By: Alejandro J. Ramos and Jenna Luisa Boccher

Edited by: Andrew Bongiovanni

Graphic by: Arsh Naseer

Introduction

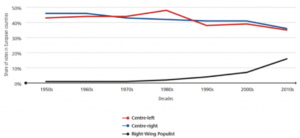

The specter of right-wing populism (RWP) looms large across the globe, reshaping political landscapes and challenging established norms.1 In Central and South America, however, this phenomenon appears particularly potent, fueled by a confluence of economic anxieties, social frustrations, and disillusionment with traditional politics. From Jair Bolsonaro’s fiery rhetoric in Brazil to Nayib Bukele’s unconventional leadership in El Salvador, right-wing populist leaders are capturing the imaginations of voters disenfranchised by stagnant economies, entrenched corruption, and rising inequality. This trend, far from being a transient wave, carries profound implications for the region’s democratic trajectory and necessitates a deeper understanding of its root causes and potential consequences.2

This analysis delves into the complex tapestry of factors driving the rise of RWP in Central and South America. We begin by unpacking the distinct characteristics of this phenomenon in the region, considering its historical context and diverse manifestations. Following that, we dissect the key economic, social, and political elements feeding into this populist surge, drawing upon recent data and scholarly perspectives. Ultimately, we turn our attention to the multifaceted implications of this trend for governance and democracy, exploring potential threats and opportunities for navigating this critical juncture.

Defining Right Wing Populism

A minimalist understanding of right-wing populism classifies it as movements, parties, leaders, and governments who engage in transgressive political performances that oppose ‘elites’ in the name of the ‘people,’ rely at least in part on unmediated communication between a leader and followers, and spread right-wing ideological messages such as anti-globalism, traditional social values, and ethnic or religious nationalism. ”3 – Anthony Pereira

Right-Wing Populism in Argentina, El Salvador, and Mexico – A New Generation Emerges

The tide of RWP in Central and South America continues to evolve, with a new generation of leaders emerging alongside established figures.4 This analysis focuses on three emblematic figures––Javier Milei of Argentina, Nayib Bukele of El Salvador, and Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) of Mexico––to illustrate the distinct yet overlapping characteristics of this phenomenon, particularly considering Milei’s recent rise to power.5,6,7

Anti-Establishment Iconoclasts

While different in age and background, these leaders share a core characteristic: a fiery anti-establishment message. Bukele, a millennial outsider, cast himself against the entrenched two-party system. AMLO, a veteran leftist turned populist, railed against the privileged elites. Milei, a self-described “anarcho-capitalist” and economist, stands out with his radical anti-state rhetoric, proposing to slash government spending, eliminate the Central Bank, and privatize key sectors. This extreme anti-establishment stance resonates with voters disillusioned with traditional politics and seeking drastic change.

Economic Discontent and Alternative Narratives

Economic anxieties play a significant role in their appeal. Bukele promised to revitalize the Salvadoran economy, while AMLO focused on social welfare programs. Milei, however, offers a starkly different approach, advocating for radical economic liberalism and minimal government intervention. This anti-establishment, pro-market narrative resonates with segments of the population dissatisfied with stagnant economies and perceived government inefficiencies.

Nationalism and Social Divisions

While not explicitly xenophobic, their narratives often carry nationalist undertones. Bukele emphasizes national pride and cultural identity. AMLO champions Mexican exceptionalism and criticizes foreign interference. Milei’s brand of nationalism focuses on “Argentine pride” but also carries socially conservative elements, opposing abortion and sex education. These narratives, although nuanced, potentially exacerbate social divisions and anxieties about immigration and cultural change.

Charismatic Leadership and Social Media Savvy

These leaders utilize social media effectively as a direct communication tool. Bukele and Milei have mastered platforms like Instagram and Twitter to bypass traditional media and connect directly with their supporters. AMLO holds daily press conferences and utilizes social media to engage with his audience. Their charismatic personalities and direct communication style endear them to sections of the population disillusioned with traditional political discourse. The rise of these leaders raises concerns for the future of democracy and individual rights. Bukele’s increasingly authoritarian actions are alarming, while AMLO’s weakening of independent institutions is worrying. Milei’s radical proposals, if implemented, could have significant economic and social repercussions. Understanding the shared characteristics and potential impacts of these diverse figures is crucial for navigating the complex political landscape of the region.

