By Yiming Zhong

Edited by Muhammad Hani Ahsan

Graphic by Norie Wright

#Science and Technology #Economic

“The first sound that Yaroslav Vinokurov, 24, heard in the early morning was the wailing of the air-raid alarm in the darkness and he continued his work, given that alarms sound nearly every day. But soon machine-gun fire echoed through the Shevchenkivskyi district as air-defense systems flashed in the sky, followed by what he described as “a very loud explosion.” “I lay down on the floor, as I didn’t know what else can happen,” Mr. Vinokurov said. Many buildings were damaged and some of the transportation mobiles were destroyed by the attack.”1 This was reported by the New York Times on December 14, 2022.

Drones have emerged as an effective weapon in the 21st century. Most modern militaries deploy drones for a range of purposes including surveillance and precision strikes. However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has opened a new chapter in the use of drones in military combat. The Russian army is deploying Iranian-made Shahed-136 drones to conduct kamikaze attacks on Ukrainian military facilities.2 Increasingly, drones have also been used by Russian forces to target civilians and civilian infrastructure including transport.3 Drones are capable of seeking out and destroying specific targets, spreading terror, and weakening the resolve of soldiers and civilians.4 Due to their success as precision weapons, drones are potent, difficult-to-stop, and cost-effective. The Russian drone offensive in Ukraine is unique because of the deployment of civilian drone technology for military purposes.

The growth of the civilian drone market, the difficulty in controlling the proliferation of civilian drone technology for military purposes, and the cost-effectiveness of civilian drones pose critical risks for geopolitical stability and national security.

