Graphic by Maralmaa Munkh-Achit

Written by Vanessa Otero

Edited by Sonali Uppal

In the United States, the federal government currently does not have much control over what social media companies do concerning the spread of misinformation. The two main laws that apply in this arena—the First Amendment and Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act—fiercely protect social media companies from government action and private liability, leaving it mostly up to the companies to regulate themselves.

Besides misinformation, other problems with social media companies are privacy intrusions and antitrust concerns. To address these issues, legislators have passed laws like the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). Regulators have started creating Federal Communications Commission (FCC) antitrust suits because privacy and antitrust are more manageable issues to solve than misinformation. In this article, ‘misinformation’ broadly refers to content that people consider problematic because it is misleading, false, or damaging to civic discourse. There are many variations of this type of content, and they are problematic to different degrees and audiences. However, most people generally recognize that “misinformation” on social media is damaging in profound and disturbing ways. Another related problem to ‘misinformation’ is ‘polarization.’ Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen how polarized health misinformation has exacerbated the pandemic, resulting in immeasurable sickness and death. And we have seen how polarizing political disinformation culminated in the Capitol attacks of January 6, when rioters used violence to try to overturn the presidential election results. But these significant events are just the most prominent examples. From the ‘Pizzagate’ shootings to the destruction of 5G cellular towers to anti-Asian hate crimes, online polarizing misinformation has been steadily churning out real-life violence and destruction for several years and continues to do so now.

‘What to do about misinformation and polarization’ is a more complex problem to solve than ‘what to do about privacy and antitrust.’ Regulating polarization and misinformation requires legislating social media content moderation itself, which is a problem at two levels—the legal and practical levels.

The Legality of Legislating Content Moderation

At the legal level, legislating content moderation leads to questions about free speech and the First Amendment that are foundational to American democracy. That is, can the government legally regulate the spread of misinformation or polarizing content?

As a general matter, private companies are protected, but not bound, by First Amendment freedom of speech. That is, private companies may restrict speech under their control. However, two factors can nonetheless deter private companies from restricting speech. The first one is ‘freedom of speech,’ which many Americans regard as their ethical and moral right, not merely a constitutional right. As a result, many American companies willingly refrain from restricting controllable speech (such as the speech of their employees). Moreover, companies such as Twitter, Facebook, and Google have publicly cited this ethic of free speech as a virtue to which they are committed as a reason for not restricting speech on their platforms. They are not legally bound to do so under the free speech clause of the First Amendment. But these pronouncements of a dedication to free speech confuse the public, which often misinterprets their dedication to free speech as an ethic as a legal obligation not to suppress their speech. As a result, many laypersons incorrectly interpret the removal of social media posts as an infringement on their legal, indeed First Amendment, rights.

Private companies like social media platforms can moderate speech under the First Amendment as they please, and there are no realistic exceptions that would extend the First Amendment to apply to the platforms. Further, users cannot and will not be able to sue social media companies for infringing on their speech rights.

Whether the government can force social media to moderate content is a different question. In all likelihood, the government could require social media companies to label, limit, or takedown certain content under similar principles that allow the government to require labels on advertisements of products and prohibit false advertising. However, the First Amendment would likely prevent the government from forcing social media companies to remove speech—especially political speech. In other words, social media companies have the power to moderate, and the government has somewhat less power to force moderation.

There are ways the government could regulate social media that are legal under the First Amendment, but they are likely to face political resistance long before they face a potential First Amendment challenge. There is some bipartisan overlap on the idea that ‘social media companies should be regulated on misinformation,’ and many proposals on reforming Section 230. But on the left, the concern is that social media companies need to crack down on misinformation more often. On the right, the concern

is that any content moderation by social media companies results in discrimination against conservatives. The complaint on the right is that ‘big tech’ is ‘silencing’ and ‘censoring’ ‘conservative voices.’ Essentially, conservative legislators such as Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO) and Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) think social media should limit the blocking of content.

Section 230 is in need of significant reform, primarily because the way social media works now is extraordinarily different from how the internet worked when the law was written in 1996.

Section 230 defines an “access software provider” as a provider of software

(including client or server software) or a provider that enables tools that do any one or more of the following:

(A) filter, screen, allow, or disallow content;

(B) pick, choose, analyze, or digest content; or

(C) transmit, receive, display, forward, cache, search, subset, organize, reorganize, or translate content.