Commonalities Between Leaders

While these leaders differ in their approaches, they share a common thread of anti-establishment rhetoric, economic discontent, and nationalist narratives amplified by social media. Understanding these shared characteristics and their potential impact on democracy and individual rights is crucial for navigating the complex political landscape of the region, particularly as figures like Milei rise to power.

Examining the Causes

The rise of RWP has grown intertwined with the Latin American region, consistently fueled by discontent with economic opportunities, social anxieties, weak institutions, and the technology bridge linking RWP globally. The marketing of these fears draws on the rhetoric of left-wing economic ideas and electoral aspects of democracy to create a widely appealing message. The combination of these factors creates a perfect storm for charismatic personalities to entrap wide-ranging coalitions of citizens in voting for RWP leaders.

Economic Factors

Economic Factors

The framing of economic instability to gain public trust is a key RWP strategy. Leaders exploit fears and anxieties regarding unemployment, low wages, or income volatility. In Argentina, over 36% of the population lived below the poverty line in 2022, with food prices increasing by nearly 100% that year, creating desperation that Milei’s “shock therapy” policies exploited. His price controls froze utility rates and rent prices temporarily, creating an illusion of economic relief while paving the way for drastic austerity measures.8 This move consolidates power in Milei’s regime in Argentina and allows for him to push for more severe austerity measures such as a mandate that bypasses Congress, strips workers’ rights, and severely limits social welfare.

Social Factors

Like economic instability, social anxieties rooted in fear of losing power and position to marginalized groups are exploited by leaders. These may include perceived threats of multiculturalism, secularism, or gender and sexual equity, creating a harsh binary between “us” and “them.” Leaders utilize this nostalgia through emotional governance, continuously threatening one’s security with an out-group.9 They promise to return to the dominant culture and traditional modes of power. This is reflected in the rhetoric on the threat of social justice in Argentina; “Where there is a need, there is a right but they’re forgetting that somebody has to pay for that right. Its maximum expression is that aberration called social justice which is unjust because it implies unequal treatment in the face of the law,” Milei declared.10 His explicit use of transactional justice calls for a mobilization of the nation.

Political Disillusionment

Generalized political disenchantment stemming from a history of corruption, inefficiency, and disconnection between the government and the people allows RWP leaders to frame themselves as anti-elite and individualistic alternatives. The lack of robust checks on power, such as an independent judiciary, free press, and strong legislative bodies, is particularly dangerous as leaders exploit these institutional weaknesses to further their agendas and utilize militaristic power to carry out threats without oversight. By capitalizing on weak institutions during crises, RWP leaders can consolidate power, undermine democratic norms, and govern with impunity, shielded from meaningful oversight or consequences for abuses of power.11 This unrestrained environment is fertile ground for the rise of authoritarian tendencies under the guise of populist rhetoric. The COVID-19 pandemic heightened this trend, as some leaders assumed expanded powers in exchange for providing security. In El Salvador, President Bukele took advantage of a suspended parliament to enforce a militarized lockdown with near-absolute power. Heavily armed forces supervised compulsory stay-at-home orders, resulting in over 600 illegal detentions.12 The absence of checks on Bukele’s authority enabled widespread human rights violations without proper transparency or accountability mechanisms.

Implications and Policy Responses

The causes and prerequisites of RWP are diverse, but incredibly intertwined, as they all utilize a sense of fear to mobilize the public towards RWP. Economic anxiety is often based on the fears of social anxieties, which affects trust in the government to secure the dominant culture. RWP carries a tangible effect within societies even if it is voted in for a single term, as it focuses on dismantling democratic institutions, social polarization, and increased human rights violations.

