By: Stephen Shiwei Wang

Edited By: Alejandro Ramos

Introduction

Home insurance prices increased by 11.3 percent in 2023,1 averaging $2,601 annually.2 Bloomberg News reported that the inflation index is projected to rise further should home insurance costs be included.3 For decades, insurance companies have operated on a model based on statistically feasible pricing. With climate change and a milder perception of its ramifications, the recent surge in insurance policy premiums may appear excessively rapid to bear. The challenge arises from the fact that a model that has always worked is no longer functioning as intended, considering the rapid climate change. While both climate change and corporate responsibilities are significant factors, an additional administrative problem is that insurers are hesitant to amend the existing pricing structure, primarily due to the absence of an alternative method to pool economically feasible and risk-responsive policies.

To deal with out-of-control home insurance prices and a mass exodus of insurance companies in high-risk states, policymakers are trying to put a price ceiling on insurance policies. Ceteris paribus, homeowners can take the extra consumer surplus. In practice, however, capping policy premiums tends to reduce insurers’ motivations to offer the policy in the first place––that’s why there are higher home insurance rates, and there are even fewer to offer those policies, reducing home insurance accessibility. What can policies do to help Americans? In this article, I’m exploring alternative public financing routes to give homeowners and insurers a break in the tug-of-war from climate change. My proposition is that a policy can lead to socially optimal insurance by combining grants with subsidies. The problem to explore is who to subsidize and who to give the grants to. Ultimately, this proposal aims to accomplish the following objectives: 1) to enhance community resilience in response to severe weather brought by climate change; 2) to encourage and provide incentives for insurers to develop new pricing models instead of simply exiting risky states; and finally, 3) to implement a combination of premium subsidies and grants to facilitate the transition of objectives 1) and 2).

Climate Change and High-Risk States

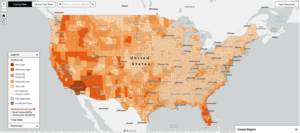

Climate change brings extreme weather events. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) compiled a map to showcase the National Risk Index for states and counties prone to newly developed natural disasters.4 The map contains eighteen climate risks and expected annual loss, social vulnerability, and community resilience by county. Picking attributes such as “drought,” “flooding,” “hurricane,” and “wildfire” as map attributes, it is significant to see some counties and states are unanimously at risk, as shown in Appendix A. The pattern is that coastal states have a higher expected annual loss.5

No One’s Fault

Insurance is fundamentally a negotiation of dilemmas revolving around loss, responsibility, justification, and compensation.6 Before proceeding to the pricing models and alternative funding schedules, it is worth noting that rising insurance premiums adversely impact homeowners and insurers; this is no one’s fault. Think of the home insurance market through the lens of supply and demand: policies are purchased only when consumers’ willingness to pay meets or exceeds suppliers’ willingness to produce. The variable influencing market equilibrium is the expected loss resulting from the accelerated pace of climate change. As prices rise, sellers are more willing to offer policies at a cost, but the actuarial volumes of transactions will decrease. This affects homeowners looking for a policy and insurance companies striving to optimize profits based on previously elevated prices. Ultimately, the basics are still that insurers want to provide insurance products for consumer purchase, while homeowners seek to hedge their risk exposures.

How Do Insurers Operate?

Home insurance policies are created based on three ideas: 1) homeowners want to pay little by little over time to avoid paying a hefty sum for a catastrophe; 2) these devastating events are probable; and 3) some homeowners have high chances to fall victim to these devastating events, some have low risks. Therefore, insurance companies come in and offer policies that allow homeowners to pay little over time to avoid devastating amounts. Of course, the little payment over time must be smaller than the potential lump sum. Otherwise, risks remain uncovered. At this point, homeowners would rather take the risk where there are still chances for no loss, whereas the policy guarantees a payment.

When insurers feel their risks are high, they demand higher regular payments from their clients to hedge the larger risks. If a fire rebuild costs the homeowner $100, and the insurance policy asks for $10 per month over half a year, then the premium-claim spread is $40, where the homeowner pays the insurer $60 in total but avoids a $100 rebuild cost. When a fire happens, the insurer gives $100 to the homeowner, so they save $40; when the fire doesn’t happen, the insurer profits $60 from the homeowner, and everyone is happy because there are no accidents. The spread is a simplified idea representing how much the insurer gains, dictated by the probability of fire. For home insurance in the context of climate change, when the insurer perceives the house is at a dangerous location, they would want clients to pay more so that the insurance can lose less in extreme weather.

