Source: Associated Press

Written by: Elisabeth Lembo

Edited by: Eghosa Asemota

In a 2016 report, the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) declared that the “promise of Brown v. Board of Education is unraveling.”[1] Across the country, white and Asian students are enrolled in schools of predominantly middle-class socioeconomic status, while Black and Latino students are increasingly enrolled by large percentages among peers from low socioeconomic backgrounds. According to a study at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), the proportion of Black and Latino students enrolled in resource-poor public schools (where seventy-five to 100 percent of students qualify for price-reduced lunch) increased by eleven percent from 2011 to 2014.[2] Typically, schools with less resources have less experienced teachers, fewer curricular options, and structurally poor facilities. Ultimately, the facts that led justices in Brown v. Board of Education to rule that segregated schools are inherently unequal prove to remain just as true today as they did in 1954.[3]

This “resegregation” along racial and socioeconomic lines in schools often mirrors the income segregation seen in neighborhoods across the United States. It is critical to consider these divides. As shared by Kendra Bischoff and Sean Reardon in their article “Residential Segregation by Income, 1970-2009,” “neighborhood composition— particularly neighborhood poverty and concentrated economic disadvantage— will affect residents’ social, economic, educational, psychological, and physical outcomes through a variety of mechanisms.”[4] In order to address the “unraveling” of Brown v. Board of Education, it is necessary to explore the implications of housing and school segregation across the country.

Past Supreme Court Rulings

The current high rates of school segregation may be attributed – among many factors – to a series of Supreme Court cases from the 1970s through the end of the 1990s that have impeded desegregation efforts. During this time, various rulings set precedents that decreased the federal government’s control over busing and district funding policies. Without clear federal regulations, integration efforts declined as local districts lost their authority to implement and advance them. One of the most formative rulings against desegregation efforts in recent years came in the Supreme Court’s 2007 case Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 when the Court determined that public schools may not use race as the sole determining factor for assigning students to schools. As districts lost their power to implement integration policies on the basis of race, only the most committed districts prevailed in their efforts.[5]

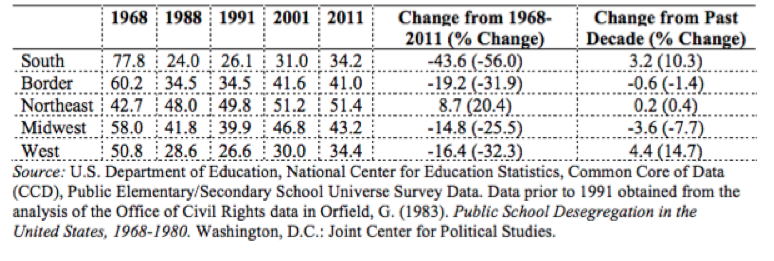

Because of these court rulings, several school districts have seen a decrease in diversity and an increase in school segregation. These trends have been most apparent after districts are deemed “unitary” (that is, when they have been deemed to have eliminated the effects of past segregation to a practicable extent). When courts declare a school system unitary, the federal system may no longer supervise the district’s student assignment and many districts regress into segregation. In the case of Miami-Dade County, Florida, for example, the exposure of Black students to white students decreased from six and a half percent in 2001, to fewer than five percent in 2011.[6] This “resegregation” is seen across the country (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of Black Students in Ninety to 100 percent Minority Schools

Discriminatory U.S. Economic Policies and the Racial Wealth Gap

The resegregation of American schools is not exclusively attributable to Supreme Court rulings. Decades of social and economic policies have played a role in stagnating the wealth of targeted American subgroups, particularly Black families. Conversely, for white families, policies have aided in their economic mobility.[7] According to the 2017 Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances, the median white family held thirteen times more net wealth than the median Black family, and ten times more wealth than the median Latino family.[8] Policies implemented in the twentieth century have caused lasting impacts on the relative wealth of minority communities. When the 1974 Supreme Court case Milliken v. Bradley ended inter-district bussing, many white families used their relative wealth to their advantage and moved to the suburbs in order to dodge integration in city schools. These policies and practices played a strong role in shaping the fabric of American public schools. By the 1980s, whites made up less than one third of the students in schools across Baltimore, Dallas, Detroit, Houston, and Memphis. Overall, as the racial and socioeconomic fabric of neighborhoods changed, it became difficult to legislate integration policies when there were simply not enough white students attending public schools.[9]

Policy Recommendations

There is an urgent need for action that tackles the emergence of resegregation in the United States. A public discussion of school integration along with policies that increase neighborhood diversity, enhance district autonomy, and promote socioeconomic diversity in schools are needed to address this intensifying issue properly.

Spark a National Discussion on School Integration

During the Civil Rights Era— a decade-long struggle for equal legal and constitutional rights across races— school integration was a popular topic in civil discourse. The era was marked by frequent discussions prompted by the 1954 Brown ruling among policymakers, activists, researchers, and civil society actors about the benefits of school integration. The federal government supported these conversations too. Federal support of these conversations has waned in the last few decades. “Racial Isolation in Public Schools,” a report published in 1967 during the Lyndon B. Johnson presidential administration, was the last federally funded report that detailed the costs of segregation and proposed evidence-based and data-driven solutions. In 1981, the Reagan administration ended the last federal program that offered research, evaluation, and training on how to advance desegregation in schools.[10] By ending federal-backed research, the United States’ education system has failed to keep pace with current realities. A public discussion that is grounded in data collected through federally-supported research and evaluation, and engages policymakers, civil society actors, and additional stakeholders is the first step toward the achievement of socioeconomically integrated schools.