Democratic Backsliding

Populism is as antithetical to democracy because of its focus on anti-pluralism and a singular, centralized leader. Populists’ goals supersede democracy’s limitations, necessitating the deconstruction of the previous system through cultural and structural overhaul. This results in an extreme police state where opposition is demonized. Populist leaders seek to erode public trust in electoral and democratic integrity, simultaneously discrediting dissent.13 They change rules like extending term limits, gerrymandering, and introducing voting restrictions to disadvantage the opposition. We see this in Mexico, where President Obrador has launched legislative reforms to cut the budget, staff, and independence of the respected National Electoral Institute (INE) ahead of the 2024 elections, marking a significant turn away from hard-won democratic gains. Despite protests, if Obrador continues disarming the public’s means to voice concerns, he could further centralize power.14

Social Polarization

Social polarization is a key strategy for building a strong RWP base, centering on an antagonistic, anti-compromising frontier between establishment and anti-establishment camps. This binary worldview complicates democratic institutions by characterizing the “other” as a threat. By generating new controversies on the political agenda, leaders redefine partisan bounds and electoral stakes. Portraying the fringe emboldens anti-populist sides to protest, further entrenching polarization into a zero-sum game favoring RWP.15 In Argentina, this is demonstrated through la grieta, or the rift between political factions. The stalemate has enabled Milei to push severe governmental reforms while retaining power. He utilized previous concerns around Kirchner governments to raise issues like big government, abortion, mandatory vaccinations, and climate change––items previously considered decided by consensus.16 This underscores how polarization has allowed Milei to shift traditional talking points to consolidate his RWP agenda.

Human Rights Abuses

Building on a weakened democratic state and social polarization, human rights abuses flourish under RWP due to the suspension of judicial oversight and the militarization of domestic policy. RWP favors short-term gains over long-term stability, emboldening leaders to seek unethical means to centralize support, deprive designated “others” of basic rights, and refuse to tackle root issues. The framing of human rights as an interference with the regime’s goals aids in garnering public support. This is exemplified in El Salvador under Bukele’s regime; leveraging fears of gang violence, Bukele has suspended due process and habeas corpus, enabling the mass arrest of citizens with alleged gang ties or associations. This abuse of emergency powers has resulted in the detention of thousands in inhumane “super-prisons” without trial, sometimes leading to the deaths of these individuals. This case highlights the dangers of unchecked RWP, where truth is scarce and the people suffer the consequences.17 Bukele has created a punitive policy that targets gang violence, but in doing so, has suspended the rights and civil liberties of Salvadoran citizens, capitalizing on public fears to consolidate power and deprive the “other” of their basic human rights.

There is no absolute answer to solving the crises that RWP present; that would require country-specific solutions that delve into each leader’s domestic and international relations. However, the three target goals of promoting good governance, combating misinformation, and recognizing public grievances provide benchmarks for future politician seeking to reverse the damage RWP has wrought.

Promoting Good Governance

While the sentiment of populism may already be present within society, right-wing populist leaders are often able to mobilize these sentiments through their ability to exploit the weakness of democratic systems. In addition, democratic leaders often face a deficit of trust and goodwill from the public in their ability to govern effectively. As such, it is preferable to avoid rhetoric and messaging that tie identity politics to partisan agendas in order to evade the traps of RWP.

Without strict in-group definitions, populist leaders will be unable to leverage divisive “us vs. them” language. This would also discourage the incorporation of minority rights, migration, and race as central campaign platforms––as these groups would be understood as a singular citizenry. Instead, a focus on creating a unified national vision can allow the leader to address the structural issues undermining trust in democratic institutions.18 This could involve strengthening an impartial judiciary, improving communication channels between citizens and government, and expanding social safety net programs. Additionally, parties need to create distinct platforms in order for voters to feel as if there is a feasible choice between candidates and to become more engaged in the electoral process.

Pursuing constitutional reforms that formally include all stakeholders can also demonstrate a commitment to a more inclusive and democratic future. This signals the government’s agreement with the diverse range of citizens and provides clear protections for a pluralistic system. Overall, this multi-pronged approach aims to rebuild public trust, empower democratic institutions, and address the root causes that enable RWP to take hold.

