Written by: Jason Hung

Edited by: Adam Terragnoli

Introduction

Academics and journalists have referred to the prison system in England and Wales a “prison crisis”.[1] [2] The term prison crisis refers to core managerial and operational problems in prison settings, including overcrowding, staff shortages, housing difficulties and incidents of self-harm.[3] The overcrowded and poorly managed prisons have caused tension in the prison population, leading to housing and social issues.[4] Such challenges foster interpersonal conflicts which result in psychosocial suffering among prisoners.

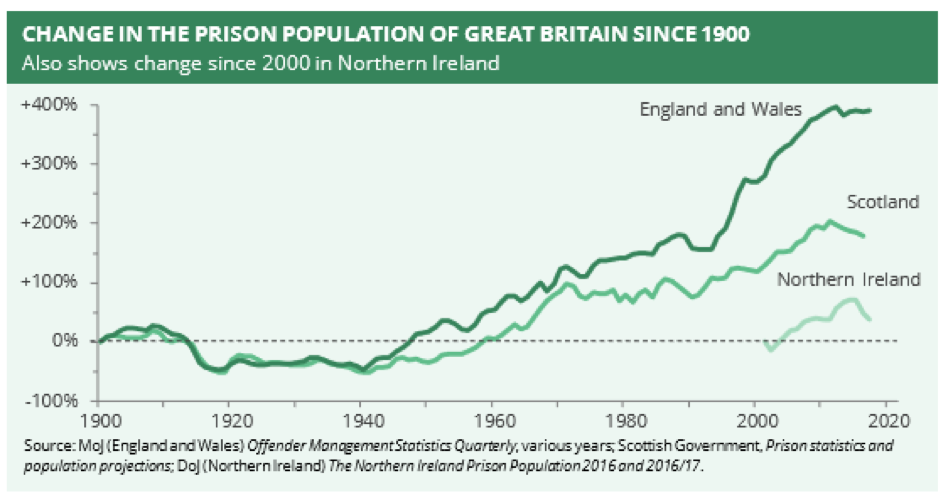

The prison population in England and Wales has increased continually and has since ballooned from approximately 20,000 in 1950 to 85,843 prisoners, the highest prison population in Europe (see TABLE 1). [5] [6] The continual growth of the prison population in England and Wales has increased housing and financial pressure on prison services, yet substantial funding cuts have compounded such pressure and have jeopardized the personal safety and psychosocial wellbeing of those incarcerated.[7]

Table 1: Prison Population in Europe

The failure of imprisonment systems

According to Section 142 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003, prison is a setting used to punish offenders and reduce crime rates through incapacitation (the removal of individuals from the society against which they are deemed to have offended.), deterrence, retribution and rehabilitation.[8] The British Government is legally responsible for the punishment of those who harm others physically, mentally, financially or otherwise.[9] [10] [11] However, according to prison scholars (e.g. Professor Keith Hawton, Dr. Sandra L. Resodihardjo, Dr. Lisa Marzano) and inspectors (from Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons for England and Wales), any punishment needs to be exercised with humanity and for an intended good.[12] [13] When imprisonment proves inhumane and poor conditions lead to interpersonal strife, violence and self-harm, these professionals denounce prisoners, arguing that they are immoral, demeaning and damaging to those confined within their walls.[14] [15]

Overcrowding and psychosocial wellbeing

Prison overcrowding results in the lack of private space, which increases social conflicts about noise, smell and the proximity of neighbors.[16] [17] [18] The interpersonal friction exacerbates physical and psychosocial problems of prisoners, prompting cases of self harm and suicide.[19] According to the Ministry of Justice, the assault incident rates grew from 160 per 1,000 prisoners between April 2003 and March 2004, to 260 assaults per 1,000 prisoners between April 2015 and March 2016.[20] Simultaneously, there was a substantial rise in incidents of self-harm, from approximately 18,000 cases between April 2003 and March 2004, to 35,000 cases between April 2015 and March 2016.[21] A total of 317 deaths occurred in prisons between March 20, 2017 and March 19, 2018. [22]

The Prison and Probation Ombudsman (PPO) found that 22 percent (79 out of 358 individuals) of those who died in prison from fatal suicide suffered from mental disorders, in addition to 70 percent (139 out of 199 individuals) of those died from self-inflicted injuries suffered from psychological challenges.[23] Such figures suggest that mental health conditions are a leading cause of self-inflicted deaths in prison in England and Wales. These statistics demonstrated that the physical and psychosocial wellbeing of prisoners have been compromised by poor conditions, thereby confirming the reality of the prison crisis.

