By: Mira DeGregory

Edited By: Alejandro Ramos

Introduction

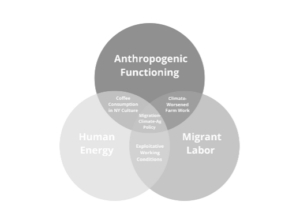

Every morning, millions of New Yorkers sip their lattes, unaware of the complex network of agricultural, immigration, and climate systems that make this ritual possible. The seemingly simple act of drinking coffee masks a global supply chain reliant on Costa Rican coffee and New York dairy. These ingredients depend on immigrant labor, ecosystems increasingly strained by climate change, and policies that fail to address the inequities and vulnerabilities within this nexus. To sustain this interconnected system, New York must adopt equitable and sustainable policies that protect both the environment and the laborers who sustain it.

The Energy Exchange Behind a Latte

The production of a latte’s core ingredients—coffee and dairy—relies on intensive human labor and ecosystems vulnerable to climate change. In New York, dairy farms produce 15.7 billion pounds of milk annually,1 supported by a workforce where 51% of workers are immigrants,2 primarily from Mexico and Guatemala.3 Many of these workers, often undocumented, face systemic vulnerabilities such as exclusion from labor protections and substandard housing.

In Costa Rica, coffee—hand-picked, dried, and processed by peons––relies on a migrant workforce,4 75% of whom are Nicaraguan and Ngäbe-Buglé Indigenous peoples from Panama.5 These laborers endure physically grueling tasks and harsh conditions for minimal wages, often earning as little as USD 60 a day. This system underscores the inextricable link between human energy and agricultural production across borders.

Photo by Mira DeGregory

Labor Dynamics in Coffee and Dairy Production

Farm labor in both industries demands immense physical effort. Costa Rican coffee pickers harvest up to 200 pounds of coffee cherries daily by hand, bending and lifting under the sun on uneven terrain.6 In New York, dairy workers milk cows, clean barns, and handle livestock, often working sixty to eighty hours per week.7 In both industries, physically taxing work leads to chronic fatigue, musculoskeletal injuries, and mental strain8 and is further enabled by insufficient health insurance9 options, lack of transportation, and high out-of-pocket costs for migrant farm workers.

Climate Impacts

Climate change is set to exacerbate the harsh conditions for farm laborers in the U.S. and Costa Rica. In upstate New York, dairy workers will face more frequent heat waves and rising humidity levels, increasing the risk of heat-related illnesses.10 Tasks like cleaning barns and handling livestock will become more hazardous as extreme weather events compromise barn ventilation and worker safety. In Costa Rica, coffee farmers will confront rising temperatures and unpredictable rainfall, leading to prolonged harvest seasons, landslides, and the spread of pests like the coffee berry borer.11 These shifts will demand more hours in the field under hotter, more dangerous conditions. For both industries, climate change intensifies an already arduous work environment, further endangering the health and well-being of farmworkers vital to global food and beverage supply chains.

There is an inextricable link between human energy, migrant labor in New York and Costa Rica, and how New Yorkers function in an anthropogenic world. To sustain this system, we need solutions that build resilience across all parts of this nexus, including political protections for migrant workers through immigration reforms and climate resilience laws.

New York must secure justice for the laborers who make it possible to continue enjoying the benefits of coffee.

Policy Analysis: Costa Rican Framework for New York State

New York’s policy landscape demonstrates progress but falls short compared to Costa Rica’s comprehensive approach. The Farm Labor Fair Labor Practices Act (FLFLPA)12 provides rights to farm workers except for undocumented workers, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation and without organizing and collective bargaining rights. Similarly, the federal Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act (MSPA)13 offers baseline protections for workers but lacks robust enforcement, perpetuating unsafe working conditions. Systems like the New York State Migrant Education Program (NYS-MEP)14 provide crucial educational resources for the children of migrant workers but fail to address systemic inequities faced by adult laborers. On the climate adaptation front, New York’s dairy farms remain significant contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, mainly methane. Cornell Cooperative Extension’s experimental Payment for Environmental Services (PES)15 models could incentivize climate-conscious production and mitigate NY’s footprint. However, PES modeling is in the preliminary stages in New York and will not be scaled to the dairy industry without a successful pilot. These gaps reflect an absence of interconnectedness between policies; labor protections, education programs, and sustainability efforts operate in silos rather than synthesizing. Bridging these gaps requires a holistic framework considering how the nexus of labor, human energy, and anthropogenic policies can be mutually reinforcing.

Costa Rica exemplifies an innovative and integrated framework for addressing this nexus. The approach is summarized in the following table.

Together, these policies create a web of resilience and strengthen all facets of the labor-energy nexus by integrating migration systems, sustainable environmental incentives, and climate-adapted agricultural practices. This interconnected approach prioritizes ecological sustainability and social equity, providing a model for holistic policy development in New York.