The entire insurance market is purely a demand-and-supply transaction. As long as someone is willing to purchase at a particular price, the price is not considered to be “overpriced” in theory because the transaction happens if and only if the buyer is willing to pay for the compensation service—as long as the price is being paid, it’s always fair.

What is the US home insurance providers’ current pricing model?

Insurance companies are risk-based and use statistics models to calculate the expected values of a given client based on traits disclosed and observed. Non-life insurance pricing has three risk factors: 1) properties of the policyholder, 2) properties of the insured objects, and 3) properties of the geographic region. Insurance companies use Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) extensively to deal with probabilities with categorical assumptions to describe data distributions for the group to be insured. At the end of the day:

Premium=Claim Frequency × Claim Severity 7

Since home premiums vary greatly each year, home insurance uses dynamic pricing. For dynamic pricing regulation and welfare, Aizawa and Ko believe that stricter pricing regulation has a limited impact on improving consumer welfare, reducing insurer profits, and increasing market concentration.8

As to how higher insurance prices “permeate” to low-risk regions, it is a process whereby insurers are attempting to redistribute risks from high-risk states to the incomes of low-risk states internally. This practice exacerbates the systemic influences on the variable of climate change and may seem inequitable to the majority of homeowners. Consequently, policy interventions are imperative to mitigate systemic risks and enhance fairness.

Alternative Financing

Grants and subsidies are the two biggest strategies for the home insurance market. There are many tools the government can explore to mitigate price increases. Since price capping (price ceiling) decreases accessibility, as demonstrated in the Introduction, would universal coverage lower the prices as it succeeded in the health insurance industry?

The answer is no. Universal coverage does not extend to home insurance. The distinction lies in whether the traits are observable. In the case of health insurance, high- and low-risk types are unobservable, so this is a situation characterized by “invisible traits”.9 When insurers are unable to identify high-risk individuals, universal coverage integrates everyone, thereby simplifying the insurers’ probability-based calculations. Conversely, home locations are the first accurate information for insurers under climate change. By correlating this readily available property location with natural disaster risk maps that illustrate extreme climate histories, insurers can observe the high-risk groups that are likely victims of climate change. While universal coverage can be adequate when policies also prohibit price discrimination by insurers, it remains a significantly less efficient form of regulation.

First Alternative: Subsidies

Premium subsidies are a method where the government pays a part of the insurance premium to reduce the cost to policyholders.10 This method is commonly used in agriculture industries where high- and low-risk types, like home locations, are also observable across farms and types of crops. Subsidies significantly increase social welfare by increasing consumer and producer surplus through increasing equilibrium transaction quantities, lowering consumer prices, and maintaining producers’ revenues at larger quantities.

Policyholders pay a lower monthly premium for home insurance, but insurers maintain their high prices. Actuarially, more homes are insured in risky states. While this is a great short-term solution, the burdens are solely placed on government subsidies. Thus, the government becomes a social risk redistributor, not the insurance companies. The most apparent downside of a premium subsidy is that the government pays insurers to keep offering their policies at their own pricing pace. This means insurance companies have no stimulus and incentives to adapt and evolve new pricing models.

Second Alternative: Grants

According to FEMA, grants are usually lump sums with a specific purpose, such as supporting “critical recovery initiatives” pre- or post-emergency disasters.11 Grants are government-funded projects that assist states after extreme weather events. For example, FEMA has six types of grants, ranging from extreme weather preparedness to hazard mitigation. In July and August 2024, Governor Kathy Hochul extended the application deadline for emergency repair grants for the state of New York. According to her public comments, “extreme weather events have become all too common in our state.”12 With the absence of universal coverage requirements in home insurance, many homeowners choose, or are unable to, cover their home with a policy. This means many have already been relying on grants in case of extreme weather for repair.

In a sense, grants function as a substitute for insurance policies. An interesting behavior of substitute goods is as the quantity of substitute goods increases, the price of another good decreases. Consider grants as a substitute for homeowner’s insurance. An increase in the availability of grants for homeowners affected by extreme weather would lead to a diminished demand for climate change-related home insurance policies, resulting in lower policy premiums. However, grants are funds that spread “lousiness”: 1) grants don’t incentivize insurance companies to return to risky states they’ve withdrawn; 2) climate emergency grants are typically restrictive in their designated usage. An increase in grants suppresses insurance prices in the weather damage policies but may still cause a further price increase in other insured areas, such as theft; 3) homeowner grants do not promote additional resiliency measures from homeowners. This way, homeowner grants may become an ineffective and myopic solution for hiking home insurance prices and changing climates.