Furthermore, the prison population doubled from 1993 to 2018.[24] However, funding for correctional services in the UK has been cut by 20 percent since 2009. A total of £900 million funding decrease has often been blamed for the prison crisis.[25] Prison facilities are inadequate due to overcrowding and underfunding issues.[26] Prisoners moreover face reduced opportunities to participate in out-of-cell activities, a situation which negatively impacts upon psychosocial wellbeing.[27] [28]

Medical staffing shortages

A shortage of healthcare workers also contributes to poor mental health and wellbeing among prisoners, who will often go untreated. In 2014, the then Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice Chris Grayling argued that an unmet demand for staff was harming prison populations.[29] [30] For example, between 2010 and 2013, the number of frontline prison officers in England and Wales dropped by 30 percent, from 27,650 to 19,325. Here prisoners officers in frontline roles are band three to five staff, which are the key operational grades in public prisons and consist of officers, specialists, supervising officers and custodial managers. Most prison officers were forced to operate with 40 percent fewer staff than before. Additionally, 18 prisons were closed or re-rolled as immigration removal centres (IRCs), resulting in a loss of almost 6,500 units of prison capacity. As a result, prisoners were less likely to be allowed to participate in, the right to rehabilitative and leisure activities were decreased or denied due to understaffing. Prisoners were also forced to spend more time locked up in their cells.[31]

According to Social Protection & Human Rights (SPHR), shortages in medical staffing may violate Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which states that each prisoner is entitled to the “highest attainment standard” of health, both physically and mentally.[32] [33] SPHR is a collaboration between the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) and the former United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, Magdalena Sepúlveda to enhance the awareness of implementing, and develop the capacity to implement, a human rights-based approach to social protection.[34] Shortage of medical staffing in prison is not legally or morally justifiable to punish prisoners with poor living conditions that may negatively impact on their physical and psychological health.[35] [36] Prisoners’ psychosocial wellbeing, harmed by imprisonment, must be maximized, insofar as they are entitled to well-facilitated medical support. The HM Prison and Probation Service asserts that helping offenders recover from illness, mentally or otherwise, could deter re-offence.[37]

According to Section 41 and 42 of the European Prison Rules, and Rule 25 of the Standard Minimum Rules, at least one qualified general medical professional should be on duty in each prison to take care of both the physical and mental health of prisoners on a daily basis.[38] [39] [40] However, according to Jane Senior et al., only 25 percent of prisoners with severe mental impairments were examined by in-reach services. Additionally, only 13 percent of prisoners received medical treatment.[41] Prisoners who experience severe mental health crisis are placed on bed watch (monitoring inmates in hospital) where there is an absence of specialists to provide therapeutic and clinical support in most circumstances.[42] For those who are psychosocially vulnerable, the need for medical intervention is often understood to signal discipline and self-control problems. That is, illness is treated as a behavioral, rather than medical, issue. This leads to the segregation of prisoners, but not the provision of care they need.[43] In segregation units, Sharon Shalev and Kimmett Edgar found that nurses visited prisoners cell by cell on a daily basis.[44] However, conversations were likely to be overheard due to the lack of privacy and confidentiality created by the presence of inmates. As a consequence, many prisoners were reluctant to discuss their psychosocial wellbeing in detail.[45]

[46] [47] In addition to the lack of proper medical consultations, lower staff levels make it more difficult to, among other things, prevent illegal substances from entering prisons, including psychoactive substances.[48] Furthermore, staff shortages prevent the identification of substance abuse, impeding the efficiency of early intervention.[49] The annual report by the Chief Inspector of Prisons confirmed that the consumption of illicit substances facilitated serious assaults and violence.[50] As a result, imprisoned individuals experience a greater number of interpersonal conflicts and psychosocial challenges. The presence of illegal substances therefore helps explain the number of reported incidents of self-harm and death in prisons and IRCs.[51] [52] [53]

When the prison population increases and funding for prisoner services decreases, the outcomes are psychosocial harms to prisoners.[54] [55] Although it is the National Health Service (NHS) policy that prisoners with acute mental health problems should not wait over 14 days to be sent to hospitals, the Public Accounts Committee, a body appointed by the House of Commons to hold the government and its civil servants to account for the delivery of public services, reported that two-thirds of the 1,081 mentally disordered prisoners waited more than 14 days to be transferred to hospitals in 2016 and 2017.[56] [57] Moreover, 7 percent waited over 140 days. Many prisoners with acute and severe mental disorders could not receive any NHS in-patient care in a timely manner.[58] Among those who were diagnosed with mental disorders, PPO discovered that one in every five never received any mental health support from medical staff.[59]

