Source: Kaique Rocha

By Giovanni J.A. Ugut and Alexandra Pfaffle

COVID-19 and SME: Divergence from Large Companies

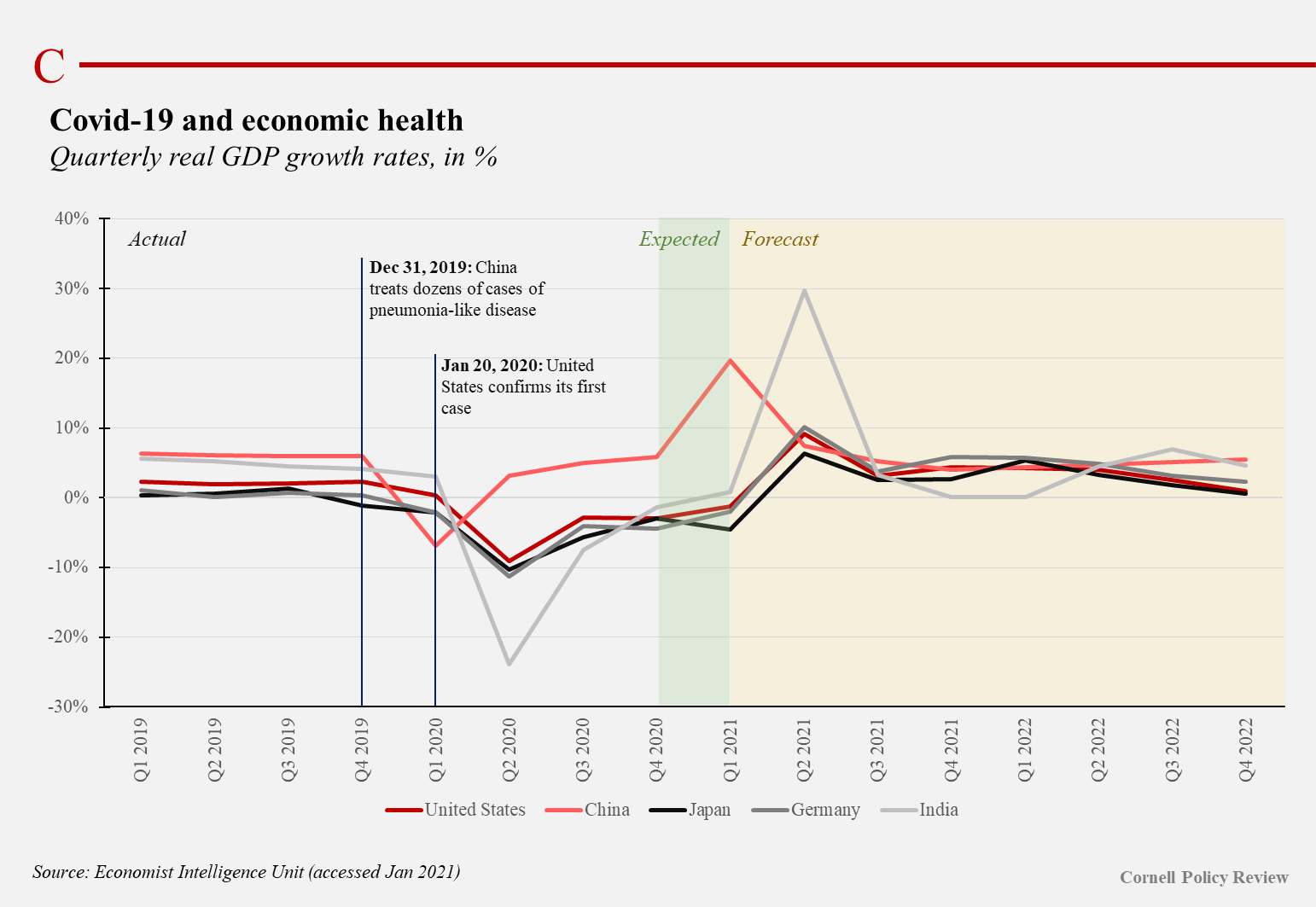

As COVID-19 outbreaks ravaged through countries, most governments enacted various public-health policies, such as social distancing and attendance restrictions. These policies have slowed the wheels of the economy, as once-commonplace transactions are disrupted. Data from the Economist Intelligence Unit shows that the top five G20 countries, the world’s 20 largest economies, had a dramatic decline in real GDP growth in 2020.[1]

