Nearly 125 million people around the world depend on coffee for their livelihoods (Research for Nourish Africa IITA; Fair Trade and Coffee, 2012). When we think of major coffee producers, we might think of Brazil, Colombia, or Ethiopia, but since 2000 Vietnam has become the world’s second largest coffee exporter, exporting a total of 17.6 million 60 kg bags in 2007 and 25 million 60 kg bags in 2015 (Vietnam Coffee Annual-Gain Report 2007, 2015). From 1992 to the present, the world’s coffee output rose by 23% as Vietnam emerged as a major producer, following a deliberate, publicly-supported move into the sector with a focus on cultivating Robusta beans (Africa Centre for Economic Transformation, 2014). Correspondingly, coffee production in Vietnam has experienced significant growth per year. Between 1980 and 2000, Vietnam went from producing 8,400 tons of coffee to producing 900,000 tons, averaging more than 26 percent growth per year. Half a million small-scale coffee farmers now grow beans by cultivating two to three acres of land.

In the last decade of the twentieth century, Vietnam’s GDP increased at an average of 7.7%, with coffee an important contributor to the country’s overall economic expansion (Africa Centre for Economic Transformation, 2014). Further, as BBC News reported on 25 January 2014, the significant growth in coffee production has enabled a large number of Vietnamese farmers to make a living from coffee; while in 1994 some 60% of the Vietnamese population lived below the poverty line, now less than 10% do. Small-scale coffee-growing farmers, for whom coffee is their main source of income, comprise the majority of coffee-growing households in Vietnam. These households have long struggled with issues surrounding coffee production and exportation for global commodity markets. While exporting coffee can potentially provide farmers the opportunity to improve their livelihoods, households have to respond assertively to increasing competitions in the international environment in various aspects. However, as Vietnam’s key export, the Vietnamese coffee industry has no globally-known self brands such as the 100% Colombian Coffee or coffee chains, which has prevented it from accessing substantial premiums and reaping wider profit margins in the global market.

Comparing coffee sector development in Vietnam and Colombia

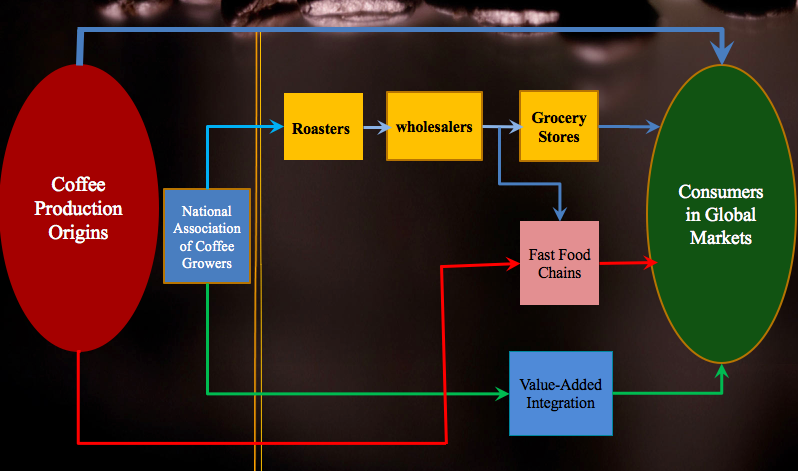

Figure 1: Simplified coffee supply chain in Columbia and Vietnam

While the coffee industries of Vietnam and Colombia have several factors in common, each of these major coffee exporters has its own mechanisms. Their fundamental supply chains—by which beans grown by households become a cup of coffee consumed by customers—is similar, shown in Figure 1. Furthermore, the two countries do not consume much of their own produced coffee, and coffee drinking has not been a traditional preference of their people. Thirdly, both countries have implemented diverse strategies in order to compete for global markets through coffee product differentiation.

Figure 1 shows a simplified global supply chain for Café de Colombia and coffee in Vietnam. The supply chain usually comprises coffee bean production, processing, marketing, distribution, and consumption. Coffee growers in Colombia mainly sell their harvest to growers’ cooperatives, and also MNCs and domestic coffee exporting firms. However, the Vietnamese coffee sector positions itself as a manufacturer in the global value chain of coffee, holding the belief that they do not have the capacity to enter the global coffee market with its own brand. Under such circumstances, the interaction between consumers and Vietnam’s coffee producers is fairly week. This results in requiring a different marketing process of Vietnam coffee in terms of the global supply chain.

