edited by Arpit Chaturvedi

What is education? And what is the purpose of education? These questions have been pondered by a spate of philosophers and policymakers since the beginning of the civilized world. Perhaps the best answer to the latter question was provided by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in a 1947 campus newspaper (The Maroon Tiger) of the Morehouse College. King put it simply: education “has a two-fold function to perform in the life of man and in society: the one is utility and the other is culture”. This Ancient Indian deliberation on this matter is also profound and perhaps much deeper in its philosophical analysis which weaves the dual purpose of education into a coherent philosophical thread:

“Vidya dadati vinayam vinayad yati patratam

Patratvad dhanam apnoti dhanad dharmam tatah sukham”

[Education leads to sensibility, sensibility attains character/qualification, from that comes wealth and from wealth (one does) good deeds, from that (comes) joy]

-Hitopdesha, Text 6

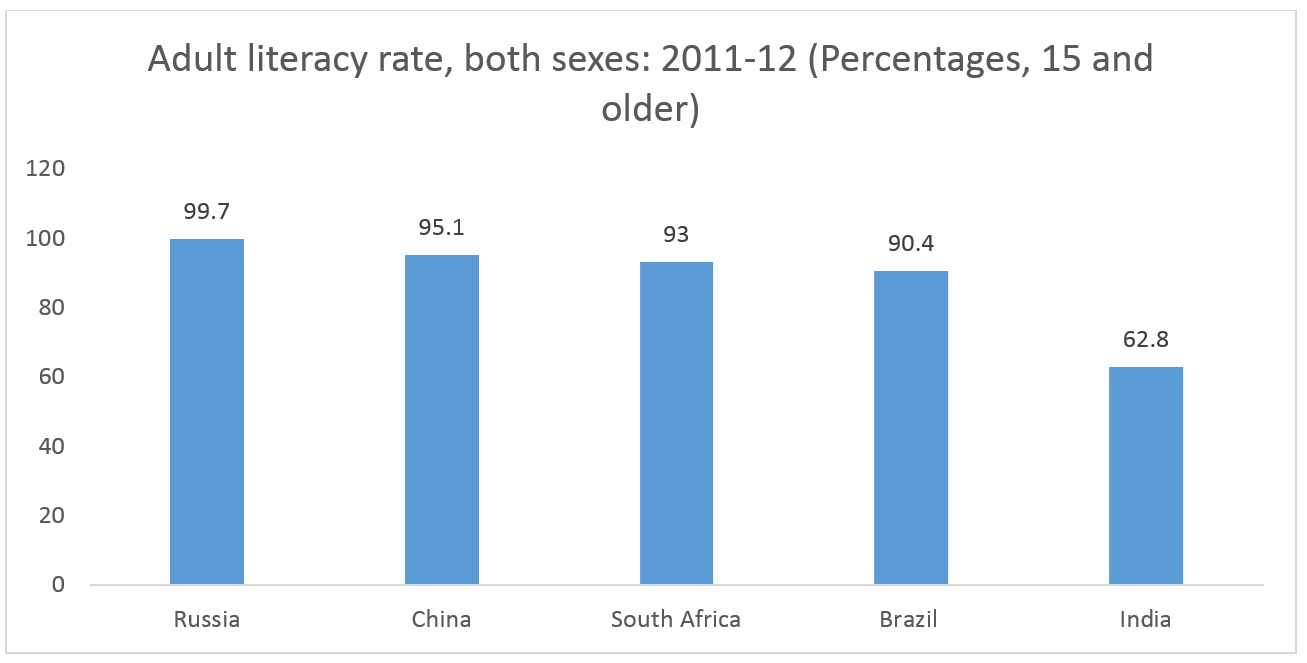

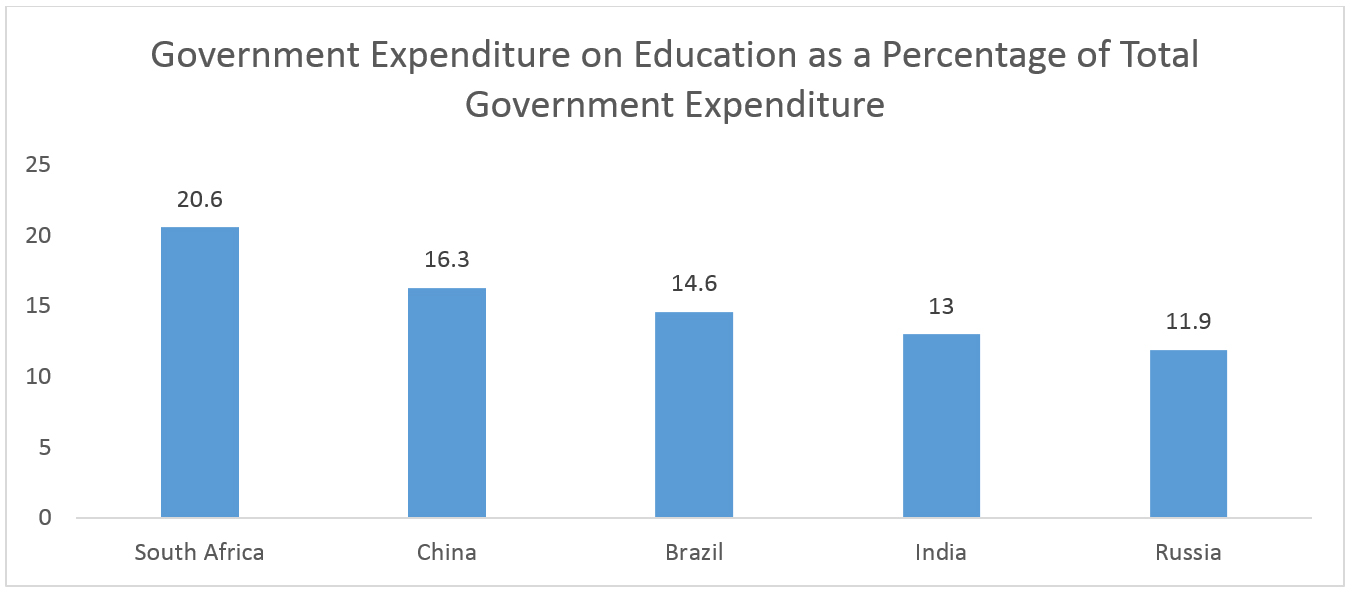

Education clearly is at the base of social good and development. The Swedish Nobel Laurate economist Karl Gunnar Myrdal has aptly analyzed that “Countries are underdeveloped because most of their people are underdeveloped, having had no opportunity of expanding their potential capital in the service of society.” Taking this argument forward, one cannot fail to observe that public spending on education; according to the World Bank, the total percentage of India’s GDP committed to education was last measured at 3.35 in 2012. By contrast, in 2010, 4.9% of the world’s GDP was spent on education. Comparing the expenditure on education in India with that of the rest of the world may not be a fair criterion considering the variances in development stages achieved by different nations, wherein the developed nations that experienced industrialization earlier have subsequently enjoyed a substantial advantage. Yet it would only be fair to compare the state of education and literacy in India with other BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) nations. Based on literacy rates, India stands at the lowest position among all BRICS nations:

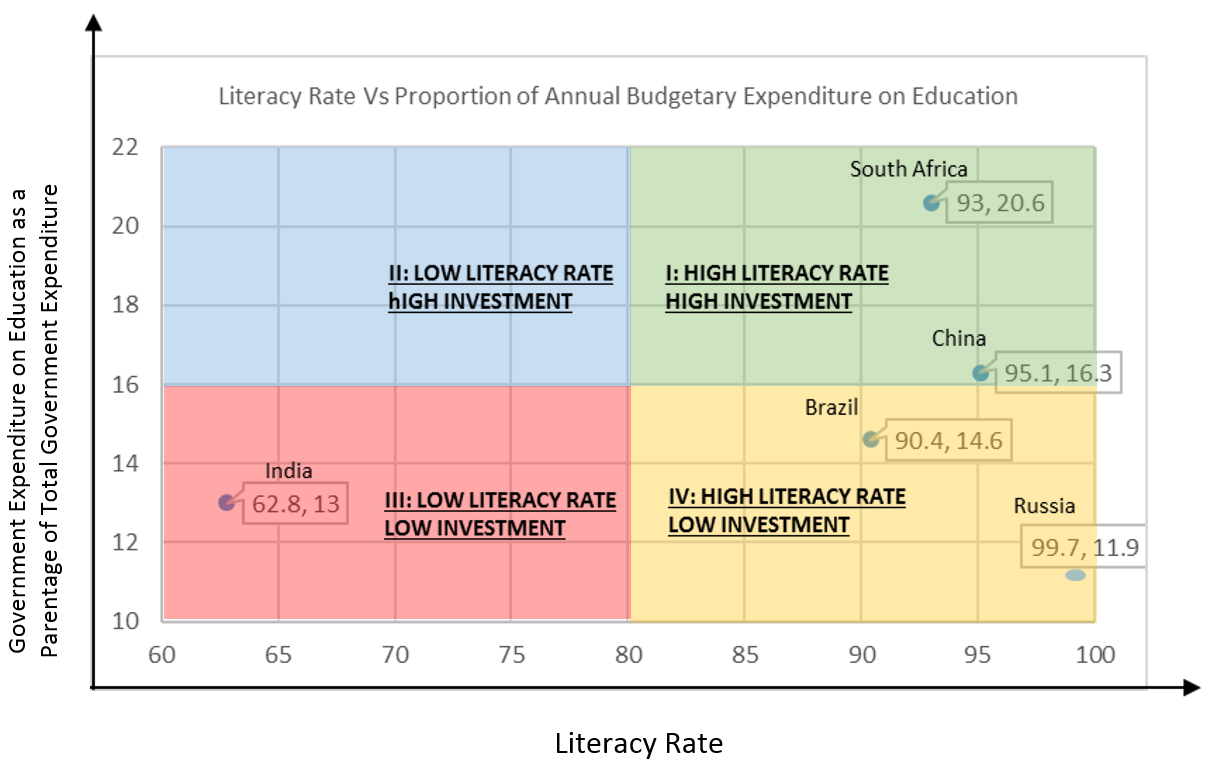

Observing the above data, I analyzed all the BRICS nations by distributing them into four categories or four quadrants on the basis of their literacy levels (x axis) and proportionate expenditure on education (y axis). The outcome of my analysis was the revelation that:

- No nation of the BRICS countries fell into the quadrant characterized by low literacy rate and high investment on education;

- South Africa and China had had high literacy rate and high investment (budgetary expenditure) on education;

- Brazil and Russia had high literacy rates and low expenditures on education (measured as percentages of their national GDPs);

- India fell into the low literacy rate-low investment quadrant; i.e. the literacy rate in India is among the lowest in all BRICS nations, at 62.8%, and its proportionate budgetary expenditure on the education sector is also comparatively low (13.7%).

The pictorial graph of the analysis is given below:

In the financial year 2015-16, the government of India reduced its expenditure on education by 16%; as if to play on the short memory of the public, the government then increased it by 4.9% the next year (2016-17 budget), accepting public praise for increasing expenditure on the education sector. The Finance minister’s promise of having a school within 5 km radius of every child seems like an unattainable dream on part of the Indian nation given the current policies.

What is the way out in such a situation? Under the burden of abysmally low developmental numbers coupled with a lack of political will to ameliorate the situation, one may be tempted to despair of the system and its way of functioning. However, India doesn’t need to look outside for examples of successful educational policies: the scientific procedure of learning from something about the macrocosm from the microcosm can be applied here. Some of the Indian states, such as Kerala, have historically been able to implement a seamlessly effective educational policy, which reflects in their higher figures on the Human Development Index.

In recent times, my home state of Telangana has come up with innovative and committed policies to enhance the quality as well as the coverage of education. On the 125th birth anniversary celebrations of architect of the Constitution (Dr. BR Ambedkar), my father Hon’ble Chief Minister of Telangana- Shri K. Chandrashekar Rao – launched the “KG to PG free education scheme,” which intends to analyze the current state of education and literacy levels in the state and to offer universal free education, from the kindergarten to the post-graduate level, with a special emphasis on including into mainstream education scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, and minority groups. Research by Jere Behrman and Nancy Birdsall[2] and other economists has shown that at times, in the absence of an emphasis on social inclusion, increased investments in education may result in increased social disparities; hence, policy-makers in Telangana have prioritized inclusion of deprived social groups while reforming the state’s education policies. Scholarships for scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, other backwards castes and minority students, along with free hostel facilities for girls belonging to such minority groups, are testimony to the inclusive philosophy of the state government.

What is more, the focus on mainstreaming has been kept unwavering; compulsory teaching of the English and Hindi languages in every school has been emphasized under such a scheme. Additionally, as a newly formed state in India, Telangana has set for itself an ambitious goal of having a school in each constituency; the state government is focused on not only spending all of its education budgets on infrastructural development, but rather on funding increased quality of education to enable the best of the minds to thrive. Indeed, in times to come, the nation and even states abroad will have something to learn from such large scale and innovative schemes implemented in individual Indian states.

Perhaps the single largest strength of India as a nation lies in its human resources; it is incumbent upon its policy makers to find effective ways to harness those resources in order to usher the nation into the prosperity that every Indian youth yearns for. Finally, I think it is only appropriate to emphasize here is that the prosperity that education brings is not merely economic prosperity. Education liberates society and creates thinking individuals who tend to have the twin abilities to insulate themselves from dogma and propaganda and at the same time to open themselves up, to give their best to the outer world. The externalities of education are profound and immeasurable. Even today, 40 million children in India work as child laborers, never going to school and having few opportunities to develop. It is the moral responsibility of the government of India, and indeed of each educated person in the nation, to ensure that education reaches those who have been deprived of it. Article 21A of the Indian Constitution embraces the right of children aged between 6 to 14 years to gain free and compulsory education – more than being a legislative statement, this Article encompasses the hopes and aspirations of the founding fathers of the nation and indeed the aspirations of the people of India.

- Data Centre. Accessed November, 2013 http://stats.uis.unesco.org ↑

- “The quality of schooling: Quantity alone is misleading,” American Economic Review 73 (December 1983) ↑