Combating Misinformation

The rise of RWP has been fueled by demagogic leaders leveraging polarizing rhetoric and spreading misinformation. Countering this will require a multi-pronged approach. On the supply side, governments must shore up the independence and credibility of democratic institutions, especially the media. This includes enacting robust protections for press freedom, providing public funding for fact-based journalism, and empowering media oversight bodies. Policymakers should also collaborate with digital platforms to implement stricter content moderation policies and increase transparency around political ads and algorithmic curation, with penalties for platforms that fail to curb misinformation. On the demand side, investing in media literacy education is crucial. Curricula should equip citizens with critical thinking skills to identify misinformation and verify credible sources. Partnerships with civil society can amplify these efforts within communities. Governments should also work to rebuild public trust by enhancing transparency, cracking down on corruption, and improving responsiveness to citizens’ concerns. International cooperation is essential to counter cross-border disinformation campaigns.19 Sharing best practices and coordinating sanctions on malign foreign actors can create a more resilient global information ecosystem. The goal is to create an environment where citizens can discern fact from fiction, and where purveyors of misinformation are denied the oxygen to thrive––a long-term battle critical to the future of democracy.

Recognizing and Addressing Public Grievances

The rise of RWP does not occur in a vacuum but rather is symptomatic of deeper systemic failures. Populist leaders exploit well-founded public concerns, capitalizing on the anxieties and frustrations of citizens who feel neglected or betrayed by the political establishment. To effectively counter this, future governments must be willing to directly confront and address the legitimate grievances that have given rise to populist sentiments. This requires a sustained, good-faith effort to improve the everyday lives of citizens through tangible, impactful policy changes. Crucially, this cannot be a top-down, technocratic approach. Governments must seek to uplift and empower grassroots community organizations as a direct conduit between the public and decision-makers.20 This two-way channel of communication and accountability is essential for rebuilding trust and ensuring policies reflect the real needs of the people.

On the political front, this may also necessitate the inclusion of right-wing populist parties in the electoral process, rather than attempts to exclude or marginalize them. While challenging, this can help undermine the populists’ narrative of persecution and isolation from the “corrupt system.” Constructive engagement, rather than outright rejection, can gradually erode their anti-establishment appeal. Ultimately, the key is a comprehensive, long-term strategy that combines institutional reforms, grassroots empowerment, and a genuine commitment to improving socioeconomic conditions for all citizens. Only by addressing the underlying drivers of disillusionment can governments hope to build the resilience to withstand the siren call of RWP.

Feasibility

The feasibility of effectively countering RWP is context-dependent, hinging on factors like the entrenched power of the populist leader, the resilience of democratic institutions, and the strength of civic engagement. As a foundation, leaders must first undo any reforms or institutional capture that enabled abuses under the previous populist regime. However, resource constraints and capacity will shape the scope of possible change. Another challenge is the risk of public backlash; overly rapid or drastic reforms could inadvertently fuel further RWP sentiment or a swing toward left-wing populism, a dynamic common in parts of Latin America. To bolster success, a balanced approach is crucial––shoring up independent, effective democratic institutions while also investing in public education, social services, and community empowerment. Improving quality of life can help erode the appeal of populist scapegoating. Ultimately, addressing RWP’s deep-seated drivers requires a comprehensive, context-specific strategy built on steady, incremental progress and broad civic support. There are no quick fixes, but the alternative is the further erosion of democracy.

Conclusion

The rise of RWP in Central and South America presents a critical juncture for examining the effectiveness and resilience of democratic institutions in the region. This phenomenon, driven by diverse factors such as economic dissatisfaction, social anxieties, and political disenchantment, compels a nuanced understanding and response. While these leaders have successfully harnessed widespread discontent to gain power, their governance also highlights significant challenges and opportunities for democracy. It is essential to critically evaluate both the appeals and the drawbacks of populist policies. Moving forward, fostering open dialogue, enhancing governmental accountability, and ensuring that economic and social policies are inclusive and equitable can help mitigate the risks of populism. Ultimately, a balanced approach that addresses the root causes of populist support while safeguarding democratic principles may provide the most sustainable path forward in these politically dynamic regions.

Works Cited

[1] Grzymala-Busse, Anna, Didi Kuo, Francis Fukuyama, and Michael McFaul. 2020. “Global Populisms and Their Challenges.” Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. March. https://fsi.stanford.edu/global-populisms/global-populisms-and-their-challenges.

