how-many-colleges-and-universities-do-we-really-need/. ↑

- Soares, Joseph A. Ed. Sat Wars: The Case for Test-Optional College Admissions, 2012 ↑

- Strauss, Valerie. “Analysis | 34 Problems with Standardized Tests.” The Washington Post. WP Company, April 18, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2017/04/19/34-problems-with-standardized-tests/. ↑

- Whitlock, A. Is your college on the list of those dropping the ACT and SAT for admissions? NewsWeek, October 17, 2019 Retrieved from https://www.newsweek.com/colleges-are-dropping-act-sat-requirements-look-schools-that-dont-use-test-scores-1465062. ↑

- Atkinson, R. & Geiser, S. Reflections on a Century of College Admissions Tests. From Soares, J. SAT Wars: The Case for Test-Optional College Admissions. 2012. ↑

- Notes On Virginia. viii, 388. Ford Ed., iii, 251. (1782.), as quoted in The Jefferson Cyclopedia, a comprehensive collection of the views of Thomas Jefferson, Ed. John P. Foley, Funk and Wagnalls Company, New York, 1900, page 275. ↑

- Zwick, R. Rethinking the Sat The Future of Standardized Testing in University Admissions. London: Taylor and Francis. 2013 ↑

- Adams, C. J. In Race for Test-Takers, ACT Outscores SAT-for Now. EdWeek. February 20, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2017/05/24/in-race-for-test-takers-act-outscores-sat–for.html. ↑

- South Carolina Department of Education. (n.d.). South Carolina High School Class of 2018 ACT Performance Slips in ACT Report Retrieved from https://ed.sc.gov/newsroom/news-releases/south-carolina-high-school-class-of-2018-act-performance-slips-in-act-report/. ↑

- Strauss, V. How the first standardized tests helped start a war – really. April 22, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2012/12/03/how-the-first-standardized-tests-helped-start-a-war-really/. ↑

- Cabrera, Derek. & Cabrera, Laura. Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems. 2018 ↑

- Senge, Peter M. The Fifth Discipline. London: Random House Business, 2006. ↑

- Compulsory school attendance laws, minimum and maximum age limits for required free education, by state (2017) National Center for Educational Statistics https://nces.ed.gov/programs/statereform/tab5_1.asp ↑

- Doughty, C.J. Cognitive Language Aptitude. Language Learning, 69: 101-126. 2019. doi:10.1111/lang.12322 ↑

- Lohman, D. Aptitude for College: The Importance of Reasoning Tests for Minority Admissions ↑

- Achievement, Aptitude, and Ability Tests (2004) Retrieved from: https://psychology.iresearchnet.com/counseling-psychology/career-assessment/achievement-aptitude-and-ability-tests/ ↑

- Multiple Intelligence – Howard Gardner. from https://web.cortland.edu/andersmd/learning/MI%20Theory.htm (n.d.) ↑

- Rosner, J. Quantifying the Unfairness Behind the Bubbles. From Soares, J. SAT Wars: The Case for Test-Optional College Admissions. 2012. ↑

- Crouse, James and Dale Trusheim. The Case against the SAT. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988. ↑

- Perez, C. Reassessing College Admissions: Examining Tests and Admitting Alternatives. 2004. ↑

- Sternberg, R. College Admission Assessments: New Techniques for a New Millennium. 2004. ↑

- Ibid. 20 ↑

- Riccards, Michael P. The College Board and American Higher Education. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, 2010. ↑