By: Yiming Zhong

Edited By: Andrew Bongiovanni

In the face of an existential threat, the world seems to finally be turning towards a sustainable future. The growing demand for environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing and climate finance has made it clear that the financial sector must adapt to this new reality. The United States, in particular, is lagging behind, with its carbon market still in its infancy compared to China’s burgeoning carbon trading market.1 As the global economy pivots towards sustainability, it is imperative that countries, and particularly the United States, develop a comprehensive strategy to address the intersection of ESG investing, climate finance, and economic security. The consequences of inaction will be catastrophic, whereas a proactive approach will yield a more resilient and sustainable future for all.

The race for sustainable finance is not only about addressing climate change but also about securing economic and climate security. China and the EU are leading the way with robust sustainability regulatory frameworks, such as the EU’s Taxonomy Regulation and China’s upcoming sustainability disclosure standards aligned with ISSB by 2030.2 Foreign entities might face challenges and resource constrains by complying with the local disclosure standards. Many US small and medium enterprises (SMEs) have already faced challenges in ESG compliance. The challenges manifest in resource constrains, data privacy concerns, and confusion on standards and methodologies.

If the United States battens down the hatches against the carbon market, Beijing will become the new Wall Street for the carbon trade. China, as the top polluter with 11.4 billion metric tons of GHG emissions, allocated its 225-255 million metric tons of carbon emissions annually through a voluntary carbon credit trade program3; its potential impact may bear on global climate cooperation and the global carbon market. In 2024, China’s launch of the CCER program further cemented its leadership in carbon trading.4

Growing Market with Active Changes

According to a 2022 Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA) report,5 global sustainable investing assets have grown dramatically over the past decade. Despite the regulatory changes in 2020, EU sustainable assets in 2023 recovered to 2018 levels. The US market for sustainable investments has dropped materially from US$17.1 trillion to US$8.4 trillion due to methodology changes.6 Over the past eight years, sustainable assets have averaged 22.4 percent of total assets under management (AUM).7 In 2022, global sustainable assets increased by 38.3 percent––an US$8 billion growth excluding the US region.8

Millennials are taking a firm grip on investment directions. Representing 75 million people in the United States, millennials are anticipated to inherit an estimated US$30 trillion in wealth from baby boomers.9 MSCI research reveals that 88 percent of high-net-worth millennial investors prioritize reviewing ESG reports and related information before making investment decisions.10 Bank of America predicted that over the next 2-3 decades, millennials could invest between US$15-20 trillion in US-domiciled ESG investments, potentially doubling the size of the entire US equity market.11

Given the polarized nature of climate change in US politics, the risk of insufficiently responding to these challenges could prove significant. ESG investing and climate finance are crucial components of a green and sustainable economy. The market seeks clarity on who has the authority to define climate finance, what qualifies as sustainable assets, and how the underlying processes and methodologies function. The foundations of emerging green financial instruments as well as corporations considering meeting carbon emissions goals include carbon emission calculations, price setting, ESG disclosure and regulations, and monitoring systems, among others. The emerging regulatory bodies and groups are attempting to steer the course of the green economy by way of their definitions and regulations that will shape it.

Global Pivot to Sustainability

Financial institutions in the United States are considering the trend of investment. According to Morgan Stanley, sustainable funds returned to their long-term trend of outperformance in 2023, generating a median return of 12.6 percent, nearly 50 percent ahead of traditional funds.12 While the US hesitated, China and EU are taking more affirmative actions. On May 27, 2024, China’s Ministry of Finance opened a public consultation on the Exposure Draft of the Chinese Sustainability Disclosure Standards for Businesses.13 This document indicated China intends to create a mandatory system aligned with the International Sustainability Standard Board (ISSB) by 2030, setting fundamental sustainability and climate-related disclosure standards by 2027.14

In 2020, the EU Parliament approved the EU Taxonomy Regulation, which aims to define environmentally sustainable economic activities and to reduce the greenwashing of financial products. In 2021, the EU published Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) to help institutional asset owners and retail clients compare, select, and monitor the sustainability characteristics of investment funds. The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) took effect in 2023, requiring eligible companies to issue annual sustainability reports.15

The race for sustainable finance is not merely about addressing climate change and meeting the net zero goal; it is a battle for dominance over the emerging industry of sustainable finance. Those who establish and enforce disclosure standards and methodologies will steer the global economy toward sustainability.