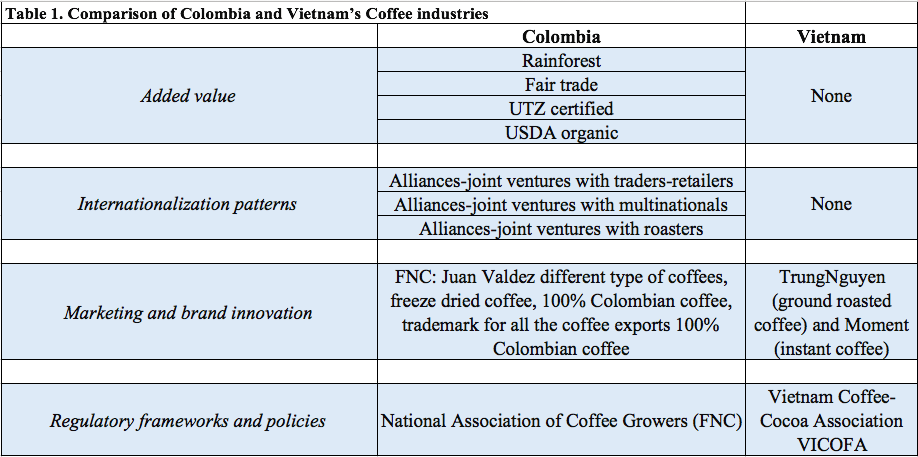

The similarities and differences at work in these coffee-producing countries are yet more extensive. First of all, the coffees’ origins and destinations are different: Colombia mainly produces Arabica coffee beans, while Vietnam produces 90% of the Robusta products; consumers of the former are mainly based in the US, while consumers of the latter are primarily in Europe. In 2012, UNCTAD sponsored a cross-country study that specifically compared Colombia and Vietnam in terms of their coffee, cooperation and competition. Unlike the general supply chain shown in Figure 1, Table 1 presents extracted items that demonstrate the major differences between the two coffee markets in terms of value adding, internationalization patterns, marketing and brand innovation, and regulatory frameworks and policies.

Source: Gonzalez-Perez et al., 2012

Except for the fact that the Colombian coffee sector has experienced the whole process of its own coffee brand building and acknowledgement over the past couple of decades, Colombian government further developed favored policies and programs to offset small-scale producers. Apparently, the coffee industry in Vietnam has yet to explore the brand building and public private partnerships in establishing a national brand. Hence, what lessons could Vietnam learn from the Columbia coffee sector’s past? What future development strategies can be informed by the context of Colombia?

Future development strategies for Vietnamese coffee industry

Due to the increasing competition of the coffee market, and thus the coffee price is rather volatile. Facing the impact that coffee price volatility has on Vietnamese coffee growers in the context of the increasing competition, Vietnam coffee sector needs a better path out to help mitigate coffee farmers’ risks. Informed by the story of Colombian coffee, integration into the international coffee community is not only a way out of Vietnamese coffee’s present dilemma; it is also a way of adding value to Vietnam’s current coffee sector. Here are some alternative solutions.

To establish alliance-joint ventures

Referring to one of the driving forces behind Colombia’s coffee success, the first step for the development of the Vietnamese coffee sector should be to establish alliance-joint ventures. These ventures would allow Vietnamese coffee to gain an entrance ticket in either multinational specialty chains, such as Starbucks, or major retailers and roasters, such as Kraft and Nestle. Luckily, Vietnamese coffee has already started to make progress on this front. According to VOVNEW on September 25, 2015, Starbucks has announced that it will sell Vietnamese coffee at more than 21,500 of its shops in 56 countries. Aside from alliance-joint ventures with traders-retailers to enter the multinational specialty train, alliances also exist in joint ventures with traders and roasters.

To acquire national and international certifications

Certifications such as USDA organic certifications and Fair trade certification mark shall ensure profitability and buffer the volatility of coffee prices. Colombian coffee benefited from registering the term 100% Colombian Coffee as a trade mark. Fairtrade mark, to serve as another example, is best known for ensuring that farmers earn enough to cover at least the basic costs of sustainable production, even against a fallen coffee price. To get other certifications imply similar purposes. Of course, in order to be certified, producers have to comply with certain standards such as the Fairtrade Standards.