Consider the Role of Neighborhood Diversity

While schools may consider integration within their buildings, it is also necessary to consider the current state of geographical segregation that continues to exist across the United States. Discussions about the socioeconomic diversity of schools should acknowledge the fact that high-income communities have newer schools with better funding and resources, while the opposite is true for low-income neighborhoods, where neighborhood schools are poorly funded.[11] According to a study by Reardon and Fox, between 1980 through 2010, levels of residential economic segregation have grown in neighborhoods across the country, while racial segregation has barely changed.[12] In order to address this, it will be important for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to take on a more comprehensive policy framework that understands the value of diverse neighborhoods from a racial and socioeconomic perspective. Ideally, bureaucrats from HUD tasked with implementing equitable housing policy should be involved in policy discussions about the best approaches to school integration.

Promote Socioeconomic Diversity in Schools

Considering the opportunities and barriers to socioeconomic approaches to school integration, assessing integration on a district-to-district basis may be more effective. This theory has been proposed and promoted by Richard D. Kahlenberg of The Century Foundation. Currently, there are over eighty districts across the United States educating over four million students that have implemented individualized processes that foster socioeconomic school integration. For example, in Dallas, Texas, schools are forty-five percent Latino, twenty-five percent Black, thirty-five percent white, and five percent Asian. Seeking to increase the racial diversity of their schools, Dallas developed a “block” approach to categorize families according to their neighborhood of residence (among other data) in order to develop optional “choice” schools for families to enroll their children in. In this system, Block One represents the wealthiest quartile of Dallas neighborhoods, Blocks Two and Three are middle-income families, and Block Four is the poorest quartile. Schools have been created which represent an integrated mix of students from all blocks.

This Dallas model has been successful so far because these “choice schools” perform well and have a large waiting list of students from all four blocks. Individualized school choice processes would be more effective than a top-down initiative from the federal level because they allow districts to develop more community-centric and responsive approaches. Dallas’s model was developed after the locality conducted a survey asking families if they would be willing to leave their zoned school district so long as transportation was offered. After the district learned that over seventy percent of families would leave their district for a new school if they received transportation, the district began to develop schools tailored to the interests of families, focusing on areas such as engineering, the arts, and languages.[13]

Decades ago, while delivering his dissenting opinion in Milliken v. Bradley, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall shared, “Unless our children begin to learn together, there is little hope that our people will ever begin to live together.” Contrary to Marshall’s words, the levels of school segregation and inequality that prompted Brown in 1954 are still seen today. In order to address this problem, there ought to be a nation-wide conversation about the benefits of diversity in schools, and more efforts to craft integrated housing policies as well as school integration policies which consider socioeconomic status in order to ensure that all students have access to resource-rich schools. Then, as school districts are empowered to navigate approaches to integration which are similar to those efforts made in Dallas, Texas, students will have the opportunity to learn alongside peers from different racial and economic backgrounds and enjoy a robust, stimulating educational experience.

References

- Petrella, Christopher. “The quiet resegregation of America constitutes a national crisis.” 2017.Accessed December 11, 2018, fromhttps://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/resegregation-america-ncna801446 ↑

- Richard Kahlenberg.. Why Economic School Segregation Matters. (2014). http://furmancenter.org/research/iri/essay/why-economic-school-segregation-matters. ↑

- McDaniels, A. (2018). 64 Years After Brown v. Board, Progressive Leaders Must Act on Segregation. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-k-12/news/2018/05/17/451027/64-years-brown-v-board-progressive-leaders-must-act-segregation/ ↑

- Kendra Bischoff, Sean Reardon, Residential Segregation by Income, 1970-2009. (2014) ↑

- Erwin Chemerinsky, The Segregation and Resegregation of American Public Education: The Courts’ Role, (2003). https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1712&context=faculty_scholarship. ↑

- Gary Orfield, Erica Frankenberg, Jongyeon Ee and John Kuscera, Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future, (2014). https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/brown-at-60-great-progress-a-long-retreat-and-an-uncertain-future/Brown-at-60-051814.pdf ↑

- Richard Kahlenberg, Why Economic School Segregation Matters, (2018). http://furmancenter.org/research/iri/essay/why-economic-school-segregation-matters. ↑

- Petrella, The quiet resegregation. https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/resegregation-america-ncna801446 ↑

- Chemerinsky, The Segregation and Resegregation. https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1712&context=faculty_scholarship. ↑

- Orfield, et. al, Brown at 60. https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/brown-at-60-great-progress-a-long-retreat-and-an-uncertain-future/Brown-at-60-051814.pdf ↑

- Kneebone, The Growth and Spread of Concentrated Poverty, 2000 to 2008-2012. http://www.brookings.edu/research/interactives/2014/concentrated-poverty#/M10420 ↑

- Reardon, Fox, townsend, Neighborhood Income Composition by Race and Income, 1990-2009. ↑

- Kahlenberg, Why Economic School Segregation, http://furmancenter.org/research/iri/essay/why-economic-school-segregation-matters ↑