Graphic by Marla Munkh-Achit

Pittsburgh’s Growing Flood Risk: An examination of recent trends and how integrated watershed management can help

By Austin Reid

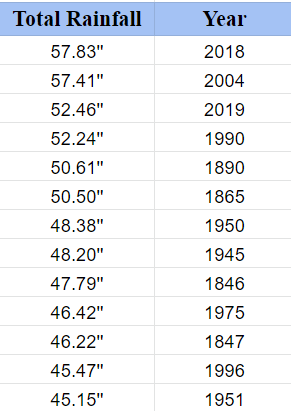

2018 marked the wettest year in Pittsburgh’s history.[1] The nearly 58 inches of rain over the course of the year swelled waterways and contributed to flash floods, inundated basements and landslides in many areas across Allegheny County. Heavy rains persisted into 2019 and resulted in closed roadways, impacting at least one University of Pittsburgh Medical Center campus.

According to the First Street Foundation, a Brooklyn-based nonprofit dedicated to communicating the risks of flooding, 17 percent of properties in Pittsburgh are at risk of flooding. Over the next 30 years, this total will increase by 3 percent to 23,944 properties.[2]

In response to increased flooding incidents in and around Pittsburgh, eleven municipalities have partnered with the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority (PWSA) to implement an integrated watershed management plan (Master Plan). However, Allegheny County is home to 130 self-governing municipalities, the second-highest total out of any county in the United States.[3] Therefore, for the Master Plan to play an effective role in mitigating flood risk, it will be necessary to implement a unified watershed management effort that engages municipalities from rural, suburban, and urban areas of Allegheny County. At present, only 8.5 percent of municipalities have been invited to collaborate in flood mitigation efforts, which is insufficient to address the growing risks of flooding in Allegheny County.

Recent Rainfall Patterns. Around 22 percent of Pittsburgh’s 50 wettest years on record have occurred since 2000.[4] The year 2004 was particularly wet, and flooding damaged at least 120 properties in Allegheny County. Most of this flooding occurred along Chartiers Creek. The boroughs of Carnegie and McKees Rocks west of downtown Pittsburgh were also particularly affected.[5] To the north, Etna, located along the Allegheny River, was also significantly impacted. It is likely that additional properties would have been damaged in the 2004 floods if not for levees built after the St. Patrick’s Day Flood of 1936.[6] More recently, in August 2021, remnants of the tropical storm Ida flooded roadways and took down power lines.[7]

Table 1: Wettest Years in Pittsburgh on Record

Source: National Weather Service 2021

Ongoing PWSA Projects. Recognizing that recent heavy rainfalls have routinely overwhelmed Pittsburgh’s sewer system, PWSA is in the process of installing new stormwater infrastructure across participating areas. This infrastructure combines both natural vegetation and constructed channels to hold water back from entering sewer systems at once.[8] PWSA is also investing millions in creating a green infrastructure project in the Four Mile Run Watershed south of Shadyside. It is hoped that these projects can alleviate flood damage in the Pittsburgh area and decrease overflows of raw sewage into the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio rivers.[9]

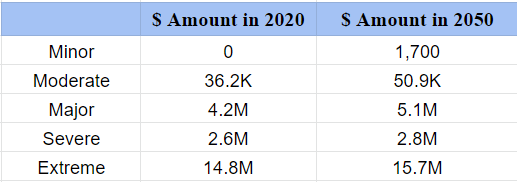

Future Risks. It is estimated that in 30 years total annual flood damages in Pittsburgh will rise by nine percent to $23.6 million.[10]

Table 2: Estimated Flood Damages in Pittsburgh by Severity of Flood

Source: First Street Foundation 2020

Neighborhoods that will be particularly impacted include Central Lawrenceville, Downtown, East Allegheny, and the Strip District. Another risk facing Pittsburgh is the aging levee system that holds back potential floods in the Ohio River Basin. As of 2018, the average age of levees in Pennsylvania is 48 years, and one-third are older than 50 years..[11]