Recommendations for New York

To strengthen its migration-climate-agriculture nexus, New York State government can adopt the following measures:

-

-

- Implement a system like SITLAM to regularize undocumented workers.

- Facilitate a PES pilot to be expanded across New York State with integrated CSA practices.

- Advocate for federal bilateral labor agreements to formalize migration pathways for Mexican and Guatemalan workers in-state.

- Establish heritage acknowledgment and mobility provisions for individuals with H2-A visas traversing from the U.S-Mexico Border to New York State.

-

Conclusion

A latte isn’t just caffeine and milk—it’s an energy exchange that connects the labor of immigrant workers to the energy New Yorkers rely on daily. But this exchange is imbalanced, with the hands that fuel the system exploited and unsupported. New York cannot continue to consume this energy without reinvesting in the human capital that sustains it. By adopting policies that protect migrant workers and promoting climate-smart agriculture along the nexus, New York can build a resilient system where energy is exchanged in a just, sustainable, and shared manner.

Works Cited

1. New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets. Rep. 2022. New York State Dairy Statistics Report. https://agriculture.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2023/09/2022dairystatisticsannualsummary.pdf

2. National Milk Producers Federation. 2022. “Agriculture Labor & Immigration Reform: American Dairy Farms & NMPF.” March 10. https://www.nmpf.org/issues/labor-rural-policy/labor-and-immigration-reform-efforts/

3. Hill, Michael. 2022. “Farmers Alarmed as NY Looks at Expanded Overtime for Workers.” AP News, January 28. https://apnews.com/article/kathy-hochul-business-new-york-united-states-race-and-ethnicity-9b79be48837b8df7a4ec6f829eb3b6a8

4. Hodel, Steven. 2023. “Costa Rica Coffee Pickers: A Day in the Life.” The Tico Times, August 18. https://ticotimes.net/2020/09/21/costa-rica-coffee-pickers-a-day-in-the-life

5. Murillo, Álvaro. 2024. “Costa Rica Guarantees Fair Compensation and Benefits for Coffee Pickers.” El País, February 10. https://english.elpais.com/international/2024-02-11/costa-rica-guarantees-fair-compensation-and-benefits-for-coffee-pickers.html.

6. Hodel, Steven. 2023. “Costa Rica Coffee Pickers: A Day in the Life.”

7. Hill, Michael. 2022. “Farmers Alarmed as NY Looks at Expanded Overtime for Workers.”

8. Arcury, Thomas, and Sara Quandt. 1998. “Occupational and Environmental Health Risks in Farm Labor.” Human Organization 57, no. 3. September. 331–34. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.57.3.m77667m3j2136178

9. Voorend, Koen, and Daniel Alvarado. 2022. “Barriers to Healthcare Access for Immigrants in Costa Rica and Uruguay.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 24, no. 2. June 24. 747–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-022-00972-z.

10. USDA. 2024. “Weather and Climate Considerations for Dairy.”

11. Errico, Gina. 2023. “‘It Breaks My Heart’: Costa Rica’s Coffee Communities Challenged by Climate Change.” Yale Climate Connections. https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2023/04/it-breaks-my-heart-costa-ricas-coffee-communities-challenged-by-climate-change/

12. New York Public Employment Relations Board. 2024. “Guide to Understanding the Farm Laborers’ Fair Labor Practices Act.” https://perb.ny.gov/initial-guide-collective-bargaining-rights-and-responsibilities-under-farm-laborers-fair-labor

13. DOL. 2024. “Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act (MSPA).” https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/agriculture/mspa

14. New York State Migrant Education Program. 2024. “About.” https://www.nysmigrant.org/about.

15. Cornell Cooperative Extension. 2024. “Payment for Ecosystem Services.” https://ccetompkins.org/agriculture/payment-for-ecosystem-services

16. IOM. 2024. “Regularization Fact Sheet.” Costa Rica: IOM UN Migration. January. https://costarica.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1016/files/documents/2024-02/regularization-factsheet-1-feb.pdf

17. UNFCC. 2024. “Payments for Environmental Services Program | Costa Rica.” https://unfccc.int/climate-action/momentum-for-change/financing-for-climate-friendly-investment/payments-for-environmental-services-program

18. IAEA. 2017. “Costa Rica Paves the Way for Climate-Smart Agriculture.” December 7. https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/costa-rica-paves-the-way-for-climate-smart-agriculture

19. IOM. 2022. “Key Government Officials from Five Countries Participated in a Regional Exchange on the Implementation of Bilateral Labour Migration Programs.” Western Hemisphere Program, January 6. https://programamesoamerica.iom.int/en/SITLAM-exchange-CostaRica

20. Mora, Maria Jesus, Ariel Riuz Soto, and Andrew Selee. 2024. “Building on Regular Pathways to Address Migration Pressures in the Americas.” Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/mpi-iom_regular-pathways-americas-2024-final.pdf