Recommendations

If grants to homeowners cannot provide incentives for resilience-building, then grants directed toward insurers may prove effective. Grant-based insurance companies can become impact insurers by strategically using state or federal funds to improve coverage in high-risk areas, as the grant specifies. According to Nathan Maggiotto, grant-based insurance companies are motivated to employ specifically purposed grants to foster climate change resilience within their coverage offerings.13 This approach fulfills the grant’s intent and positively responds to climate change challenges. This grant-based insurance plan aims to motivate insurers to create innovative models to cope with climate change.

Subsidies should combine grants to insurers and reward positive behaviors that build extreme weather resilience. Instead of subsidizing the price takers, governments compensate for home reinforcements, such as solar panels, for self-sustenance electricity. In addition, the government should provide monetary support for hazardous areas to incentivize emigration to safer places. When subsidies to homeowners match the direction of grants to insurers, the result is more resilient houses with affordable and available insurance policies.

If unreasonable home insurance premiums are the symptom, finding alternative financing to lower the price is only temporary. In the face of extreme weather caused by accelerated climate change, houses and insurance models both need a quick update to meet the latest challenges. The root of this symptom is a lack of home resilience and insurers’ incentive to evolve. With policies geared toward building long-term resilience, the subsidy-grant hybrid model can become the key to the solution.

Appendix: FEMA Map of Expected Annual Losses by States

Figure 2: Drought Expected Loss

Figure 3: Riverine Flooding Expected Loss

Figure 4: Hurricane Expected Loss

Figure 4: Hurricane Expected Loss

Figure 5: Wildfire Expected Loss

Figure 5: Wildfire Expected Loss

Works Cited

1. Duvall, Mel, Brent Buell, & Leslie Kasperowicz. 2024. “Home Insurance Rate Increases: Top Companies’ Rates Increased 11.3% on Average in 2023.” Insurance.com. August 16. https://www.insurance.com/home-and-renters-insurance/home-insurance-rate-increases

2. Kasperowicz, Leslie, Brent Buell, & John McCormick. 2024. “Average Homeowners Insurance Rates by State in 2024.” Insurance.com. November 28. https://www.insurance.com/home-and-renters-insurance/home-insurance-basics/average-homeowners-insurance-rates-by-state#zip-tool

3. Zahra Hirji; Bloomberg News. 2024. “If US Inflation Reflected Rising Home Insurance Costs, It’d Be Even Higher.” Lincoln Journal Star (NE), April 16. https://research-ebsco-com.proxy.library.cornell.edu/linkprocessor/plink?id=56a98f2f-7cf5-3dcc-8e03-15a35c48e6b2

4. FEMA. 2023. “Map | National Risk Index.” 2023. https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/map

5. Ibid.

6. Knight, Amy, Stéphanie Barral, Max Besbris, and Caleb Scoville. 2023. “On Rebecca Elliott’s Underwater: Loss, Flood Insurance, and the Moral Economy of Climate Change in the United States, Columbia University Press, 2021.” Socio-Economic Review 21 (3): 1823–33. www.doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwad017

7. Ohlsson, E., & Johansson, B. (2010). Non-Life Insurance Pricing with Generalized Linear Models. 1st ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. https://resolver.ebscohost.com/Redirect/PRL?EPPackageLocationID=1510.649642.0&epcustomerid=s9001366

8. Aizawa, Naoki, & Ami Ko. 2023. Dynamic Pricing Regulation and Welfare in Insurance Markets. Cambridge, Mass: National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w30952

9. Gruber, Jonathan. 2016. Public finance and public policy. Fifth edition. New York: Worth Publishers.

10. Michels, Marius, Hendrik Wever, and Oliver Mußhoff. 2024. “Cultivating Support: An Ex-Ante Typological Analysis of Farmers’ Responses to Multi-Peril Crop Insurance Subsidies.” Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics 56 (2): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/aae.2024.8

11. FEMA. 2023. “Grants | FEMA.gov.”

12. “United States: Governor Hochul Extends Application Deadline for Income Eligible Homeowners to Apply for Emergency Repair Grants for July and August Extreme Weather Events.” TendersInfo News, October 22. NA. . https://link-gale-com.proxy.library.cornell.edu/apps/doc/A813222788/STND?u=cornell&sid=ebsco&xid=a9ed05d8

13. Maggiotto, Nathan. 2024. “You’re Not Covered: Insurance in a Climate Constrained World”. Speech presented at Cornell Energy Connection 2024, Roosevelt Island, NY, November 22 at 1:45 pm ET.