Figure 1 — A drone approaching for an attack in Kyiv5

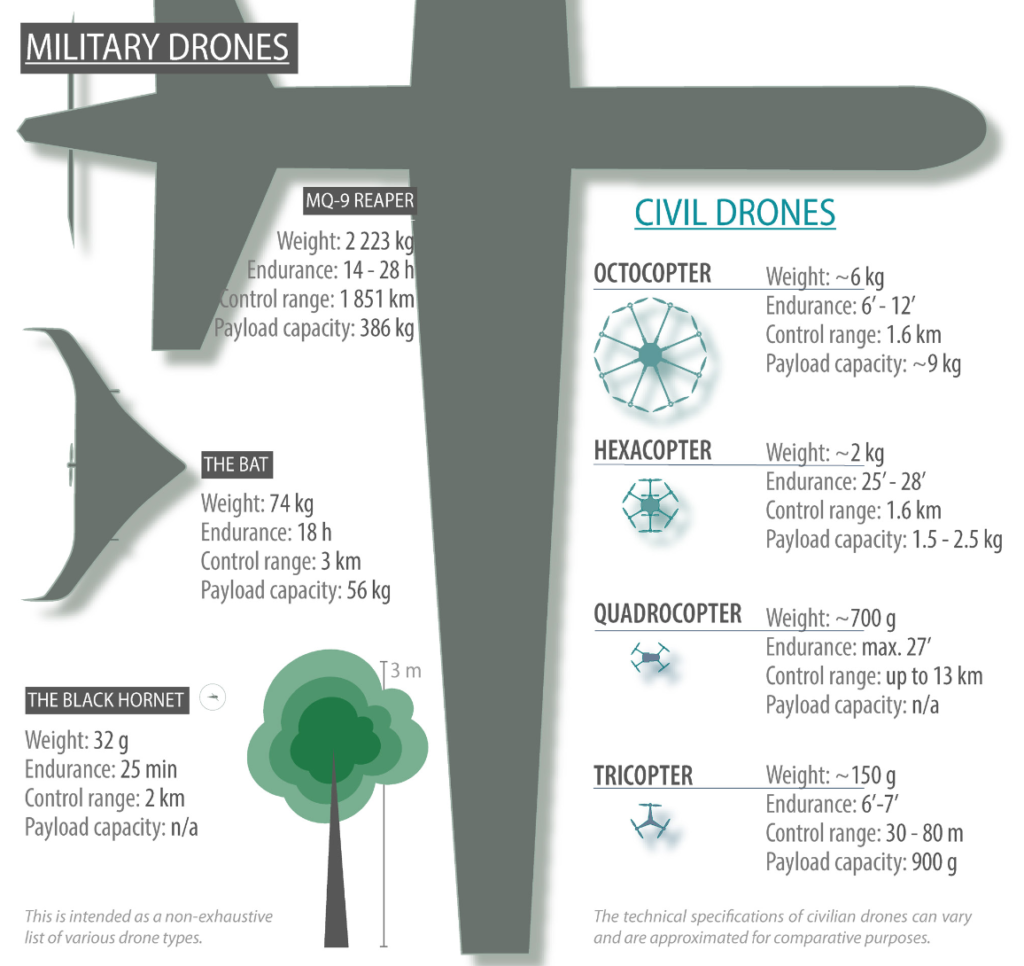

Military Drones vs Civilian Drones

An unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), or drone, is an aircraft that operates remotely or autonomously through a sophisticated GCS Unit.6 Drones do not carry onboard operators and rely on wireless remote controls or programmed instructions. Some UAVs are deployed on one-time missions while others are reusable. Drones can carry both lethal and non-lethal payloads. The difference between military drones and civilian drones lies in their design and performance. Military drones are designed for military purposes with higher performance requirements. Civilian drones are designed for civilian applications with a focus on comfort and portability.

Military drones are designed for military purposes, such as reconnaissance, target strikes, and intelligence gathering. They specifically have stronger structures and higher durability to withstand harsh battlefield environments. Civilian drones are typically designed for consumer or industrial use with a focus on comfort and portability. Civilian drones are useful for aerial photography, cargo transportation, and agricultural spraying. Military drones generally have higher performance requirements, such as longer endurance, higher speed, and a longer communication range. The unmanned military aircraft also carry powerful sensors and weapon systems due to the higher demands of military missions. The performance of civilian drones varies depending on the specific application and market demand.7

It is worth noting that with the continuous development and application of drone technology, the boundary between military drones and civilian drones may become blurred. Some drones may have applications in both the military and civilian fields. Reconnaissance can be a military function of drones but it may also be a function of civilian drones. However, a worrying trend is the use of civilian drone technology for military purposes. In the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine, all sides have reportedly used modified civilian drones for military purposes. Many also observed a ‘significant growth’ in the combat use of civilian drones in Yemen, Syria, and Iraq. On the other hand, military drones have also been used for civilian purposes.8 In the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey in 2017, the U.S. military deployed military drones to assist in search and rescue operations.10

Figure 2 – Examples of various of civil and military drone models11

The Origin and Use of Drones

In 1927, A.M. Low, the “Father of the Remotely Piloted Vehicle”, successfully tested the unmanned aircraft he developed on the British warship “Fortress.”12 Britain successfully developed an unmanned target drone, the “Fairey Queen”, in 1931 and used it in naval fleet exercises. In the mid-1950s, the United States launched the first practical reconnaissance aircraft in its history: the AN/USD-1 unmanned reconnaissance aircraft.13 The U.S. U-2 unmanned reconnaissance aircraft, Ryan Model 147, and other military drones appeared during the Vietnam War. Early U.S. drone technology was used to counter the threat posed by the Soviet Union through intelligence gathering.14 The Israeli military’s surprise attack on the Syrian Army in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley in 1982 was an early demonstration of the impact that drones have in combat. During the Gulf War, the U.S. military deployed Predator drones armed with Hellfire missiles to carry out targeted strikes against the Iraqi government and military targets.15 Drones became a multifunctional combat aircraft integrating “reconnaissance and strike” capabilities in the war in Afghanistan in 2001.”16 The U.S. military’s predator drones launched hellfire missiles at specific targets. In 2015, Houthi rebels used Iranian drones to attack the American armed Saudi military.17 The civil war in Yemen is the first major instance of nonstate actors using drones for combat. Drones also made a difference in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh (Azerbaijan-Armenia) war. Azerbaijan’s use of armed drones, including kamikaze drones, was a major advantage in the field, leading to a political victory facilitated by Russian mediation.18 The trend in military history and recent conflicts provide evidence that the future of war entails the use of unmanned vehicles and artificial intelligence.

Advantages of Drones

Drones have characteristics that make their use for military purposes highly advantageous for armies and non-state actors. War drones have two unique advantages. First, unlike aircraft or raids, drones are unmanned and fly directly over hostile territories to identify targets. Using drones limits the risk of personal injury, capture, or death on the attacking side.19 Second, drones provide a near-instantaneous response, dramatically shrinking the “find-fix-finish” loop.20 The development of drone technology widens the military-technology gap between rich and poor countries. The United States, China, and Israel monopolize the market for drones with advanced and robust products. As a result, these countries can advance their strategic interests and assert military hegemony. However, other countries, such as Iran and Russia, have also entered the market for drones, laying the groundwork for an arms race over drone technology.