County-wide Flood Mitigation. Recent floods have demonstrated that rural and suburban areas outside of Pittsburgh have an especially high risk of inundating. Yet, the majority of these areas are not engaged in existing PWSA watershed management efforts. Further, flood risk is also on the rise throughout the United States. [12] Across many states, county-wide flood mitigation efforts are a key tool in adapting to changing rainfall patterns and reducing flood damage. The success of these united efforts in two states, North Carolina and Texas, offers some examples for Allegheny County. Originating in 1993 in Mecklenburgh County, the Charlotte-Mecklenburgh Storm Water Services develops and implements a comprehensive flood mitigation plan involving seven municipalities and the county government[13]. As a result, 77 percent of municipalities in the county participate. This county-wide collaboration has resulted in uniform educational initiatives focusing on flood mitigation that engage a wide range of residents and create regular development guidelines for properties located in flood-prone areas. In Harris County, Texas, a county-wide Flood Control District has been in existence since 1937. This District serves as a coordinating organization and information link for all 35 floodplain administrators within Harris County. The organization also helps to secure vital federal funding for flood-mitigation efforts.

Recommendations. We can avert some of the damages rendered by flooding if the City of Pittsburgh and PWSA intensify efforts to partner with smaller municipalities as part of existing watershed management efforts. The ultimate goal of these efforts ought to be implementing a county-wide Master Plan for watershed management. This expanded Master Plan should continue to combine restoring natural vegetation with constructing drainage infrastructure to channel and better control the flow of rainwater. While the current efforts by PWSA to address flooding are to be commended, they remain piecemeal and are not currently engaging the vast majority of municipalities in Allegheny County. As long as municipalities in rural and suburban areas of Allegheny County do not participate in a unified watershed management program, flood mitigation efforts will be hindered.

Engaging smaller municipalities in flood mitigation efforts also aligns with recent trends that promote greater integration among Allegheny County’s municipalities. Over the past twenty years, numerous rural and suburban municipalities, many of which have their roots as company towns in the late 1800s, have come together to share some services, such as police and fire departments[14]. Collaboration between municipalities also reduces the costs associated with implementing numerous flood mitigation plans that may conflict if drafted independently. The partnership between larger and smaller municipalities also better ensures that the smallest boroughs have the resources to mitigate flood disasters. This is especially important for boroughs such as Chalfant, West Elizabeth, and Pennsbury Village, that are home to fewer than 1,000 people. Many of these locations face difficulty when applying for specialized government grants or filling elected positions[15].

Another key to expanding participation in the watershed management program is to engage more county residents in flood mitigation efforts. To date, mitigation efforts have focused almost exclusively on public lands and infrastructure, leaving private properties and many residents under-utilized. Getting more homeowners and renters involved in flood mitigation is a major way to increase awareness of the watershed management program and, in turn, its adoption in more areas of Allegheny County. One low-cost way to engage the general public is to conduct an information campaign to encourage Allegheny County residents to plant rain gardens in their yards. These gardens work to alleviate flood risk by retaining higher water levels and releasing moisture into the ground over a longer period. For a typical residential property, a rain garden can be planted for $3 to $5 per square foot, and there are minimal maintenance costs[16]. Starter seed packs can also be distributed. Along with information about rain gardens, program literature can encourage residents to contact their local representatives and encourage their municipality’s adoption of the Master Plan. Calls should also be scheduled with local boroughs and township officials to explain the Master Plan and why its adoption is important.

It is also recommended that a county-wide watershed management plan include a renovation schedule for aging flood mitigation infrastructure, including the most prominent levees. This renovation plan can be best supported through a collaboration between the City of Pittsburgh and surrounding municipalities. Many levees in Allegheny County are nearing the end of their anticipated operational life, but critical repairs have not been included in the existing Master Plan. Funding for these repairs can be partially supported through grants available through the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) FEMA initiative. Additional funding could be obtained through the Marcellus Legacy Fund, a state-supported grant program dedicated to supporting flood mitigation initiatives.