Worryingly, the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic will concentrate industry power, further existing divides, and exacerbate income inequalities across industries, firms of different sizes, and workers. Groups structurally disadvantaged pre-pandemic will be at risk of missing opportunities and pathways in the economic recovery process – freezing them out of today’s and tomorrow’s economy.[2] This is also known as a K-shaped economic recovery, an entirely possible scenario as small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are disproportionately affected by the pandemic compared to their larger counterparts. Statistics from Oxxford Information Technology, a Saratoga, NY-based company, show that as of August 2020, more than 1.4 million small businesses have shuttered or temporarily suspended their operations.[3] This is because SMEs are often delayed in digital adoption despite making up around 50-60% of added economic value, whilst employing on average around 67% of the total workforce in OECD countries, a group of mostly high income countries. The digital divide has generated inequalities through an enormous increase in rents, economies of scale, reduced costs, and increased profits for investors, top managers, and large corporations.[4]

COVID-19 and SME Policy Responses

Many governments have enacted crisis management policy responses such as wage and income support, grants, and subsidies to counter this. As an example, as part of the $2.2tn CARES Act which passed in early March 2020, the American government provided $729bn to small businesses through its Payment Protection Program (“PPP”) to preserve employment retention and cover operational costs.[5] The program is an implicit wage subsidy offered through forgivable loans delivered by private banks and the government. While the Government Accountability Office did find the PPP susceptible to fraud risks as a result of the loan-granting process’ being streamlined, the program itself is estimated to have achieved increases in the level of employment in eligible firms by raising private American employment by around 2% – 4.5%, or between 1.4 and 3.2 million jobs.[6] However, the PPP was only designed for the short-term, with a quick economic recovery in mind – this is especially true when the maximum PPP loan drawdown for eligible SMEs was 2.5 months’ worth of average payroll.[7],[8]

Alone, wage subsidies may prove to be too costly and unsustainable given the increasing number of lockdowns in cities due to poor public health conditions, such as rising infections and slow vaccine rollout, and an over-reliance on the legislative bodies to pass large stimulus packages. Existing structural root causes of economic inequality need to be addressed for wage subsidies to be truly able to stimulate aggregate demand.

Digitization is a potential avenue. According to a 2018 Google-commissioned study by Deloitte, digitization helped American SMEs increase revenues by unlocking access to new customers – a much needed approach given the constant oscillation between lockdowns and re-openings. Despite these benefits, the same Deloitte study found that around 80% of American SMEs are not taking full advantage of digital tools and new opportunities. This hesitance on the part of SMEs is mainly driven by a lack of financial resources, a lack of awareness, and a lack of technical skills.[9]