Economic Factors

The growth of the civilian drone market may lead to the proliferation of drones for military purposes. According to Expert Market Research, the global military drone market is expected to reach $22.4 billion by 2024.21 The United States has spent approximately 0.4% of its defense budget on drone systems in recent years, with a projected budget of $3.1 billion in 2023.22 There are few countries with the capability to independently produce high-performance military drones leading to monopolization of the market. According to SIPRI statistics, Israel, the United States, and China accounted for 31%, 28%, and 17% of the export share respectively from 2010-2020. China, although starting later, has rapidly developed its military drone capabilities with drones such as the “Wing Loong” and “Rainbow.”

However, the market for civilian drones is larger than the market for military drones, and their potential military use can lead to unprecedented and uncontrollable outcomes. Frost & Sullivan’s forecast, the Global Commercial UAS Market Outlook, 2020, predicts that the drone industry is transitioning from a nascent to a growth stage.23 Due to a surge in demand for commercial drones, unit shipments are estimated to rise at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.5%. There will be 2.91 million units by 2023 compared to 2.44 million units in 2019.24

Consumer drones have dominated the civilian drone market in recent years. But with the expansion of industrial applications, the market size of industrial drones is expected to grow rapidly. Shenzhen UAV Industry Association announced that the global civilian drone market will grow to 59.38 billion USD (415.72 billion RMB) by 2024.25 These figures reflect a compound annual growth rate of 43.03% from 2015 to 2024. But the market value of industrial drones will reach 45.83 billion USD (320.82 billion RMB) by 2024, accounting for approximately 77% of the global civilian drone market. Thus, the market for industrial drones has an average annual compound growth rate of 57.55% from 2015 to 2024.26

Military Embargoes

The components required to manufacture drones are difficult to embargo. Countries that face military sanctions can take advantage of civilian drone technology to develop a fleet of “military drones.” This makes it challenging to regulate the proliferation of drones, especially in conflict zones or areas with limited governance. Iran has been using civilian technology to reduce the cost of producing military drones. Most military drones are made from aerospace aluminum alloy, fiberglass, or high-strength plastic.27 Iran also relies on purchasing commercial satellite communication services for its military drones.28 These components and communication services are intended for civilian purposes and are difficult to embargo, enabling Iran to develop and export military drones. Countries presently lagging behind in the arms race for drone technology may begin to catch up by using civilian drones to support military operations.

Drones can also be used for illicit activities such as smuggling, espionage, and drug trafficking. The lack of regulation on the buying and selling of civilian drone technology may enable terrorist groups and other non-state actors to acquire drones for military purposes. Drones are already being deployed by non-state actors. During the Libyan Civil War, the LNA attacked the internationally recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) using drones.29 The success of the drone strikes led to the Turkish military’s intervention to prevent the collapse of the GNA.30 The rapid development of drone technology and the unregulated conversion of civilian drones for military use are expected to grow posing major risks for national security and geopolitical stability.

The Calculus of Waging Warfare

Carl von Clausewitz’s theory of war states that war is the continuation of political intercourse through other means.31 The theory can be applied to the use of drones in warfare as well. What political objectives are to be achieved through drone wars? Drones can be useful for capturing territories as the case of the Nagonorna-Karabakh conflict demonstrates. Drones are also being deployed by nonstate actors to challenge the government in the Yemen and Lebanon.

Drones built using civilian drone technology are vulnerable to defense systems such as electromagnetic interference systems and high-intensity air defense. Yet, civilian drones are cost-effective and can compensate for reconnaissance shortcomings. One analysis suggests that it only cost Russia between $12 to $18 million to launch a wave of drone attacks, but it cost Ukraine $28 million to defend against Russian drone strikes.32 Russia has an advantage in the invasion since it is cheaper for Russia to manufacture drones and costlier for Ukraine to neutralize the drones.33 The Shahed-136 drones deployed by Russia are also relatively inexpensive to produce with an estimated cost of $20,000. But the cost of destroying the Shahed-136 drone can range from $140,000 to $500,000.34 These figures do not consider the costs when drones hit their targets, damaging military equipment and critical infrastructure. Drones are also cost-effective compared to traditional air raids.The U.S. bombing campaign over North Vietnam from 1965-1966 cost $6.6 to $9.6 for one dollar of damage.35 The cost-effectiveness of converting low-cost civilian drones for military purposes and their potential in combat makes it likely that the use of drones in combat will grow.