The third strategy is to expand its business in new markets

Given the increasing demand for coffee in Hong Kong, Mainland China, Japan, Korea, and even Colombia, Vietnam should think about how to expand its coffee business into these regions. Vietnam should make the most of its two most competitive advantages: low cost of labor and transportation; limited government regulation (e.g. no tax for 50 years); and, compared to its rival coffee-producing countries, convenient transportation from grower’s land to regional hub to the Ho Chi Min port for exportation. Also considering expanding business, by blending several kinds of coffee will diversify Vietnam’s coffee offerings, which could divert the risks involved with entering new markets with limited varieties.

Providing value-added services through a vertical integration approach

The Vietnamese market itself actually presents opportunities for growth, because domestic coffee consumption can be an important stimulus to growth. The strategy is to employ traditional marketing strategies to help raising the value of Vietnamese coffee by building Vietnam’s brands and making processed products. Despite producing coffee for export, the Vietnamese population has traditionally drunk tea; future advertising initiatives must consequently encourage altering consumers’ drinking habits, imagining and creating a domestic market rather than tapping a consumer base that already exists. Because Vietnamese coffee production is already primarily for export, how does the domestic market relate to the global marketing of the coffee is not going to be easy. To compete with the big players internationally, creating Vietnamese coffee culture is one way to start bringing Vietnam’s coffee to the world.

Whatever strategy (or combination of strategies) is embarked upon, the role of public policies will be to secure a sound future for the Vietnam coffee industry. Achieving sustainable growth requires effective action from multiple parties, and government, private sectors and all stakeholders in the coffee value chain should all be in place. The lessons of Colombia’s coffee successes should guide Vietnam’s public policy priorities.

Policy recommendations

Establishing a cooperation mechanism

Vietnam should establish a cooperation mechanism between coffee intermediaries and coffee producers, especially individual farmers. In Vietnam, VICOFA is currently an association representing only coffee exporters—not coffee producers. This lack of representation contributes to farmers’ vulnerability of farmers when faced with external changes in the world coffee market. The operation of the National Federation of Coffee Growers in Colombia, with different representative layers from the grassroots up to the national level, can be an example to Vietnam.

Raising the awareness of coffee producers: Learning, training, and capacity-building

Establishing cooperation mechanisms will foster relationships among government and local representatives, which will likely work together in raising awareness of capacity building for coffee farmers and other value chain actors. Enhancing producers’ capacity for market integration will significantly influence the coffee processing amongst small-scale farmers.

Moreover, cooperation mechanisms are also expected to provide instant market information and applications of technology advancement to farmers. Presently, a large number of small-scale farmers in Vietnam lack an adequate understanding of the effects of the advancing coffee value chain; coffee farmers are still using antiquated methods to process beans, in a way that cannot sufficiently ensure the efficiency, security and quality of their products. International businesspeople have recently taken notice of this situation, as, for example, Nestle has undertaken to help Vietnam cultivate its coffee industry.

Setting up financial instruments for modern agricultural inputs

Another challenge small-scale farmers face when trying to increase their productivity is acquiring the capital to buy modern agricultural inputs. Hence, there is another mission of the cooperation mechanisms: to work with farmers and to set up financial instruments, such as co-ops and loaning circles, which can help farmers build up the capital they need to invest in their farms without exposing them to horrendous financial risks. If Vietnam’s farmers are able to upgrade their farm infrastructure in ways that bring in cooling and other processing facilities, farmers will be able to produce higher-quality coffee given that Vietnam has the environment for planting high quality coffee. New market segment is accessible then backed up by financial instrumentation.

Public-private partnerships building up more know-how and farming management systems

Public-private initiatives should encourage small-scale farmers to attend certification programs that aim to improve both the quality of coffee growing and farmers’ compliance with international regulations and quality standards. Partnerships are necessary for working together to develop or jointly establish research institutes to prevent crops from damage by herbicides pesticides and improved seeds. For instance, the Cenicafe of FNC in Colombia has been focusing on research and development on methods to increase coffee yields and quality. Vietnam can have such organizations and learn from that as well.

All in all, it has been proved in Colombia that public-private cooperation works to increase farmers’ access to capacity building and training. Hence, it is time for Vietnamese governments, coffee research institutes, VICOFA, international and local exporters, and NGOs to unite their efforts, share their knowledge and work together to bring their coffee brand at a global level. This will be the only way to scale up the production of sustainably produced coffee and secure the future of the sector.” The prosperity of Vietnamese coffee industry is yet to come.

References

Gonzalez-Perez, Maria-Alejandra, and Santiago Gutierrez-Viana. “Cooperation in coffee markets: the case of Vietnam and Colombia.” Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies 2, no. 1 (2012): 57-73.