Though social media platforms fall under this definition of “access software provider,” the platforms’ technology that exists today is wholly different from the technology that existed when § 1 230 was created. This is one reason why § 230, as it currently exists, is wholly inadequate to address the problems created by how social media distributes content—namely, polarizing content and misinformation—today.

Facebook, Twitter, and Google (particularly via YouTube) algorithms perform far more sophisticated actions beyond the simple ones listed under the definition of “access software provider” in § 230 above. Today, they much more actively direct media content to users to drive higher engagement.

They promote, prioritize, suggest, selectively target, selectively display, and selectively hide content. They also track data related to optimizing viewership and 1 §: section sign engagement. As a result, users who engage with questionable, misleading, problematic, or false content get more of it; users who engage with bias-confirming, polarizing, and extremist content get more of that as well. These engagement optimization algorithms increase the time spent by users on these platforms in furtherance of the platforms’ business models, but the result is that platforms effectively often favor the most polarizing content and misinformation. Reporters have documented and criticized these practices and their effects for years. The recent “Facebook whistleblower” news stories provide new explicit details about these algorithms and what the company knew about their consequences. Such details have caused new levels of public uproar and calls for action. New legislation that reforms or replaces § 230 must account for the technological realities of how much power social media platforms have to amplify misinformation and exacerbate polarization.

New legislation should ideally require more content moderation and remove the lack of liability for platforms for spreading misinformation. However, given the political headwinds and likelihood of pushback from the platforms themselves, Americans should not hold their breath waiting for legislative regulations to stem the tide of misinformation and polarization from social media.

The Practicality of Legislating Content Moderation

Even if the government can legally regulate the spread of misinformation at the practical level, what can it require social media companies to do? That is, what could such laws require that social media companies could realistically implement?

A threshold problem is that social media companies don’t necessarily know how to stop the spread of misinformation, even if they marginally want to. Although these companies generally admit the spread of misinformation is something they should limit or take down from their platforms, the need to limit any content is fundamentally at odds with their primary goals of user engagement and growth. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s 2018 essay on the topic adeptly describes the challenges Facebook faces in this realm, which he succinctly encapsulates in a graphic showing the ‘natural’ engagement pattern for content approaching prohibited content. It shows that the closer the ‘borderline’ content is to prohibited content, the greater its level of engagement.

To the credit of Facebook, Twitter, and other social media companies, they have invested significant time and resources, particularly in AI, to moderate content with a combination of AI and human reviewers. However, certain prohibited content is more straightforward to moderate with these tools than others; violence, pornography, and hate speech are much easier types of content to identify, and subsequently moderate, than misinformation.

So far, Facebook’s efforts consist primarily of using third-party fact-checkers, but public reporting from Columbia Journalism Review indicates that such efforts are limited to a vanishingly small percentage of the content on the platform. Further, fact-checking efforts are necessarily limited to fact-checkable content—that which can be definitively proven false. The same reporting shows that much of this content that is fact-checked and proven false nonetheless gets spread on the platform due to the sheer volume and speed of how content is shared.

There is far more content that is problematic for other reasons, such as that it is ‘merely’ misleading, questionable, incomplete, unverifiable, or suggestive of conspiracy theories—the kind of content that, in Zuckerberg’s graph above, is ‘approaching the line.’ Therefore, fake content that Facebook actively tries to address and ‘borderline’ content that it appears not to address make up a large sea of misinformation.

The vast proliferation of COVID misinformation, election misinformation, and QAnon conspiracy theories illustrates that Facebook’s misinformation moderation problems remain mostly unresolved despite the platform's efforts so far.

The question of polarization is barely acknowledged as a problem by the platforms. Further, the troves of public polling data show startling levels of polarization, and studies on how platform algorithms present different universes of information (i.e., “filter bubbles”) to people based on their political leanings. The platforms didn’t invent political divides, so it is not incumbent upon them to proactively solve them. But they should try to undo the mechanisms that force people into ideological silos and worsen the divides.