Necessary and unnecessary harms

Imprisonment often results in rights violations.[60] [61] These rights violations constitute what has been termed retribution, a form of punishment exceeds the consequences of imprisonment. For example, even if ex-prisoners do not experience overt discrimination, many encounter internalized stigma regarding their criminal records and identities.[62] According to Russell Christopher (2002), internalized stigmatization is the necessary sanction prisoners and ex-prisoners have to suffer as a consequence of their criminality. Any additional suffering as consequences of funding cuts and overcrowding issues in prisons certainly inflict harms on prisoners to a way that exceeds necessary harms.[63]

Shortage of rehabilitative activities

In terms of psychosocial wellbeing, Dora Rickford and Kimmett Edgar reported that prisoners were substantially less psychosocially distressed when they spent less time in cells, and more time in studying, working and recreational activities.[64] While remaining outside of cells for 10 hours a day is regarded as the minimum time span prisoners should be spending outside of cells to maintain their mental wellbeing, surveys from HM Inspectorate of Prisons found that this was only the case for 14 percent of prisoners during 2014-15 and 2015-16.[65] A recent study conducted by Sharon Shalev and Kimmett Edgar argued that as little as 42 percent of prisoners were given opportunities to pursue education on a weekly basis.[66] Regarding prisoners’ satisfaction levels of rehabilitative activities, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales reported that 56 percent of prisoners were dissatisfied with the quality of those activities.[67] NHS Mental Health Trusts surveyed 133 prisoners in England and Wales in 2009 and found that the quality of rehabilitative activities was positively correlated to the mental wellbeing of prisoners.[68] The majority of those satisfied with the quality of rehabilitative services were more likely to be successfully discharged to the community.[69] In prison, when rehabilitative services are poor, prisoners cannot benefit from them, resulting in the deterioration of prisoners’ mental wellbeing.

Conclusion

According to the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice, Elizabeth Truss, HM Prison and Probation Service should receive an increase of governmental funding due to the continual increase in prison population.[70] Additional funding should be used to hire more long-term staff, including medical staff, and build prison facilities.[71] Sufficient staff levels on duty in prisons are necessary to realize early diagnosis of and intervention against psychosocial suffering among prisoners. Intervention policies include providing therapeutic and clinical support to inmates who are in medical needs or requesting for medical care. Also, increasing security staff levels will enable early identification of substance abuse, minimizing interpersonal conflicts – such as assaults and violence – and psychosocial suffering among prisoners. A reduction in negative psychosocial impacts on prisoners can decrease the probability of reoffending. This helps facilitate crime control in England and Wales and, thus, lower the costs of imprisonment in the long-term.

-

Fox, Chris and Albertson, Kevin (2010) “Could Economics Solve the Prison Crisis?”, Probation Journal, 57 (3), 263-80. ↑

-

Resodihardjo, Sandra, Crisis and Change in the British and Dutch Prison Services: Understanding Crisis-Reform Processes (London: Routledge, 2016). ↑

-

Alison Liebling and Amy Ludlow, “Suicide, Distress and the Quality of Prison Life,” in Handbooks on Prisons, ed. Yvonne Jewkes, Jamie Bennett and Ben Crewe (Devon: Willan Publishing, 2016), 226. ↑

-

International Centre for Prison Studies (ICPS), “Dealing with Prison Overcrowding,” Guidance Note 4 (London: King’s College London), 1. ↑

-

“World Prison Population List (11th edition),” Roy Walmsley, (Institute for Criminal Policy Research (ICPR), n.d.), last modified November 2014, www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/world_prison_population_list_11th_edition_0.pdf. ↑

-

Tim NewBurn, “Penology and Punishment,” Criminology (London: Routledge, 2013 [2007]), 713. ↑

-

Andrew Coyle, “Management of Prisoners,” Managing Prisons in a Time of Change (London: International Centre for Prison Studies, 2002), 28. ↑

-

“Criminal Justice Act 2003,” legislation.gov.uk., last modified n.d. www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/44/section/142. ↑

-

“Crime in England and Wales: Year Ending September 2017,” GOV.UK., last modified February 23, 2017, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/crimeinenglandandwales/yearendingseptember2017. ↑

-

Tony Ward and Karen Salmon, “The Ethics of Punishment: Correctional Practice Implications,” Aggression and Violent Behavior 14, no. 4 (2009): 243. ↑