SMEs’ Financial Woes

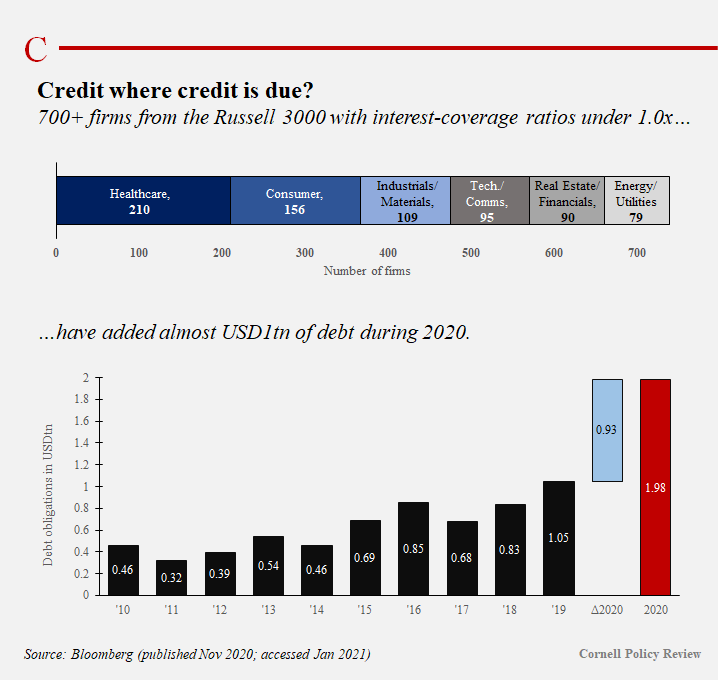

In a bid to remain solvent and resilient amidst the pandemic, businesses found it imperative to conduct transformations to their operations to adhere to the prevailing public health guidelines such as social distancing. However, this need is not as pressing for larger companies. This is because some companies – often larger – have either more COVID-19-resilient business models, such as those found in the tech industry, or have the necessary cash balances or access to funding to either reinvent themselves or, by rolling their existing obligations, live to fight another day. According to Bloomberg, as of the end of 2020, around 739 firms of the Russell 3000 index did not earn enough to cover their interest expenses and owed $1.98tn of debt; this represents a significant increase compared to the 513 firms and $1.05tn owed from the previous year.[10]

This kind of capital misallocation ties up much-needed credit in otherwise unproductive firms and in the economy and crowds out the few SMEs that do have access to the capital markets. This situation is all the more pressing given that the average SME only has a cash buffer—a measure of days a business can pay its cash outflows where its cash inflows stop— of 27 days, as per a JP Morgan Research Institute study on 597,000 small businesses.[11] SMEs’ dire financial situation is further compounded by an alarming retrenchment of the banking industry’s ground operations, from around 36 branches per 100,000 Americans in 2009 to 31 branches per 100,000 Americans in 2017.[12]

Digitization: Achieving SME Resilience

A key driver of the lack of financial inclusion of SMEs is the information asymmetry that exists between SMEs and financial institutions. This asymmetry raises the costs and risk of a financial transaction and is exacerbated at times of economic downturns.[13] Here, governments must devise initiatives that foster data-rich environments by adopting technology such as the Internet of Things and FinTech, which can convert unstructured operational data to creditworthiness insights. A possible approach is to fund digital innovation to better improve loan underwriting standards. Funded companies can note the use of alternative data sets, as commonly found in the developing world, or take a novel AI or Machine Learning-based approach with thousands of potential credit metrics, as is the case with the U.S. company Zest AI.[14] Through these improvements, financial institutions may find an acceptable substitute for traditional financial statements, a streamlined lending process, and increased profitability through decreased credit risk costs.

Should SMEs’ core operations need to be overhauled, for reasons such as a refocus of product offering or realignment to health protocols, tailored financing facilities must be made readily available to encourage the necessary capital expenditure. SMEs are known to prefer grants and equity financing.[15] This is primarily driven by concerns related to their ability to repay loans and an aversion to adding more debt onto their balance sheets.9 However, making equity investments may not be feasible given the number of SMEs. Grants may be possible in countries with more financial power; however, poorer countries may be forced to prioritize larger companies as it is more economically valuable to give them grants. Governments with enough financial capacity and political capital can partner with the financial services industry to provide innovative financing structures. An example is a grant-financing structure whereby banks can charge a low interest rate on the non-grant portion of the credit facility.[16] Such a structure allows banks to increase the amount offered as unexpected loss risk has been minimized; this protects banks from additional credit risk created from an economic recession whilst still achieving the policy goal of large-scale lending.