There are practical ways that social media companies could significantly reduce their misinformation problems and their exacerbation of polarization. The following proposals are of the type that could be 1) widely accepted by platform users and politicians, 2) permissible under the First Amendment, and 3) helpful.

Create Better Systems for Categorizing Misinformation and Bias

Social media companies need to develop taxonomies and methodologies for categorizing news and news-like content for reliability and bias. Creating a transparent and fair framework for doing so is as important as any governance or regulatory compliance framework the platforms have.

This proposal is no small step. But, arguably, it is the most important one, the most difficult one, and the one the platforms are most resistant to taking on. Both Mark Zuckerberg and Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s CEO, on the topic of misinformation moderation, have stated that their companies shouldn’t be “arbiters of truth.” And for good reason. If they believe their expertise is that of technologists, rather than of truth-arbiters, they are justifiably wary of being responsible for developing such a framework. Facebook recognizes that some need for categorization is necessary, but its existing labels, which it tasks fact-checkers with applying, are limited to “Altered Photo, Missing Context, False Information, or Partly False Information.” These are simplistic and insufficient.

Categorizing information reliability is difficult because truth and falsehood aren’t binary; answering ‘what is true’ is squishy, debatable, and philosophical. However, there are more accurate and less accurate things, and there are real ways to identify them as such. Platforms need to create taxonomies to define what news and news-like information is (likely) good, okay, problematic, and bad.

Further, they should create taxonomies to define left-to-right political slant and bias, differentiating them by degrees. Identifying degrees of ideological bias is crucial because platform algorithms have the effect of creating ideological filter bubbles and that the platforms allow ad targeting by the likely political slant of the user.

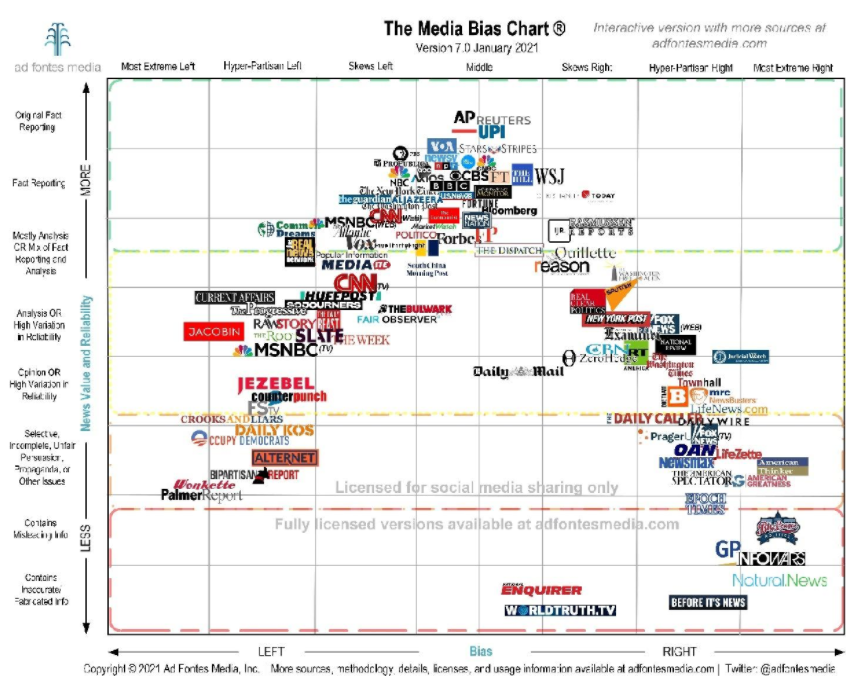

Creating a taxonomy and repeatable methodology for classifying content is challenging to do. My company, Ad Fontes Media, and I have spent five years defining and refining our taxonomies for news source reliability and bias. To the extent the platforms are uncomfortable creating such taxonomies, they should rely on third-party organizations and experts to help them. Ad Fontes provides such taxonomies and methodologies, but there are other organizations doing similar work, which I refer to as “news rating organizations.” Additionally, there are many other individual scholars, researchers, and consultants in fields such as information literacy that the platforms could turn to.

Label Content Internally and Study It

Creating useful taxonomies and transparent methodologies will allow platforms to label content internally and answer important questions informing new policies. Internal policies and proposed legislation often simply guess at what kind of solutions will solve problems without first studying them closely.