Non-state actors, such as Houthi militants in Yemen, indicate a different cost and damage ratio. Houthi rebels deployed civilian drones that could travel a range of 930 miles to attack Saudi Arabian military targets and infrastructure. The drones used may have cost $15,000 or less to build but have had a profound impact on the conflict.36 According to the CSIS’s report, using drones to attack Saudi infrastructure was a cost-effective way to inflict maximum economic and reputational consequences on the Saudi government.37 Patriot interceptors bought from the United States to intercept drones can cost over $1 million. The Houthi UAVs may cost only a few hundred dollars in comparison.38

Unprecedented Possibilities

The conversion of civilian drones for military purposes presents unprecedented possibilities that pose critical risks for national security. Non-state actors may begin using civilian drones for military purposes to inflict damage to the economy, infrastructure, and military facilities, and spread terror among the population. Terrorist groups may also use civilian drones to conduct terrorist attacks including kamikaze bombings. Beyond non-state actors, countries that are presently lagging behind in drone technology may acquire advanced precision strike and intelligence gathering capabilities . We may also see the use of drones in regional and local conflicts leading to risks of casualties and economic damage.

Conclusion

The use of civilian drones in the military has the potential to significantly impact the geopolitical landscape and raise security concerns. The growth of the civilian drone market increases the affordability and accessibility of drone technology, resulting in widespread proliferation. Drones are difficult to sanction and embargo, posing challenges for international regulation. The “find-fix-finish” capability of drones, which refers to their ability to locate, track, and strike targets, can create uneven power dynamics in conflicts. Lastly, the proliferation of civilian drones in military use by non-state actors, such as rebel groups and terrorist organizations, adds another layer of complexity to the future of drones in warfare.

1. Santora, Marc, and Andrew E. Kramer. “Russia-Ukraine War: Ukraine Air Defenses Shoot Down Russian Drones, but Kyiv Sustains Damage.” The New York Times, December 14, 2022, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/live/2022/12/14/world/russia-ukraine-news.

2. Trita Parsi, “Last Chance for America and Iran: A New Nuclear Deal Won’t Survive Without a Broader Rapprochement,” Foreign Affairs, August 26, 2022, https://perma.cc/M7SG-96ST; see also Robinson, “What Is the Iran Nuclear Deal?”; and Patrick Wintour and Jennifer Rankin, “Iran Breaching Nuclear Deal by Providing Russia With Armed Drones, Says UK,” The Guardian, October 17, 2022, https://perma.cc/2FBZ -UJZ8.

3. Newdick, Thomas. “Russia Bombards Ukraine With Iranian ‘Kamikaze Drones.’” The Drive, October 17, 2022. https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/russia-bombards-ukraine-with-iranian-kamikaze-drones.

4. PBS NewsHour. “How Russia Is Using Iranian Killer Drones to Spread Terror in Ukraine,” October 17, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/how-russia-is-using-iranian-killer-drones-to-spread-terror-in-ukraine.

5. Talley, Ian, and Benoit Faucon. “U.S., Europe Struggle to Keep Iran’s Drones From Russian Military.” Wall Street Journal, October 20, 2022, sec. World. https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-europe-struggle-to-keep-irans-drones-from-russian-military-11666263602.

6. Aero Sentinel. “What Are Military Drones? Aero Sentinel Artical.” Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.aero-sentinel.com/military-drones-article/.

7. Tania, LATICI. “Civil and Military Drones, Navigating a Disruptive and Dynamic Technological Ecosystem,” 2019. The European Parliament.

8. “Humanitarian Concerns Raised by the Use of Armed Drones – World | ReliefWeb,” November 6, 2020. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/humanitarian-concerns-raised-use-armed-drones.

9. ibid

10. Joint Base San Antonio. “Army South Soldier Uses Drone to Assist in Hurricane Harvey Relief Efforts.” Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.jbsa.mil/News/News/Article/1305699/army-south-soldier-uses-drone-to-assist-in-hurricane-harvey-relief-efforts/https%3A%2F%2Fwww.jbsa.mil%2FNews%2FNews%2FArticle%2F1305699%2Farmy-south-soldier-uses-drone-to-assist-in-hurricane-harvey-relief-efforts%2F.