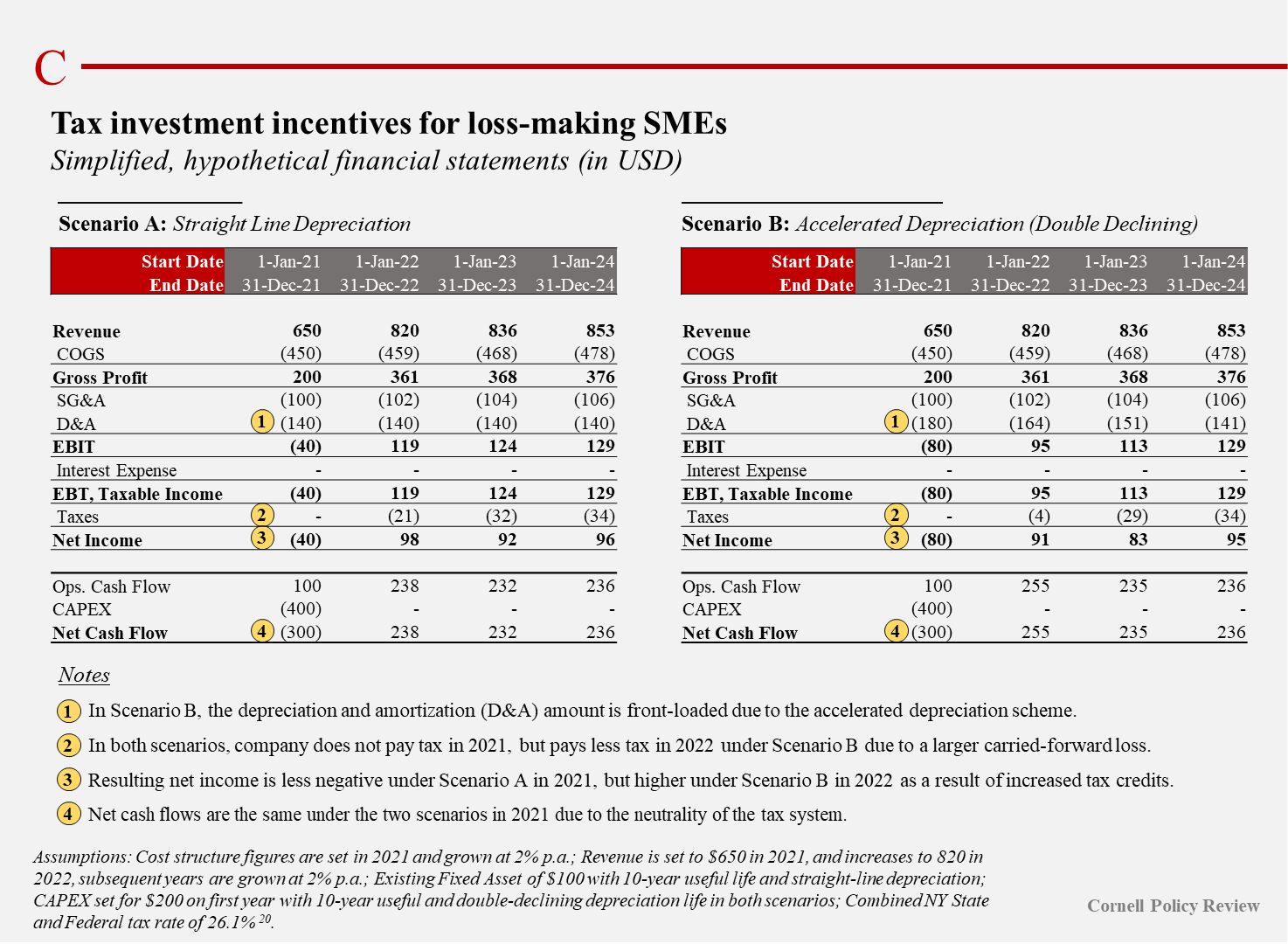

Fiscal measures are another route to incentivize necessary transitionary capital expenditure. Temporary investment tax incentives that expire after a short period will make companies expedite their capital spending to take advantage of potential tax savings given the limited timeframe. Fiscal authorities can develop a list of pre-determined assets for certain industries via their NAICS code that qualifies for a special accelerated depreciation status for tax purposes. Bonus depreciation, as it is also called, allows for more of the capital expenditure to be deducted against this fiscal year’s tax burden – essentially subsidizing investment as cash flow is bolstered.[17]

However, any tax-based policy must consider most companies’ COVID-19-induced loss-making status. Given tax-loss carried forward provisions, an accelerated depreciation regime, as opposed to a standard straight-line method, will benefit a loss-making company only when it becomes profitable in the future. Owing to SMEs’ aforementioned financial constraints with their balance sheet, this investment burden may be too heavy. A supplementary policy catered to loss-making SMEs is a hybrid loss-carry back/forward provision, in which the company can claim a tax refund on prior and future profitable years. [18] This has the potential of achieving two intended policy outcomes: transformative investment spending and granting struggling firms the flexibility to manage their long-term solvency through stronger cash flows. This may cause banks to transition how they view risk from a financial leverage perspective to an interest coverage perspective. Consequently, financial transactions between struggling SMEs and lenders may be evaluated based on the project cash flows – further increasing lending volume as SMEs are no longer constrained by their small balance sheets.[18]