Sustainable Finance = Economic and Climate Security

Foreign entities investing or establishing an office in the EU must comply with the CSRD under certain criteria.16 China may develop similar requirements for foreign investors. Proprietary data needs to be audited, carbon emissions determined by local methodology; and green and sustainable classifications dominated by the regulatory bodies.

Data Disclosure

The degree of data an entity discloses is informed by financial materiality. Short-term or long-term finance-related data must be disclosed. Regulatory bodies and auditing firms will play a significant role in the data selection and examination process. Foreign entities must decide how much information to disclose under EU ESG requirements. Currently, at least 10,000 foreign companies are affected by EU sustainable rules, with American entities making up a third of them.17

Resource Constrains

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) face challenges in disclosing comprehensive ESG reports because of limited financial resources and professional personnel compared to listed enterprises. The complexity of ESG data collection, analysis, and reporting can be a significant burden. ESG disclosure requirements might limit opportunities in foreign trade, sustainable finance, investment, and subsidies. SMEs may face disadvantages compared to EU and Chinese counterparts with better access to relevant resources.

Rules Setting

China and Europe lead in setting standards for sustainable finance and carbon trading, similar to China’s dominance in the critical minerals sector.18 If US private entities remain reluctant, China will continue to lead, evidenced by its control over the critical minerals supply chain. Competition over metrics and methodologies in sustainable finance and emissions scenarios will determine who controls this emerging industry. Rule-setting is crucial for dictating the global economic landscape and ensuring long-term security in climate and economic realms.

Beijing Green Exchange – The New Wall Street for Carbon?

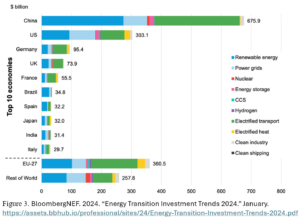

China is the largest market for energy transition investment, reaching US$676 billion in 2023.19 It is 38 percent of the global energy transition investment and more than double the United States’ investment.20 As an active participant in carbon mitigation, China explores opportunities to transform its status as the largest emitter into significant advantages.

On January 22, 2024, China launched the China Certified Emission Reduction (CCER) program, incentivizing industries to trade carbon reduction credits voluntarily.21 The program focuses on forestation, mangrove cultivation, solar thermal power, and grid-connected offshore wind power projects, as the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) released methodologies for these industries in 2023.22

If only counting the Chinese emission trade system (ETS) launched in 2021 with limited designated emission quotas for the power plant industry,23 it stands as the largest carbon trading market by GHG emissions volume in the world.24 The CCER, in the long run, might become a monopolized market, giving powerful firms the ability to set the price of global carbon emissions. It can, on one hand, increase the emission costs for high-emission enterprises, and on the other, provide additional revenue for new energy and low-carbon assets, forming a positive cash flow that brings new vitality to China’s carbon market.

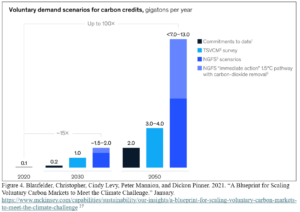

Most academic and market participants are bullish on the potential of the carbon market. McKinsey estimates annual global demand for carbon credits could reach up to 1.5 to 2.0 gigatons of carbon dioxide (GtCO2) by 2030 and 7 to 13 GtCO2 by 2050.25 Accenture reports that carbon markets could become a US$2 trillion physical market by 2050 and more than a US$10 trillion traded market when considering derivatives, with an expected carbon price of US$120 per ton.26