11. Tania, LATICI. “Civil and Military Drones,” October 2019. European Parliamentary Research Service.

12. Larm, Dennis. “Introduction.” Expendable Remotely Piloted Vehicles for Strategic Offensive Airpower Roles. Air University Press, 1996. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep13923.7.

13. Boring, War Is. “The U.S. Army Got Its First Drones 55 Years Ago.” War Is Boring (blog), July 28, 2014. https://medium.com/war-is-boring/the-u-s-army-got-its-first-drones-55-years-ago-fc92ca1c3b3d.

14. Larm, Dennis. “Expendable Remotely Piloted Vehicles for Strategic Offensive Airpower Roles,” June, 1996. Air University Press, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama.

15. From Balloons to Drones. “First Gulf War,” October 19, 2022. https://balloonstodrones.com/tag/first-gulf-war/.

16. Office of the Secretery of Defense. 2005. Unmanned Aircraft Systems Roadmap 2005-2030.

17. DENNIS M. GORMLEY. “Chapter 12. New Developments in Unmanned Air Vehicles and Land-Attack Cruise Missiles | SIPRI.” Accessed April 13, 2023. https://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2003/12.

18. Military Strategy Magazine. “Drones in the Nagorno-Karabakh War: Analyzing the Data.” Accessed April 17, 2023. https://www.militarystrategymagazine.com/article/drones-in-the-nagorno-karabakh-war-analyzing-the-data/.

19. Micah Zenko. Jan., 2013. Council on Foreign Relations. Reforming US Drone Strike Policies. Council Special Report No.65

20. ibid

21. “Market Research Reports | Strong Industry Analysis | Expert Market Research.” Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.expertmarketresearch.com/about-us.

22. Office of the under Security of Defense (COMPTROLLER)/Chief Financial Officer. April 2022. Defense Budget Overview. United States Department of Defense Fiscal Year 2023 Budget Request.

23. Valente, Francesca. “Commercial Drone Market to Hit 2.91 Million Units by 2023, Says Frost & Sullivan.” Frost & Sullivan (blog), April 8, 2020.

25. Shen Zhen UAV Industry Association, UAV Industry Report “「无人机」行业研究报告_深圳市无人机行业协会.” Accessed April 13, 2023. http://www.szuavia.org/news_cen.php?cid=25&id=6583.

26. ibid

27. Hui Zhang; Minghui Shan; Zhe Dong. People’s Liberation Army Daily. The Rise of Iranian Military Used Drones“伊朗军用无人机异军突起 ‘空中波斯弯刀’或将四两拨千斤 – 中国军网.” Accessed April 17, 2023. http://www.81.cn/wj_208604/jdt_208605/10204835.html.

28. ibid

29. Gatopoulos, Alex. “‘Largest Drone War in the World’: How Airpower Saved Tripoli.” Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/5/28/largest-drone-war-in-the-world-how-airpower-saved-tripoli.

30. ibid

31. Clausewitz, Carl von. 1997. On War. Translated by J. J. Graham. Wordsworth Classics of World Literature. Ware, England: Wordsworth Editions.

32. Boffey, Daniel. “Financial Toll on Ukraine of Downing Drones ‘Vastly Exceeds Russian Costs.’” The Guardian, October 19, 2022, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/oct/19/financial-toll-ukraine-downing-drones-vastly-exceeds-russia-costs.

33. Bigg, Matthew Mpoke. “Ukraine Keeps Downing Russian Drones, but Price Tag Is High.” The New York Times, January 4, 2023, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/03/world/europe/ukraine-russia-drones.html.

34. ibid

35. Lewy Guenter. 1980. America in Vietnam (a Galaxy Book ; Gb 601). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195027329.

36. Hubbard, Ben, Palko Karasz, and Stanley Reed. “Two Major Saudi Oil Installations Hit by Drone Strike, and U.S. Blames Iran.” The New York Times, September 14, 2019, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/14/world/middleeast/saudi-arabia-refineries-drone-attack.html.

37. Jones, Seth G., Jared Thompson, Danielle Ngo, Joseph S. Bermudez Jr, and Brian McSorley. “The Iranian and Houthi War against Saudi Arabia,” December 21, 2021. https://www.csis.org/analysis/iranian-and-houthi-war-against-saudi-arabia.

38. Lubold, “Saudi Arabia Pleads for Missile-Defense Resupply as Its Arsenal Runs Low.”