[2] Casas-Zamora, Kevin. 2023. Look at Latin America. This is How TTDemocracies Fail. New York Times. April 13. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/13/opinion/international-world/democracy-latin-america.html.

[3] Pereira, Anthony W. 2023. Right-Wing Populism in Latin America and Beyond. New York: Routledge.

[4] Pereira, Anthony W. 2023. “Understanding Right-Wing Populism (or the Extreme Right).” Latin American Studies Association Forum. https://forum.lasaweb.org/files/vol54-issue4/dossier-3.pdf.

[5] Biller, David, and Daniel Politi. 2023. The lion, the wig and the warrior. Who is Javier Milei, Argentina’s president-elect? The Associated Press. November 20. https://apnews.com/article/javier-milei-profile-argentina-election-82488d49cca5aee10d4b911bde530922.

[6] Hassan, Tirana. 2023. El Salvador Events of 2022. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/el-salvador.

[7] Birke, Sarah. 2021. Mexico’s president will continue to damage the country’s democracy. The Economist. November 8. https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2021/11/08/mexicos-president-will-continue-to-damage-the-countrys-democracy?ppccampaignID=&ppcadID=&ppcgclID=&utm_medium=cpc.adword.pd&utm_source=google&ppccampaignID=17210591673&ppcadID=&utm_campaign=a.22brand_pm.

[8] Kozul-Wright, Alexander. 2024. “First 100 Days: Milei Falters on Shock Therapy for Argentina’s Economy.” Al Jazeera. March 19. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2024/3/19/first-100-days-milei-falters-on-shock-therapy-for-argentinas-economy.

[9] Kinnvall, Catarina, and Ted Svensson. 2022. “Exploring the Populist ‘Mind’: Anxiety, Fantasy, And …” Sage Journals. February 24. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/13691481221075925.

[10] Grainger, James. 2023. “Javier Milei and His Beliefs – in His Own Words.” Buenos Aires Times, August 19. https://www.batimes.com.ar/news/argentina/javier-milei-and-his-beliefs-in-his-own-words.phtml.

[11] Wolf, Sonja. 2021.“A Populist President Tests El Salvador’s Democracy.” University of California Press, February 1. https://online.ucpress.edu/currenthistory/article/120/823/64/115918/A-Populist-President-Tests-El-Salvador-s-Democracy.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Halikiopoulou, Daphne, and Tim Vlandas. n.d. “Understanding Right-Wing Populism and What to Do about It.” Right-wing populism. Accessed April 18, 2024. https://democracy.fes.de/topics/right-wing-populism.

[14] Fabbro, Rocio. 2023. “López Obrador’s Reforms Threaten Mexican Democracy.” Foreign Policy, March 23. https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/03/23/lopez-obrador-electoral-reforms-mexico-democracy-ine/.

[15] Roberts, Kenneth M. 2022. “Populism and Polarization in Comparative Perspective: Constitutive, Spatial and Institutional Dimensions.” Government and Opposition 57, no. 4: 680–702. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.14.

[16] Iglesias, Fernando. 2022. “La Grieta, Un Término Inapropiado Para La Realidad Política Argentina.” LA NACION, September 15. https://www.lanacion.com.ar/opinion/la-grieta-un-termino-inapropiado-para-la-realidad-politica-argentina-nid15092022/.

[17] Kinosian, Sarah. 2022. “Trolls, Propaganda & Fear Stoke Bukele’s Media Machine in El Salvador.” Reuters, November 29. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/el-salvador-politics-media/.

[18] Kendall-Taylor, Andrea, and Carisa Nietsch. 2020. “Combating Populism.” Center for a New American Security (en-US), March 19. https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/combating-populism.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

Author Bios:

Jenna Boccher is a third-year college student of Puerto Rican and Italian descent. She is currently pursuing a degree in International Relations, Latinx Studies and Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. After obtaining her bachelor’s degree, she plans to enter public service with a focus on policy analysis and research in Latin America and the Caribbean. Jenna is currently a research assistant at The Ramos Research Institute. Her passion lies in empowering individuals to reclaim their agency & instigate meaningful change.