Until 2021, there were 65 carbon pricing initiatives implemented or scheduled. 35 of them are carbon taxation-based and 30 of them are ETS mechanism-based. They cover approximately 22 percent of global GHG emissions and are responsible for raising US$53 billion in revenue.28

Currently with the carbon market only including the power sector, the theoretical maximum annual demand for CCER is around 225-255 million metric tons,29 valued at 12.889 billion yuan (US$1.8 billion).30 Although the global carbon market value hit US$949 billion in a record high in 2022,31 Chinese carbon emissions alone were 11.4 billion metric tons––more than the those of Europe (5.62 billion) and the United States (5.06 billion) combined.32 Massive demand in the carbon trade will lead carbon pricing and the carbon trade market towards Beijing’s vision, aligning with the Fourteenth Five-year Plan to lead global climate cooperation and strengthen South-South Cooperation. China, with its high carbon emissions, transforms this into an advantage, potentially manipulating the global carbon market.

To be Green or Not to be Green, that is the Question

It is not a question of whether the United States should prioritize sustainable finance, but rather whether it chooses to prioritize the well-being of the planet alongside its own economic interests. The consequences of inaction will be dire, as the very foundations of the global economy and way of life are built upon the unsustainable practices of the past. The question is no longer whether we can afford to be green, but whether we can afford not to. After all, what are the alternatives?

Works Cited

1. BloombergNEF. 2018. “China’s Carbon Market Shows How U.S. Is Falling Behind: Q&A.” January 4. https://about.bnef.com/blog/chinas-carbon-market-shows-how-u-s-is-falling-behind-qa/

2. Interesse, G. 2024. “China Releases ESG Reporting Standards for Businesses.” China Brief, June. https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-releases-esg-reporting-standards-for-businesses/#:~:text=China%20released%20a%20new%20set,support%20sustainable%20development%20goals%20nationwide

3. Research Institute of Carbon Neutrality. 2024. https://ricn.sjtu.edu.cn/Web/Show/1207

4. Liang, Shuang. 2024. “Revamped Carbon Credit Trade System Launched.” China Daily, January. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202401/23/WS65af2862a3105f21a507dd42.html

5. Global Sustainable Investment Alliance. 2023. “Global Sustainable Investment Review 2022.” https://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/GSIA-Report-2022.pdf

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Morgan Stanley. 2015. “The $30 Trillion Challenge.” April 28. https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/30-trillion-challenge

10. MSCI ESG Research LLC. 2020. “Swipe to Invest: The Story Behind Millennials and ESG Investing.” March. https://www.msci.com/documents/10199/07e7a7d3-59c3-4d0b-b0b5-029e8fd3974b

11. Betts, D., R. Gordon, A. Egizi, and C. Cruse. 2021. “The Future of the Public’s Health.” November. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/health-care/the-future-of-public-health.html

12. Institute for Sustainable Investing. 2024. “Sustainable Funds Outperformed Peers in 2023.” Morgan Stanley, February. https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/sustainable-funds-performance-2023-full-year

13. Interesse, G. 2024. “China Releases ESG Reporting Standards for Businesses.”

14. China’s Ministry of Finance. 2024. “Corporate Sustainability Disclosure Standards – Basic Guidelines (Draft for Public Consultation).” May. https://upload.news.esnai.com/2024/0527/1716799385429.pdf

15. The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive. 2022. “Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022.” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022L2464

16. Detailed Criteria

- Over 250 employees

- More than 40€ million in annual revenue

- More than 20€ million in total assets

- Publicly-listed equities and have more than 10 employees or 20€ million revenues

- International and non-EU companies with more than 150€ million annual revenues within the EU and which have at least one subsidiary or branch in the EU exceeding certain thresholds Any EU company that meets those criteria is required to file an annual report using the CSRD’s forthcoming sustainability taxonomy on how sustainability influences their business, as well as the company’s impact on people and the environment.