Below are sample income and cash flow statements that demonstrate the impact of an accelerated depreciation schedule for a loss-making company.[19]

Governments must also spur digitization efforts for SMEs’ non-core business functions. This could be a quick win. Initiatives that are on a freemium basis, such as Austria’s Digital Team and Italy’s Digital Solidarity, serve as an aggregator portal of existing providers’ digital services such as access to the internet, teleworking, and cloud computing.[20],[21] These initiatives build business model resilience by building the requisite digital engagement to overcome the hurdles of adoption and by integrating them into the existing digital infrastructure by demonstrably aligning digital tools to their new business model.

Finally, digitization efforts on the asset side must be matched in full force by education and training policies; it would be of little use if there were few competent operators of a company’s technologies. This may create further structural unemployment as low-skill workers are frozen out. Training programs should also encompass managerial skills and corporate governance. Existing commonly-used policies can be further leveraged to tackle this issue. The French government gives a partial wage subsidy to companies that invest in training. Meanwhile, the Chinese government offers SMEs technical and managerial lessons, free of charge, on the existing one-stop-shop SME-catered platform.[22]

Prognosis: Never Let a Good Crisis Go to Waste

Structural policies such as building SME resilience by addressing financing gaps, encouraging digitization, and training workers keep an eye on long-term growth. These policies prepare the economy for a smooth transition to operating at near-total capacity and present the government with an exit strategy to wind down public support and allocate resources to new productive post-pandemic structures.[23] Given the rapid development and deployment of vaccines, most governments will perhaps find neither the time nor the impetus to implement these changes. This may slow down the recovery and exacerbate existing inequalities. More ominously, the lack of enacting structural reforms may leave the economy susceptible and more vulnerable to more severe disruptions such as a more transmissive and deadly (strain of the) virus. Governments keen on increased economic resilience should not let this crisis go to waste, especially as it could mean more remedial measures and spending in the future.

- 2021. http://secure.alacra.com.proxy.library.cornell.edu/. ↑

- Simon, Ruth. “COVID-19 Shuttered More Than 1 Million Small Businesses. Here Is How Five Survived.” The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, August 1, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/covid-19-shuttered-more-than-1-million-small-businesses-here-is-how-five-survived-11596254424. ↑

- “OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019.” OECD. OECD, 2019. https://www.oecd.org/industry/smes/SME-Outlook-Highlights-FINAL.pdf. ↑

- Guellec, Dominique, and Caroline Paunov. “Digital Innovation and the Distribution of Income.” NBER Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research, November 2017. http://pinguet.free.fr/nber23987.pdf. ↑

- Office, U.S. Government Accountability. “Small Business Administration: COVID-19 Loans Lack Controls and Are Susceptible to Fraud.” U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), October 1, 2020. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-21-117T. ↑

- Autor, David, David Cho, Leland Crane, Mita Goldar, Bryan Lutz, Joshua Montes, Ahu Yildirmaz, Daniel Villar, David Ratner, and William B. Peterman. http://economics.mit.edu/files/20094#:~:text=In%20response%20to%20the%20unfolding,2020%2C%20which%20established%20the%20PPP.&text=PPP%20loans%20are%20designed%20to,similar%20to%20pre%2Dcrisis%20levels. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, July 22, 2020. http://economics.mit.edu/files/20094#:~:text=In%20response%20to%20the%20unfolding,2020%2C%20which%20established%20the%20PPP.&text=PPP%20loans%20are%20designed%20to,similar%20to%20pre%2Dcrisis%20levels ↑

- Hubbard, Glenn, and Michael R. Strain. “Has the Paycheck Protection Program Succeeded?” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Brookings Institution, September 24, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Hubbard-Strain-et-al-conference-draft.pdf. ↑