Risks. A risk associated with expanding the Master Plan to include more municipalities is that deadlock could be caused by the inclusion of dozens of more interests at planning meetings. Yet, these concerns also exist when municipalities are left out of the planning process. For example, municipalities may take to other means, such as appeals to the county government, to voice their concerns about flood mitigation plans. Early on, efforts to recruit more municipalities into the Master Plan can focus on those adjacent to creeks and rivers and those which are already collaborating with neighbors in other areas, such as ambulance and fire services. The effective inclusion of these municipalities can help to build trust in the Master Plan, among other areas.

Citations.

- Smeltz, Adam. “Out with a Splash: Pittsburgh Area Closes 2018 with Precipitation Record.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 31, 2018. https://www.post-gazette.com/local/region/2018/12/31/Pittsburgh-rainfall-precipitation-2018-record-New-Year-forecast-First-Night-fireworks/stories/201812310091. ↑

- First Street Foundation. “Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.” 2020. https://floodfactor/city/pittsburgh-pennsylvania/4261000_fsid. ↑

- Lucchino, Frank. “In Allegheny County, Towns Increased from 7 Townships to 130 Municipalities.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 25, 2017. https://www.post-gazette.com/uncategorized/2004/08/08/In-Allegheny-County-towns-increased-from-7-townships-to-130-municipalities/stories/200408080224. ↑

- Smeltz, Adam. “Out with a Splash: Pittsburgh Area Closes 2018 with Precipitation Record.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 31, 2018. https://www.post-gazette.com/local/region/2018/12/31/Pittsburgh-rainfall-precipitation-2018-record-New-Year-forecast-First-Night-fireworks/stories/201812310091. ↑

- First Street Foundation. “Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.” 2020. https://floodfactor/city/pittsburgh-pennsylvania/4261000_fsid. ↑

- First Street Foundation. “Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.” 2020. https://floodfactor/city/pittsburgh-pennsylvania/4261000_fsid. ↑

- Lauer, Hallie. “Roads Flooding across Pittsburgh Region as Remnants of Ida Dump Torrential Rain.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://www.post-gazette.com/news/environment/2021/08/31/pittsburgh-weather-hurricane-ida-remnants-southwestern-pennsylvania-forecast-allegheny-county-westmoreland/stories/202108310148. ↑

- Pittsburgh Water & Sewer Authority. “Stormwater About.” 2021. https://www.pgh2o.com/your-water/stormwater. ↑

- Zuidema, Teake. “Raw Sewage Flows into Pittsburgh’s Rivers. Is There an Environmentally Friendly Fix That Won’t Break the Bank?” PublicSource News for a better Pittsburgh, December 6, 2017. https://www.publicsource.org/will-green-or-gray-infrastructure-solve-the-problem-of-raw-sewage-running-into-the-pittsburgh-regions-rivers/. ↑

- First Street Foundation. “Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.” 2020. https://floodfactor/city/pittsburgh-pennsylvania/4261000_fsid. ↑

- American Society of Civil Engineers. “Levees.” 2018. https://www.pareportcard.org/PARC2014/downloads/PA_2014_RC_Levees.pdf. ↑

- Varanasi, Anuradha. “Increasing Numbers of U.S. Residents Live in High-Risk Wildfire and Flood Zones. Why?” State of the Planet (blog), January 22, 2021. https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/01/22/high-risk-wildfire-flood-zones/. ↑

- City of Charlotte Government. “Flood Mitigation Program Overview,” 2021. https://charlottenc.gov. ↑

- Bucsko, Mike, and Ed Blazina. “In Allegheny County, Towns Increased from 7 Townships to 130 Municipalities.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 8, 2004. https://www.post-gazette.com/uncategorized/2004/08/08/In-Allegheny-County-towns-increased-from-7-townships-to-130-municipalities/stories/200408080224. ↑

- Lucchino, Frank. “In Allegheny County, Towns Increased from 7 Townships to 130 Municipalities.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 25, 2017. ↑

- Naturally Resilient Communities. “Rain Gardens .” 2017. http://nrcsolutions.org/rain-gardens/. ↑