Labeling content into distinct taxonomical categories for reliability (e.g., reliable information, opinion, problematic, misleading, false) and left-right spin (e.g., left, right, center, mild to extreme) itself would require large-scale human and AI review. Though it would be practically impossible to label all platform content at first, labeling a sample of the content could provide the platforms valuable insights such as:

What percentage of content is false? What percentage is misleading? What

percentage is problematic? What percentage of false/misleading/problematic content is left-biased vs right-biased? How much more engaging is false/misleading/problematic content than reliable content? Do users who engage with problematic content eventually gravitate to more false or misleading content? What patterns can be discerned among users who share misinformation? What effect does that content have on relationships between users?

Labeling content allows quantification of content types, which in turn can reveal the impact of certain quantities of misinformation impressions on society. For example, such labeling may reveal that less than 1% of platform content is false or misleading, but if between Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube that amounts to a few billion impressions of misinformation in a year, we can see the effects of that amount of content on society. Twitter recently published an internal study showing its platform amplifies right-leaning content more than left-leaning content, using bias classifications from Ad Fontes and others. The study was an important first step for informing further research and internal policy updates and is a perfect example of how content labeling enables meaningful studies.

Provide Useful Information About Content In-Platform

The keyword in this proposal is useful. The useful information must allow for evaluating whether conveyed information is or is not reliable or biased. Facebook has provided information about news sources that is unhelpful in making such assessments. Specifically, it provides little “I” information icons which, when clicked, convey when the linked website was founded and where and how often the linked story had been shared. It tells a user nothing qualitative about the information conveyed.

Platforms can choose to provide many types of information overlaid or adjacent to content—such displays are known as “interstitials.” For example, they could provide information from vetted third parties (i.e., from fact-checkers, news rating organizations, individual experts). Alternatively, they could go as far as to label content publicly in the

same way they label it internally. This labeling could require an ‘opt-in’ from users, because not all users may want such labels.

News rating organizations often analogize information labeling to nutrition labeling. Content ratings already exist for movies, TV, and video games. Such labels don’t prevent anyone from consuming the product or content—they don’t limit speech—but they helpfully orient consumers about what they are about to encounter. Many users would find such labels (reputable/opinion/problematic/misleading/false & left/center/right) useful and would opt-in to them.

Provide Users Choice About Algorithmic Presentation of Content

In addition to providing users with the option to see content labels, users should be made aware of how algorithms present particular types of content over time and provide them with options to control it.

To ensure effectiveness, such options should be prominent, easy to understand, and easy to select. Platforms currently have limited explanations and options for ‘controlling’ one’s feed, but they are about as useful to most users as the fine print in a mortgage contract. Just as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau now requires the most important terms in a mortgage that affect a borrower’s rights to be presented in large print much more prominently, social media platforms should present salient information to their users better.

First, platforms should periodically provide usage statistics to users about the content they consume. For example, platforms could provide statistics such as ‘12% of the content you engaged with this week had reliability ratings of ‘problematic’ or ‘misleading,’ or ‘87% of the news content you engaged with was rated left politically.’

Equipped with such insights, users might choose to control their feeds further if given additional control about how political content and labeled misinformation are shown to them.

Platforms should provide options to users to do one or more of the following:

1) Not show them content labeled as misinformation (or at least label it)

2) Show them a purposely balanced feed to break their echo chambers

3) Show them an opposite viewpoint political feed for a certain time period

4) Not show them any political news

5) Not use their engagement patterns to recommend or prioritize news and information content

For many users, simply knowing how algorithms push polarizing content and misinformation now would be a revelation; allowing them more control over the algorithmic levers would allow them to break harmful information cycles themselves.

Regulations for Better Information and More Consumer Choice vs. Regulations for Content Moderation Itself

The practical steps outlined herein are the type that social media companies could implement on their own. They are suggestions for providing more and better information to consumers and for allowing them a choice. Both consumers and the platforms themselves should find this more palatable than mandates to moderate content because it avoids having companies make ultimate decisions about speech.

Most consumers are wary of limitations on speech, but so many are hungry for just a little help from the platforms and their governments. They want some protection from being duped and further divided. It’s the least both social media and the government can do.