-

Paddy Hillyard and Steve Tombs, “Beyond Criminology?” in Criminal Obsessions: Why Harm Matters More Than Crime, ed. Danny Dorling, Dave Gordon, Paddy Hillyard, Christina Pantazis, Simon Pemberton and Steve Tombs (London: Centre for Crime and Justice Studies, 2008), 15. ↑

-

Ian O’Donnell, “The aims of Imprisonment,” in Handbooks on Prisons, ed. Yvonne Jewkes, Jamie Bennett and Ben Crewe (Devon: Willan Publishing, 2016), 42. ↑

-

Tony Ward and Karen Salmon, 2009, 240. ↑

-

Roger Matthews, “The Future of Imprisonment,” Doing Time: An Introduction to the Sociology of Imprisonment (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 1999), 243. ↑

-

Chris Fox and Kevin Albertson, “Could Economic Solve the Prison Crisis?” Probation Journal 57, no. 3 (2010): 263-80. ↑

-

Dominique Moran, “Prisoner Reintegration and the Stigma of Prison Time Inscribed on the Body,” Punishment and Society 14, no. 5 (2012): 573. ↑

-

Anthony Taylor. “Prison Overcrowding,” Prison System and its Effects: Where from, Where to, and Why? (New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers, 2011), 98. ↑

-

Mona Marshy, “Social and Psychological Effects of Overcrowding in Palestinian Refugee Camps in the West Bank and Gaza,” Literature Review and Preliminary Assessment of the Problem (Ottawa, IL: International Development Research Centre, 1999). ↑

-

Andrew Coyle (2002): 28. ↑

-

“Safety in Custody Statistics Bulletin: Deaths in Prison Custody to June 2016, Assaults and Self-Harm to March 2016,” Ministry of Justice, 10, last modified July 27, 2017, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/543284/safety-in-custody-bulletin.pdf. ↑

-

Ministry of Justice (2017): 9. ↑

-

Safety in Custody Summary Tables to December 2018,” GOV.UK, last modified April 25, 2019, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/safety-in-custody-quarterly-update-to-december-2018. ↑

-

“Learning from PPO Investigations: Prisoner Mental Health,” The Prisons & Probation Ombudsman (PPO), 12, last modified January 2016, http://www.ppo.gov.uk/app/uploads/2016/01/PPO-thematic-prisoners-mental-health-web-final.pdf. ↑

-

“UK Prison Crisis – in Numbers,” The Telegraph, last modified December 19, 2016, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/12/19/uk-prison-crisis-numbers/. ↑

-

“UK Prisons in Crisis: Privatisation, Cuts, and Overcrowding a Recipe for Anarchy,” International Business Times, last modified June 17, 2015 https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/uk-prisons-crisis-privatization-cuts-overcrowding-recipe-anarchy-1506658, ↑

-

Andrew Coyle, A Human Rights Approach to Prison Management Handbook for Prison Staff (London: International Centre for Prison Studies, King’s College London, 2009): 11. ↑

-

Andrew Coyle (2002): 28. ↑

-

Life in Prison: Living Conditions, HM Inspectorate of Prisons, last modified October 2017, https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2017/10/Findings-paper-Living-conditions-FINAL-.pdf. ↑

-

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 11. ↑

-

“UK Parliament Commons Debates,” House of Commons, last modified June 16 2014, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201415/cmhansrd/cm140616/debtext/140616-0001.htm#column_841. ↑

-

“Breaking Point: Understanding and Overcrowding in Prisons, Research Briefing,” The Howard League for Penal Reform (2014) https://howardleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Breaking-point-10.07.2014.pdf ↑

-

“Social Protection Systems and Social Protection Floors,” Social Protection & Human Rights (n.d.) https://socialprotection-humanrights.org/key-issues/social-protection-systems/social-protection-systems-and-social-protection-floors/. ↑

-

Andrew Coyle, “Standards in Prison Health: The Prisoner as a Patient,” in Health in Prisons: A WHO Guide to the Essentials in Prison Health, ed. Lars Moller, Heino Stover, Ralf Jurgens, Alex Gatherer and Haik Nikogosian (Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2007): 7. ↑

-

“History”, Social Protection and Human Rights (SPHR), last modified n.d. https://socialprotection-humanrights.org/about/ ↑

-

Ian O’Donnell (2016): 42. ↑

-

Tony Ward and Karen Salmon (2009): 240. ↑

-

“Healthcare for Offenders,” GOV.UK., last modified December 21, 2018, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/healthcare-for-offenders. ↑

-

Andrew Coyle (2007): 12. ↑

-

Council of Europe, European Prison Rules (Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, 2006): 20. ↑