17. Holger, D. 2023. “At Least 10,000 Foreign Companies to Be Hit by EU Sustainability Rules.” April. https://www.wsj.com/articles/at-least-10-000-foreign-companies-to-be-hit-by-eu-sustainability-rules-307a1406

18. Sadden, E., and L. Chen. 2024. “China’s Critical Minerals Dominance and the Implications for the Global Energy Transition.” October. https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/podcasts/platts-future-energy/102324-chinas-critical-minerals-dominance-and-the-implications-for-the-global-energy-transition

19. BloombergNEF. 2024. “Energy Transition Investment Trends 2024.” January. https://assets.bbhub.io/professional/sites/24/Energy-Transition-Investment-Trends-2024.pdf

20. Ibid.

21. Wu, Y. 2024. “Understanding the Relaunched China Certified Emission Reduction (CCER) Program: Potential Opportunities for Foreign Companies.” China Briefing, May. https://www.china-briefing.com/news/understanding-the-relaunched-china-certified-emission-reduction-ccer-program-potential-opportunities-for-foreign-companies/

22. Yin, I. 2024. “Commodities 2024: China’s Domestic Carbon Market Set for Revamp; Article 6 in Limbo.” S&P Global, January. https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/energy-transition/011724-chinas-domestic-carbon-market-set-for-revamp-in-2024-article-6-in-limbo

23. International Carbon Action Partnership. n.d. “China National ETS.” https://icapcarbonaction.com/en/ets/china-national-ets

24. Xue, Y. 2023. “Poor Data Quality and Low Auction Levels Are Key Hurdles in China’s National Carbon Trading Market.” July. https://www.scmp.com/business/article/3228893/poor-data-quality-and-low-auction-levels-are-key-hurdles-chinas-national-carbon-trading-market

25. Blaufelder, Christopher, Cindy Levy, Peter Mannion, and Dickon Pinner. 2021. “A Blueprint for Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets to Meet the Climate Challenge.” January. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/a-blueprint-for-scaling-voluntary-carbon-markets-to-meet-the-climate-challenge

26. Kose, Ogan, Miguel G. Torreira, Mauricio Bermudez Neubauer, Louise Quarrell, and Ilias Sarris. 2023. “Harnessing the Power of Voluntary Carbon Markets.” Accenture. https://www.accenture.com/content/dam/accenture/final/accenture-com/document/Accenture-The-Carbon-Markets-POV.pdf

27. These amounts reflect demand established by climate commitments of more than 700 large companies. They are lower bounds because they do not account for likely growth in commitments and do not represent all companies worldwide. TSVCM = Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets. These amounts reflect demand based on a survey of subject-matter experts in the TSVCM. NGFS = Network for Greening the Financial System. These amounts reflect demand based on carbon-dioxide removal and sequestration requirements under the NGFS’s 1.5°C and 2.0°C scenarios. Both amounts reflect an assumption that all carbon-dioxide removal and sequestration results from carbon credits purchased on the voluntary market (whereas some removal and sequestration will result from carbon credits purchased in compliance markets and some will result from efforts other than carbon-offsetting projects).

28. Research Institute of Carbon Neutrality. 2024.

29. China Energy News. 2023. July. https://www.cpnn.com.cn/news/zngc/202307/t20230720_1619578.html

30. Twidale, Susanna. 2024. “Global Carbon Markets Value Hit Record $949 Billion Last Year – LSEG.” February. https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/global-carbon-markets-value-hit-record-949-bln-last-year-lseg-2024-02-12/#:~:text=LONDON%2C%20Feb%2012%20(Reuters),at%20LSEG%20said%20on%20Monday

31. Ritchie, Hannah, and Max Roser. 2020. “CO2 Emissions.” Our World in Data, June. https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions

32. Climate Watch. n.d. “Historical GHG Emissions.” https://www.climatewatchdata.org/ghg-emissions?end_year=2021&start_year=1990