- “Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Loan Calculator.” SBA.com. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.sba.com/funding-a-business/government-small-business-loans/ppp/loan-calculator/. ↑

- O’Mahony, John, and Sara Ma. “Connecting Small Businesses in the US, Commissioned by Google.” https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/technology-media-telecommunications/us-tmt-connected-small-businesses-Jan2018.pdf. Deloitte LLP, 2018. ↑

- Lee, Lisa, and Tom Contiliano. America’s Zombie Companies Rack Up $2 Trillion of Debt. Bloomberg, November 17, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-11-17/america-s-zombie-companies-have-racked-up-1-4-trillion-of-debt#:~:text=Almost%20a%20quarter%20of%20the,laid%20waste%20to%20balance%20sheets. ↑

- “Cash Is King: Flows, Balances, and Buffer Days Evidence from 600,000 Small Businesses.” https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmc/jpmorgan-chase-and-co/institute/pdf/jpmc-institute-small-business-report.pdf. JP Morgan Chase & Co Institute, September 2016. ↑

- “Number of Bank Branches for United States.” FRED. Federal Reserve Economic Data, October 21, 2019. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DDAI02USA643NWDB. ↑

- COVID-19 Government Financing Support Programmes for Businesses. OECD, 2020. https://www.oecd.org/finance/covid-19-Government-Financing-Support-Programmes-for-Businesses.pdf. ↑

- Pearce, Douglas, and Sarah Fathallah. “Rethinking SME Finance Policy – Harnessing Technology and Innovation.” World Bank Blogs. World Bank, March 14, 2014. https://blogs.worldbank.org/psd/rethinking-sme-finance-policy-harnessing-technology-and-innovation. ↑

- Adian, Ikmal, Djeneba Doumbia, Neil Gregory, Alexandros Ragoussis, Aarti Reddy, and Jonathan Timmis. “Small and Medium Enterprises in the Pandemic: Impact, Responses and the Role of Development Finance.” Policy Research Working Papers. World Bank, September 2020. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/729451600968236270/pdf/Small-and-Medium-Enterprises-in-the-Pandemic-Impact-Responses-and-the-Role-of-Development-Finance.pdf. ↑

- Martin, Maximilian. “Understanding the True Potential of Hybrid Financing Strategies for Social Entrepreneurs.” Impact Economy Working Papers. Impact Economy, February 1, 2013. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2209745. ↑

- Wen, Jean-Francois. “Temporary Investment Incentives – International Monetary Fund.” Fiscal Affairs. International Monetary Fund, May 11, 2020. https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/covid19-special-notes/en-special-series-on-covid-19-temporary-investment-incentives.ashx. ↑

- Lean, Jonathan, and Jonathan Tucker. “Information Asymmetry, Small Firm Finance and the Role of Government.” Journal of Finance and Management in Public Services, 2001. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228786557_Information_Asymmetry_Small_Firm_Finance_and_the_Role_of_Government. ↑

- The Center Square. “New York Posts a Combined Corporate Tax Rate of 26.1%.” The Center Square, March 26, 2020. https://www.thecentersquare.com/new_york/new-york-posts-a-combined-corporate-tax-rate-of-26-1/article_22325a84-6927-11ea-90a1-270d7467fdea.html. ↑

- “Digital Team Austria to Support SMEs.” Observatory of Public Sector Innovation, May 7, 2020. https://oecd-opsi.org/covid-response/digital-team-austria-to-support-smes/. ↑

- Sagar, Mohit, Samaya Dharmaraj, and Alita Sharon. “Italy’s Government Set up Digital Solidarity Site to Help Citizens amid COVID-19 Lockdown.” OpenGov Asia, March 12, 2020. https://opengovasia.com/italys-government-set-up-digital-solidarity-site-to-help-citizens-amid-covid-19-lockdown/. ↑

- “Coronavirus (COVID-19): SME Policy Responses.” OECD. OECD, July 15, 2020. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=119_119680-di6h3qgi4x&title=COVID-19_SME_Policy_Responses. ↑

- “Countries Can Take Steps Now to Rebuild from COVID-19.” World Bank, June 2, 2020. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/06/02/countries-can-take-steps-now-to-speed-recovery-from-covid-19. ↑