-

“Human Rights and Prisons: Manual on Human Rights Training for Prison Officials,” Professional Training Series No. 11, Office of The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) (Geneva: United Nations, 2005): 63, 66. ↑

-

Jane Senior, Luke Birmingham, Mari Harty and Lamiece Hassan, “Identification and Management of Prisoners with Severe Psychiatric Illness by Specialist Mental Health Services,” Psychological Medicine 43, no. 7 (2013): 1511-20. ↑

-

“Mental Health in Prisons Environment,” Mental health in prisons: Eighth Report of Session 2017-19, Public Accounts Committee, 13, last modified December 6, 2017, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmpubacc/400/400.pdf. ↑

-

Deborah Coles and Peter Smith, “Death in Custody,” The All-Party Parliamentary Penal Affairs Group (London: Prison Reform Trust, 2008): 25. ↑

-

Sharon Shalev and Kimmett Edgar, “Segregation and CSCs: Conditions, Provisions, Regime and Support,” Segregation Units and Close Supervision Centres in England and Wales (London: Prison Reform Trust, 2015): 58. ↑

-

ibid. ↑

-

Ministry of Justice (2016). ↑

-

Anastasia Chamberien et al., “Is There a Prison Crisis?” Prison Service Journal 243, no. 1 (2019), 2. ↑

-

“UK: Prisons officers protest over staff shortages and safety concerns,” European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound), last modified March 16, 2017 https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/observatories/eurwork/articles/uk-prisons-officers-protest-over-staff-shortages-and-safety-concerns ↑

-

Dora Rickford and Kimmett Edgar, “The Context of Diversion and Liaison Schemes,” Troubled Inside: Responding to the Mental Health Needs of Men in Prisons (London, Prison Reform Trust, 2005): 9. ↑

-

Annual Report 2014-15, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales, last modified July 14, 2015, https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2015/07/HMIP-AR_2014-15_TSO_Final1.pdf. ↑

-

Tony Ward and Karen Salmon (2009): 242. ↑

-

John Hodge and Stanley Renwick, “Motivating Mentally Disordered Offenders,” in Motivating Offenders to Change: A Guide to Enhancing Engagement in Therapy, ed. Mary McMurran (New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons): 229. ↑

-

Richard Sparks, “Prisons, Punishment and Penalty,” in Controlling Crime, ed. Eugene McLaughlin and John Muncie (London: SAGE Publications, 1996): 207. ↑

-

Andrew Coyle (2009): 11. ↑

-

Peter Bennett, “Prisons and Human Rights,” in Handbooks on Prisons, ed. Yvonne Jewkes, Jamie Bennett and Ben Crewe (Devon: Willan Publishing. 2016): 330. ↑

-

“Our Role – Public Accounts Committee”, www.parliament.uk (n.d.) https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/public-accounts-committee/role/ ↑

-

Public Accounts Committee (2017): 13. ↑

-

John Reed. “Mental Health Care in Prisons,” British Journal of Psychiatry 182, no. 4, 287. ↑

-

“Mental health care in prisons.” Prison Reform Trust, last modified, n.d., http://www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/WhatWeDo/ProjectsResearch/Mentalhealth. ↑

-

Andrew Coyle (2009): 11. ↑

-

“Dealing with Prison Overcrowding,” Guidance Note 4, International Centre for Prison Studies (ICPS) (London: King’s College London), 2. ↑

-

Dominique Moran (2012): 568. ↑

-

Russell Christopher (2002): 866. ↑

-

Dora Rickford and Kimmett Edgar, “Self Harm in Custody,” Troubled Inside: Responding to the Mental Health Needs of Men in Prison (London: Prison Reform Trust, 2005): 76. ↑

-

Yarl’s Wood Immigration Removal Centre, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, last modified June 5-16, 2017, 38, https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2017/11/Yarls-Wood-Web-2017.pdf. ↑

-

Sharon Shalev and Kimmett Edgar (2015): 47. ↑

-

Annual Report 2015-16, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales, 17, last modified July 19, 2016, https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/07/HMIP-AR_2015-16_web.pdf. ↑

-

Helen Killaspy, “Mental Health Rehabilitation Services: Why Quality Matters,” last modified April 2015, https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/Mental%20Health%20Rehabilitation%20Services%20Why%20Quality%20Matters.pdf. ↑

-

ibid. ↑

-

“Prison in England and Wales to Get 2,500 Extra Staff to Tackle Violence,” The Guardian, last modified November 3, 2016 https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/nov/02/prisons-in-england-and-wales-given-boost-of-2500-new-staff-to-tackle-violence ↑

-

ibid. ↑